One of my personal “Great Moments in Family History Research” occurred several years ago in the town hall of Pomfret, Connecticut. I was immersed in a volume of early Pomfret land records at a small table set aside for researchers, when I happened to ask a former town clerk in passing whether any of the town’s early tax lists had survived. Without a word, she disappeared into the town hall’s records vault and emerged carrying a large cardboard box filled with original copies of eighteenth-century local tax lists.

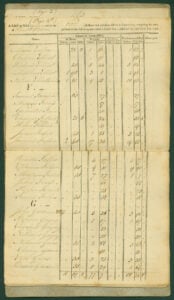

I hadn’t really worked with tax lists before, but I knew that they were supposed to be a useful source of information for family history research. From an early date, American towns large and small annually assessed the value of their residents’ property holdings for tax purposes. Each year, a detailed tax list – commonly known in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries as an “assessment list,” “assessment roll,” “rate list,” or “rate book,” depending on the time and place – was compiled by town authorities (known as “listers” in Connecticut) listing the name of every local property owner and the amount of taxes that he or she owed. During the nineteenth century, these lists often included detailed information about the property on which the tax-payer’s assessment was based, including the amount of land owned, its appraised value, the appraised value of the tax-payer’s house and material possessions, and more. Because the vast majority of pre-twentieth-century Americans farmed for a livelihood, many tax lists also delineated the specific amounts of “plow-land,” pasture, meadow, and woodland that each local tax-payer owned, along with the quantities and varieties of livestock owned.

I had regularly used local land records to identify the location and size of an ancestor’s landholdings, but the tax lists allowed me to go further...

The Pomfret tax lists proved to be a treasure trove. I had regularly used local land records to identify the location and size of an ancestor’s landholdings, but the tax lists allowed me to go further – making it possible for me to compare the size and value of my ancestors’ property holdings with those of other residents in the community. By carefully rank-ordering the taxable wealth of every local property-owner identified on a Pomfret tax list for a given year, I was able to measure the economic status of three generations of my eighteenth-century ancestors relative to that of the town’s other property owners. And because wealth and property largely determined social status in pre-twentieth-century America, the lists were helpful in identifying my ancestors’ position in local society as well.

Tax lists aren’t always easy to find. Some – such as those in Pomfret – are still stored in the local town hall, while others have been transferred to the local or county historical society. And some may have found their way into the collections of the state library, state archive, or state historical society. No matter how scattered they may prove to be, however, a search for them is well worth while – and perhaps essential for determining where an ancestor’s family ranked within the social and economic hierarchies of its community.[1]

Note

[1] After 1900, as U.S. society became increasingly urban and the populations of U.S. cities swelled in size, local tax lists grew so large and unwieldy that they became impracticable for research on twentieth-century families.

Share this:

About Michael Grow

Michael Grow, a retired history professor at Ohio University and a longtime NEHGS member, is the author of John Grow of Ipswich, Massachusetts and Some of His Descendants: A Middle-Class Family in Social and Economic Context From the 17th Century to the Present (Amherst, Mass.: Genealogy House, 2020).View all posts by Michael Grow →