Those of us who love the informalities and irregularities of older cemeteries know that there are surprises and delights at every turn. On our rambles (mine, at least), progress is slow as we meander, waylaid and stopped in our tracks by the transcendent folksy beauty of carvings; by messages of remembrance, love, and loss; by wisdoms, life philosophies, and, occasionally, a mischievous bit of humor that momentarily lifts us from our solemnity.

Those of us who love the informalities and irregularities of older cemeteries know that there are surprises and delights at every turn. On our rambles (mine, at least), progress is slow as we meander, waylaid and stopped in our tracks by the transcendent folksy beauty of carvings; by messages of remembrance, love, and loss; by wisdoms, life philosophies, and, occasionally, a mischievous bit of humor that momentarily lifts us from our solemnity.

In the older cemeteries, even when we’ve seen the classic motifs a hundred times before, or feasted on the opulence of Victorian-era monuments, there is always another example that seems to swallow our attention from a distance. We make a beeline to it, certain that it is the headstone of all headstones, the pièce de résistance, only to have another one come along that sets the bar even higher.

Absorbed in admiration for the face value of old stones, or any unusual headstone for that matter, it is sometimes easy to forget that a human story is buried beneath each and every one, a story that may be hinted at by the inscription but is never sufficiently told. Such was the case recently when, during a stroll in the Hingham Cemetery, whose lovely Recording Angel was the subject of a Vita Brevis post in 2018, my son contemplated the inscription on a grave whose headstone – a handsomely sculpted, playful bronze seal decorated with starfish – commemorates “Beloved Adventurers,” a couple who died on the same day in 1988, one of the newer graves in the ancient burying ground.

My son wondered aloud what the circumstances of their passing might have been. The genealogist in me will always set myself the task of learning more and, indeed, once we returned home, I researched the grave. The casual passerby, however, is left with the unanswered questions. If only a QR code or some sort of information chip could tell a fuller story: a service, maybe, that funeral homes might consider adding to their merchandise packages.

If only a QR code or some sort of information chip could tell a fuller story: a service, maybe, that funeral homes might consider adding to their merchandise packages.

Established ca. 1672, the Hingham Cemetery has no shortage of surprises and buried stories, but for me one marble headstone stands out from all the others. It is not a particularly opulent or large headstone by Victorian standards, but its inscription is remarkable, a harrowing roadmap through one of America’s darkest chapters. The headstone marks the grave of Peter Ourish – Hingham’s youngest volunteer – who fought in fifteen bloody battles during the human catastrophe that was the Civil War.

The son of German immigrants, Peter was born in Buffalo, New York on 15 April 1845. By 1850, the family is enumerated on the census for Hingham. Peter was the third child and second son of Simon Ourish, a yeoman who died of consumption 9 February 1856, and Agnes Hoser, who died in December 1864. Their family home was located on a three-acre parcel at the corner of Lincoln Street and Crow Point Lane.

The son of German immigrants, Peter was born in Buffalo, New York on 15 April 1845. By 1850, the family is enumerated on the census for Hingham. Peter was the third child and second son of Simon Ourish, a yeoman who died of consumption 9 February 1856, and Agnes Hoser, who died in December 1864. Their family home was located on a three-acre parcel at the corner of Lincoln Street and Crow Point Lane.

In 1860, Peter was working as a shoemaker and his brother, Jacob, older by four years, as a cabinetmaker. The seven siblings, the youngest of whom, John, had been born four days before his father’s death in 1856, were living with their widowed mother, Agnes, and their maternal grandmother, Catherine.

On 22 May 1861, twenty year-old Jacob volunteered for service with Hingham’s Lincoln Light Infantry (a company of the Fourth Massachusetts Volunteer Militia) and was sent to Fortress Monroe in Virginia, a key staging area for northern campaigns. Later serving with the 30th Regiment, he survived the war – though he was wounded at Cedar Creek in October 1864 – and was mustered out in July 1866. He returned to Massachusetts where he married, raised a family, and operated a grocery store in Boston.

During that spring of 1861, Peter watched as his brother, along with other older boys of Hingham, had said their goodbyes and marched off together to fight for the Union cause. On 2 December 1861, the then-sixteen-and-a-half year-old Peter lied about his age (the minimum age for Union recruits was eighteen) and enlisted with the 32nd Regiment Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, Company E. He served as a private until October 1862 when he was promoted to full corporal, then reenlisted for a three-year term and was promoted to sergeant in January 1864.[1]

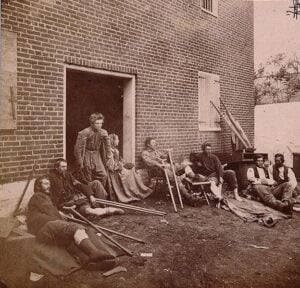

Wounded soldiers from the Battle of the Wilderness (5-7 May). Image created 20 May 1864. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Wounded soldiers from the Battle of the Wilderness (5-7 May). Image created 20 May 1864. Courtesy Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

On 9 June 1864, the Boston Evening Transcript, in its printed list of casualties,[2] included the name of Peter Ourish of the 32nd Regiment. The list was transmitted on 30 May, the day Peter had been wounded at Totopotomoy Creek, but by the time it was published, Peter had died Stanton Hospital in Washington, D.C., on 8 June. The field hospital, a group of one-story wooden hospital wards, had opened in 1862 to receive wounded Union troops and was named for Secretary of War Edwin Stanton.

One document registering the deaths of volunteers indicates Peter’s cause of death as VS Arm, the term VS (Vulnus sclopetarium), an esoteric and now virtually obsolete term for gunshot wound.[3] A second document, listing burials on military posts and in national cemeteries, offers additional details, citing Peter’s cause of death as exhaustion following amputation. He was initially buried in the Soldiers’ Home Cemetery (United States Soldiers’ and Airmans’ Home National Cemetery) in Washington, but was exhumed on 13 June 1864 and returned to Hingham. On 19 June, the Rev. Joshua Young delivered the eulogy at the New North Church (Third Parish) after which family, friends, and townsfolk accompanied Peter to his final resting place in the Ourish family plot.

One hopes that his mother was able to visit with [Jacob] before her death that December, two days after Christmas, at the age of fifty.

One can’t help but think about Peter’s widowed mother Agnes enduring that sorrowful day, and that as she buried Peter her first-born, Jacob, was still at war. On 19 September 1864, only weeks after his brother’s funeral, Jacob was engaged in heavy fighting at Opequan in Virginia where Union casualties numbered 5,000 and Confederate casualties 3,600. A month later, he was wounded at Cedar Creek (8,800 total casualties) but was able to take his convalescence at the newly opened facility in Readville, Massachusetts (now Hyde Park). One hopes that his mother was able to visit with him before her death that December, two days after Christmas, at the age of fifty. Her will, written on 16 December 1864, includes a poignant instruction that her three youngest children receive “all the money, bounties, arrears of pay etc. due and coming to me from the State of Massachusetts, and from the United States, by reason of the death of my son, Peter Ourish, late Sergeant in Company ‘E’ in the 32nd Regt. Massachusetts Volunteers.”

The grave of Peter Ourish is steps away from the Civil War monument, an obelisk made of Quincy granite that was dedicated by the town in 1870. It bears the names of more than seventy honored dead, including Peter, who gave “the last full measure of devotion.” Each of those soldiers has a story as harrowing as Peter’s. How much more engaging the cemetery would be if, somehow, those stories could be told.

Notes

[1] The staggering total casualties during the Civil War battles in which Peter Ourish participated included 51,000 at Gettysburg, 29,800 at The Wilderness, 24,000 at Chancellorsville, and 22,717 at Antietam. The loss of 620,000 lives in the Civil War nearly matches the death toll from all other American wars combined.

[2] Not to be used interchangeably with fatality (death), a casualty of war was the inability to perform basic duties due to death, wounds, injury, sickness, internment, capture, and [being] missing in action.

[3] For an interesting discussion of the etymology of the term, see the Baylor University Medical Center article, Vulnus sclopetarium at National Center for Biotechnology Information, www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov.

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →