Christmastime in Germany is magical. Winter is generally a cold, dark season, but for most of November, and all of December, it seems like every open square in large towns and cities all over the country is taken over by holiday spirits as the Weihnachtsmärkte and Christkindlmärkte (Christmas markets) are built. Wooden stalls go up, and decorations adorn the streets. At night, twinkle lights go on, braziers are lit, and the Glühwein starts flowing. In the absence of a national holiday in November, Germany and neighboring countries like the Netherlands and Austria devote the late fall and early winter exclusively to Christmas, building up to Santa’s visit on Christmas Eve.

Christmastime in Germany is magical. Winter is generally a cold, dark season, but for most of November, and all of December, it seems like every open square in large towns and cities all over the country is taken over by holiday spirits as the Weihnachtsmärkte and Christkindlmärkte (Christmas markets) are built. Wooden stalls go up, and decorations adorn the streets. At night, twinkle lights go on, braziers are lit, and the Glühwein starts flowing. In the absence of a national holiday in November, Germany and neighboring countries like the Netherlands and Austria devote the late fall and early winter exclusively to Christmas, building up to Santa’s visit on Christmas Eve.

While in the U.S., Santa and St. Nick are interchangeable, in parts of Central Europe St. Nicholas still has his own day—December 6. On the night of the fifth, children leave their shoes out, along with snacks for St. Nicholas’s horse. In return, St. Nick fills the children’s shoes with candy and fruit.

While in the U.S., Santa and St. Nick are interchangeable, in parts of Central Europe St. Nicholas still has his own day—December 6. On the night of the fifth, children leave their shoes out, along with snacks for St. Nicholas’s horse. In return, St. Nick fills the children’s shoes with candy and fruit.

The German language is one of many dialects and regional traditions, and the holiday gift-bringer had a wide variety of names across the country. The name “Santa Claus” itself is said to be a variant of the Dutch “Sint Nikolaas.”

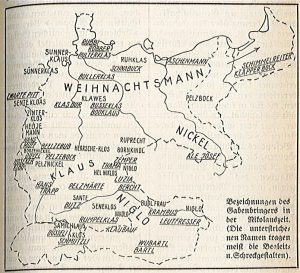

In 1936, Oswald A. Erich and Richard Beitl published the Wörterbuch der deutschen Volkskunde (Dictionary of German Folklore). They wanted to create a comprehensive collection of common folk stories and traditions. Among their interests: who delivered gifts on Christmas? Along with a description of beliefs about St. Nicholas, they created a map of “Names of Gift-Bringers in the Season of St. Nicholas.”

The map shows four overarching names, roughly one each for the northern, southern, eastern, and western parts of the country. These are Weihnachtsmann, Klaus, Nickel, and Niglo. Then there are more specific regional names, typically derived from local slang or dialects, such as Helije Mann, Sunnerklaus, Nikolo, Klawes, and Sante.

Though many holiday customs brought over from Europe flourished in the U.S. (Christmas trees, advent calendars, ornaments, and Santa), one major tradition did not. St. Nicholas did not travel alone – while he distributed gifts to the “nice” children, his companion punished those who were “naughty.” Erich and Beitl show the names of these (underlined) on their map, too.

Though many holiday customs brought over from Europe flourished in the U.S. (Christmas trees, advent calendars, ornaments, and Santa), one major tradition did not. St. Nicholas did not travel alone – while he distributed gifts to the “nice” children, his companion punished those who were “naughty.” Erich and Beitl show the names of these (underlined) on their map, too.

The companion figures most well-known today are probably Zwarte Pitt, from western Germany on the border with the Netherlands, and Krampus, from the Alpine regions. But there are a number of other regional figures, like Rubbi-Robber, Busseklas, Schmützli, and Leutfresser (literally, people-eater!). The tradition of the Krampuslauf has become quite a spectacle, involving complex costumes and pyrotechnics display. The Lauf typically takes place on the night of December 5, the same night children prepare for St. Nicholas’s visit.

My sister and I, though several generations removed from our German immigrant ancestors, grew up setting out our shoes for St. Nick to fill with treats. Perhaps instead we should have spoken of Sunnerklaus!

Share this:

About Hallie Kirchner

Hallie Kirchner is a genealogist in the Research Services department. She is part of the team that performs research-for-hire for patrons. In addition to working with patrons to answer their family history questions, Hallie also helps with the Ask-A-Genealogist chat service and has worked on a variety of educational programs during her time at American Ancestors. Her areas of expertise include 19th-century America, Germany, and immigration. Prior to joining American Ancestors, she was part of the research team for the New York Family History Research Guide and Gazetteer. Hallie holds degrees in history and historic preservation. Areas of Expertise: 19th-century America, Germany, New York, New York City, Norway, Italy, westward migration, immigration history, and descendancy research.View all posts by Hallie Kirchner →