De Mortuis Nil Nisi Bonum. Since learning this saying in high school Latin class – “Of the dead, say nothing unless good” – I have heeded it as good advice for writing family history. If anything, many past genealogists exaggerate the virtues of forebears they never knew. With Edwin Herbert Morse of Wareham, Massachusetts (1849–1923), known as Herb, my great-great-grandfather, I had the opposite problem: no one among family or acquaintances had much good to say about him. And so, for more than three decades, I have struggled with whether I should pass on how Herb was remembered. Of course, had he been recalled with great fondness, I would have written his story long before now.

Herb Morse died when my grandfather Emory was 14. They lived in the same town, yet only met once. Why, I wondered? Emory responded, “Because he drank…,” as if I was expected to surmise the rest of the story. Another of Herb’s grandsons told me Herb’s second wife, Susie, “threw him out” near the end of his life. Most revealing were the reminiscences of Elizabeth LeBaron Meier, whose mother Lucinda Morse (1870–1973) was Herb’s cousin and neighbor: “Mother had no use for that man who brutalized his wife and children.” Not wanting to transmit snippets of hearsay alone, I hoped retrieving more facts about Herb Morse’s life might render him less of a one-dimensional villain.

Their appearance of genteel respectability belied a troubled house.

Herb’s father, Edwin Morse (1814–1892), a sawmill mechanic, endured the misfortune of two short marriages. His first wife, Thankful Ellis Gurney, died at 25, leaving him with three children. Edwin soon wed again to Rosilla Burgess, 20, of Sandwich, who bore two sons, Edwin Herbert and Millard Morse. Rosilla died at 26, leaving five-year-old Herb without a mother. Unusually for the time, Edwin Morse never remarried; his elder unmarried sister kept house for him. More sadness followed: Herb’s brother Millard succumbed to scarlet fever when he was 13, and his elder half-brother, Jennison Gurney Morse, a Civil War veteran, committed suicide.

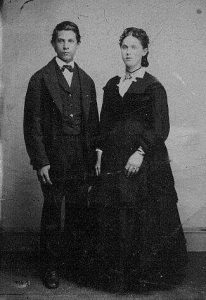

In 1875, Herb married the girl next-door, Emily Waters. Her father, Lewis Waters, and Edwin were lifelong friends.[1] A wedding tintype reveals that Herb looked boyish at 26 but had lost his right thumb, circumstances unknown.

The young couple prospered in a charming Victorian cottage on Papermill Road in Wareham. A badly faded photo captures the family with Emily standing in the yard, with daughter Edith and two sons, Millard (named after his uncle) and Burgess, faintly recognizable alongside the fence. Their appearance of genteel respectability belied a troubled house. Edith’s granddaughter told me her grandmother was not allowed to communicate with her maternal grandparents, the Waterses. They had to speak through a lilac hedge.

Edwin Morse bequeathed several parcels in Wareham and Rochester to his son Herb as the latter’s life began to unravel. Emily Morse never fully recovered from the birth of her last child, Edwin Lewis Morse, and died two years later from tuberculosis. After Herb married as his second wife 31-year-old Susie Morrill, a schoolteacher from Prince Edward Island, family divisions intensified when she named her son, Edwin Herbert Jr., even though Herb already had a son named Edwin. (The first Edwin went by Ned, and the second Edwin, like his father, went by Herb.) Herb eventually allowed his childless sister-in-law, Sadie (Waters) Loring, to adopt Ned, which added fuel to the resentment among siblings. Jealousy continued to fester when Susie’s sons, entirely on their own, eventually earned college degrees.

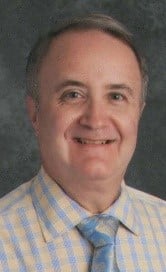

Herb Morse, granddaughter Emily, and daughter Edith Nickerson, in a photo taken shortly before his death in 1923.

Herb Morse, granddaughter Emily, and daughter Edith Nickerson, in a photo taken shortly before his death in 1923.

The lore that Herb lost most of his assets does indeed hold up to scrutiny in the steady sell-off of inherited property to settle debts. Once more, a photo does not convey the reality of a frayed family. While Herb lived with his son Burgess in Newton, Massachusetts, he sat for a three-generation family portrait with granddaughter Emily and daughter Edith. Note that Herb’s hand conceals the loss of his thumb.

Herb Morse left no estate to probate and, ironically, his widow Susie later bought the more modest house across the road that belonged to Herb’s first father-in-law, Lewis Waters. Susie’s son, Edwin H. Morse Jr., a lawyer and state legislator, later placed a marker on his father’s grave inscribed with Masonic insignia.

All the family members who kept afresh their scars from Herb Morse have long gone to their rest. What have I learned in the process of putting some flesh on this ancestral skeleton? While I cannot name all the demons that may have haunted my great-great-grandfather from childhood, addiction to alcohol, as well as some circumstances beyond his control, blighted his life.

Note

[1] For more on the Waters family, see “Inheriting Mayflower lines,” Vita Brevis, 24 April 2018.

Share this:

About Michael Dwyer

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →