The last of grandmother’s first cousins, Alma Rhodes of Westerly, Rhode Island, died on 4 August 2019 at the age of 96. She belonged to that increasingly rare group of individuals who lived in the house where she was born well into her nineties and worked for the same bank (albeit with multiple mergers) for 49 years.

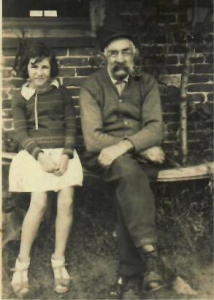

She was a portal to the early world of my grandmother, née Lois Rhodes, and passed along family letters and stories to me, thereby giving me a perspective that never could have come from public records alone. Alma visited her grandfather, William Henry Rhodes (1854–1941), almost every day and listened to his reminiscences, preserving them for another generation.

Alma was a portal to the early world

of my grandmother.

Alma’s father, Rodney C. Rhodes (1887–1960), a stone mason crippled by asthma attacks, had to abandon his trade by the early 1930s, and thereafter rely on the support of his older sons. On his doctor’s advice, Rodney kept a diary to relieve the tedium of a long day. Alma kept her father’s diaries in a wooden chest that he had carved. Rodney treasured family history and often used birthdays as way of reflecting on deceased relatives. Poring over his diaries with Alma became a staple of my annual visits.

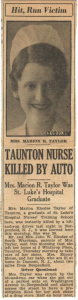

From adolescence I knew one family story by heart: the tragic death of my grandmother Lois’s only sister, Marion Rhodes Taylor, known as “Pinkie,” killed on 5 October 1934. Pinkie was a graduate nurse and recently married. She traveled by train from Taunton, Massachusetts, to Dumont, New Jersey, to care for Lois, who had spent eight weeks in the hospital following the premature birth of my mother (now age 85). Pinkie thoughtfully timed her arrival to coincide with Lois’s and baby’s first day home.

Pinkie had only a few hours to spend with her sister and new niece. That evening, in response to the baby’s cholic attack, Lois asked her husband (my grandfather) to pick up a prescription from a pharmacy in nearby Bergenfield. He complained that he was tired after a long day’s work, so Pinkie volunteered to go instead. She took my grandfather’s car and set out, thinking she would be back in less than half an hour. She never returned.

The police called my grandfather to come and identify the body. It turned out that, as Pinkie was crossing the street in front of the pharmacy, she was struck and killed by a hit-and-run driver. The crime was never solved. To the end of her life, my grandmother mourned Pinkie with the unanswerable question, “Why did God give me a child and then take my sister?”

Alma, then 11 years old, remembered the accident. Her father Rodney kept this newspaper clipping.

"All my life, I have often wondered,

what became of that baby?”

Front page news in the New Bedford Standard Times, 6 October 1934, with Pinkie’s age incorrectly listed as 26.

Front page news in the New Bedford Standard Times, 6 October 1934, with Pinkie’s age incorrectly listed as 26.

Pinkie was waked in her parents’ home in Wareham. Rodney’s subsequent diary entry, Monday, 8 October 1934, described how he, his wife Edith, and his sister Eva Clancy and her two children left Westerly at 9 p.m. to arrive in time for the funeral the next morning. It was the first time in 24 years of marriage that he and Edith had left their children alone.

In 1997, I met Alma’s sister, Helen Rhodes Werner, for the first time. After an absence of 52 years, widowed Helen had come home to Westerly to live with Alma. At first Helen had trouble understanding how I fit into the family. She eventually realized Lois was my grandmother.

What Helen next disclosed remains especially poignant. She and Pinkie had maintained their childhood friendship. Pinkie stopped in Westerly for an overnight stay on her way to New Jersey to see her sister. Helen said, “She slept upstairs with me in my bedroom. That was the last night of her life. The next day, she continued on to New Jersey to help Lois with her sick baby.” Helen’s eyes filled with tears, “The poor thing, mowed down by a big car. . . . All my life, I have often wondered, what became of that baby?”

“That baby is my mother,” I said. At that moment, I too experienced the deep sorrow of Pinkie’s death, piercing through the years. Thanks to Alma, I cherish this memory, along with many others.

Share this:

About Michael Dwyer

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →