Well, if there is one thing you should know about me, it’s that “I don’t do dishes.” Now don’t get me wrong, I always try to help set or clear the table come suppertime, and I’m never really opposed to that age-old argument of “who will wash and who will dry.” But past this, I’ve never had much, if any, interest in dishes themselves. And while I’ve always known that my adoptive great-grandmother’s Blue Willow[1] plates were to be treasured (and to be regarded as something more than just “plates”), as a kid I never figured them to be much good at all, since you couldn’t ever touch them or use them to serve up a big piece of birthday cake. I mean seriously, what good are dishes that just gaze out at you from a glass cabinet or scowl indifferently from the dining-room wall?

Yes, I’ve always felt this way—and well, in some ways, I admit, I (mostly) still do. This was especially true until one day several years back when a package arrived for me all the way from the wilds of Hollywood. It was a package that I had been eagerly anticipating, and it arrived swathed in an odd assortment of old postage stamps and a great deal of packaging tape. Its contents were likewise swaddled in, of all things, a couple of thick and well-worn beach towels. How very peculiar this package appeared to be, and in retrospect, how very Californian it all seems now.

My excitement in receiving this package was of course due to the nature of its contents. You see, under all the swaddling, the package contained what was the sole remaining possession of my biological great-grandmother Opal (Young) (Porter) Everett[2] who had passed away in North Hollywood in 1978. I had searched for Opal, a woman who had given up my biological grandmother for adoption in the spring of 1915, and a woman who, for lack of a better word, disappeared again about 1939. Through sheer serendipity and a lot of sleuthing, I had “found” Opal and her Last Will and Testament, and now I found this odd package which contained what was said to be her dearest possession arriving at my door.

In truth, Opal didn’t have much. Rumor had it that she’d worked as a humble manicurist at some of the Hollywood studios in the ‘30s, but I’ve never been able to substantiate any of that. Her second husband, Henry Lee Everett, doesn’t look to have had much either, and was possibly unable to provide all that well for a widow who would outlive him by nearly twenty years.[3] No, pretty much all Opal had in the way of worldly goods (so I’d been told) was a lot of old and yellowing “paperwork,” and, of all the strange things, an antique white ceramic soup tureen. Yes, a soup tureen—a dish so dear and precious to her that she even took steps to bequeath it “outside” of her own family—to the safe-keeping of her Executrix and best friend in the whole world.[4]

By the time I discovered Opal’s BFF, she had become quite elderly herself and seemed relieved that someone from Opal’s family—even a hitherto unbeknownst great-grandson—had come forward to claim all that yellow paper and the single soup tureen. Opal’s friend had asked me if I wanted the old pot, saying she thought that it need to be returned to the family. Needless to say, dish or not, I jumped at the chance. You see, for me to own a piece of my biological great-grandmother’s life—even an old dish—meant a kind of closure, a tangible representation of Opal’s life and her memory, for my family and the Young family for years to come.

Then, as I removed the lid, a yellowing letter fell out of the old pot, a letter that would give me some clues as to just what I was looking at—and just what it all might mean.”

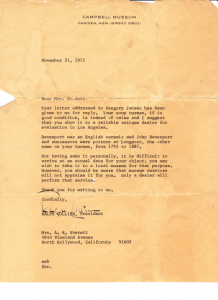

So, there it was on that sunshiny autumn day, an heirloom soup tureen unpacked in our kitchen. Good Lord, I had to wonder, what was I going to do with an old soup bucket like this? It wasn’t exactly a practical item or (for me) useful like a decent case of Sam’s Club Chinet.[5] Then, as I removed the lid, a yellowed paper fell out of the thing—a letter that would give me some clue as to just what I was looking at and just what it all might mean. It looks as if Opal had been somewhat of a ‘70s-style sleuth herself who had had questions about her own soup tureen. Seeming to sense that her soup tureen might not be just another run-of-the-mill porringer, she had written to (of all places) the folks at “M’m! M’m! Good! ®”[6] to find out more about just what she had. The Campbell Museum was opened in 1966 by executives of the soup company; their soup tureen collection now resides at Winterthur Museum in Delaware.[7]

Now, the origins of the actual soup tureen are straightforward. And, oddly enough, I have to wonder if dishes don’t have better luck in tracing their own ancestral origins than we do. The old pot’s ceramicists, Davenport Pottery of Longport, Staffordshire, look to have originated in England sometime between 1793 and 1887.[8] However, how Opal came to have this old vessel is a bit more obscure. It occurs to me that it most likely belonged to her mother, Mary (Neff) Young who might have received it as a wedding gift when she married Opal’s father George Alfred Young in 1884.[9] This is the most likely scenario. It is possible, too, that the tureen may have come down from Opal’s grandmother Elizabeth Freelove Sprague who married Opal’s grandfather Guilford Dudley Young in 1853, both of whom happen to be Mayflower descendants.[10] Both possibilities fit into the manufacturer’s time line. And yes, I guess it is also possible that it had been passed down from an even more distant point in time: from Opal’s great-grandparents, Alfred Young Jr. and Rebecca Johnson (Davis) Young, who both lived well into the 1870s.[11]

One thing is however certain: Opal took the reason why this old soup tureen was so precious to her to the grave. And in truth, the old pot’s value and its obscure journey from England to Connecticut to Kansas and on to Hollywood, in the end, don’t really matter. No, what truly matters here is that a tangible piece of the life of my great-grandmother, a woman I never would have known, exists. An item that will now stay (hopefully) safe, as it awaits the journey to its next destination, and the next of the Young family’s descendants.

Then, of course, there is the very evident genealogical conclusion to all this: that, yes, indeed, I do “do dishes.” (Wink!)

Notes

[1] “Blue Willow” is a crockery pattern; per Wikipedia, a style of dishware possibly originating in late 18th-century England.

[2] Opal (Young) (Porter) Everett (1895–1978).

[3] Henry Lee Everett (1892–1959).

[4] Emma Lou Peake (1919–2007).

[5] “Chinet®” is a registered trademark of Huhtamaki N.A.

[6] “M’m! M’m! Good! ®” is a registered trademark of the Campbell Soup Company; the slogan has been used in the company’s advertising campaigns since the 1930s.

[7] “Campbell Museum,” formerly at Camden, New Jersey; and as per Terry Pristin, The New York Times, 25 March 1996, “New Jersey Daily Briefing: Campbell Museum Closes,” 25 March 1996; it closed that same year (1996); http://www.winterthur.org/visit/museum/campbell-collection-of-soup-tureens/.

[8] From www.thepotteries.org: “John Davenport, born in 1765, is said to have begun potting in 1785, first as a workman, and later as a partner with Thomas Wolfe of Stoke. He acquired his own pottery at Longport for the manufacture of earthenware in 1794. In 1830 he retired, and his two sons Henry and William carried on the firm until 1835, when Henry died. This style of the firm then became William Davenport and Company. William died in 1869, and his two sons took over the direction of the business, which remained in the family until 1887.”

[9] Marriages of Butler County, Kansas, 1861–1885, FHL, states: “Young, George A., age 27, 27 March 1884 to Neff, Mary E. age 20.”

[10] Vital Records of Bolton., Conn., to 1854, states: “This certifies that Guilford D. Young of Tolland, Conn., and Elizabeth F. Sprague of Bolton, Conn. were by me joined marriage in the town of Bolton, on the 18th day of December 1853. . . .”

[11] Alfred Young Jr. (1800–1877) and Rebecca Johnson Davis (1804–1884) married at Chatham, Conn., 1 Jan. 1826.

Share this:

About Jeff Record

Jeff Record received a B.A. degree in Philosophy from Santa Clara University, and works as a teaching assistant with special needs children at a local school. He recently co-authored with Christopher C. Child, “William and Lydia (Swift) Young of Windham, Connecticut: A John Howland and Richard Warren Line,” for the Mayflower Descendant. Jeff enjoys helping his ancestors complete their unfinished business, and successfully petitioned the Secretary of the Army to overturn a 150 year old dishonorable Civil War discharge. A former Elder with the Mother Lode Colony of Mayflower Descendants in the State of California, Jeff and his wife currently live with their Golden Retriever near California’s Gold Country where he continues to explore, discover, and research family history.View all posts by Jeff Record →