My grandmother Anne (Cassidy) Dwyer never met her father, Patrick Cassidy, who was killed in a Fall River (Massachusetts) mill seven months before her birth, but from the Cassidy side of the family, she knew a dozen or more Irish-born first cousins. Six sisters from one family alone came to Fall River to escape the grinding poverty of rural Ireland. Agnes Horan, a favorite cousin, arrived at age 20 in 1908. Agnes’s elder sister, Annie Driscoll,[1] paid for her passage. Agnes, in turn, brought over the next sister. In 1919, after working ten years as a domestic servant, Agnes married Joseph Bento, son of Azorean immigrants. Agnes died in 1930, leaving her husband and four small children. For the rest of her life, Nana Dwyer nonetheless maintained contact with Agnes’s children. Long after my grandmother’s death, I renewed acquaintance with the Bento family, sharing genealogical information and photographs.

My research in County Mayo, Ireland, records placed Agnes as the eighth of twelve children born to John and Catherine (Cassidy) Horan. Several other facts about Agnes, however, had to be reconciled. First, Agnes was actually baptized as “Attie,” a diminutive of Attracta, an ancient Irish saint, and second, Agnes, in American records, sometimes deducted about dozen years from her true age to match her husband, a decade younger than she.

[Our] shared DNA relationships seemed to confirm these ties. A head-scratcher for sure!

With a bulging family file on the Cassidy and Horan families, collected over almost forty years, I was addled to see an online tree claiming “our” Agnes/Annie Horan married Charles W. Tyers in Manhattan on 20 April 1909. This could not be written off as a simple misattribution because Annie Tyers’s great-granddaughter, who posted the tree, shared 42 centiMorgans and two segments of DNA with me. Moreover, our shared DNA relationships seemed to confirm these ties. A head-scratcher for sure! Following a trail of both paper and DNA evidence solved the puzzle of Annie Horan Tyers’s correct parents yet exploded a bomb shell — of the kind I thought only happened in other people’s families.

The solution to the DNA mystery could be explained in the register of the parish church of Kilmovee, County Mayo: Two weeks before Catherine Cassidy wed John Horan, her sister Mary Cassidy married John’s brother, James Horan, on 25 January 1875. Children of the two couples, some bearing the same first and last names, were double first cousins.[2] James and Mary’s daughter, Hanoria, baptized in November 1882, is the one who as “Annie” married Charles Tyers, not Agnes. Annie also subtracted a few years crossing the Atlantic!

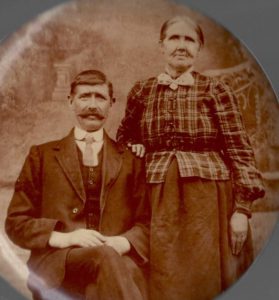

John Mary Horan and his mother, Mary (Cassidy) Horan, ca. 1910. (John’s middle name is a sign of his devotion to the Blessed Mother.)

John Mary Horan and his mother, Mary (Cassidy) Horan, ca. 1910. (John’s middle name is a sign of his devotion to the Blessed Mother.)

Until making this connection to Annie Tyers, I thought Mary (Cassidy) Horan’s family died out. Mary’s youngest daughter, Catherine (Horan) Holland, endured the tragedy of two sons killed during World War II. Another of James and Mary’s daughters, Bridget Horan, also emigrated to Fall River. Like her cousin Agnes Bento, Bridget adopted a new name, “Beatrice,” and a new birth date, minus four the original, to marry a younger man who abandoned her early in the marriage. Beatrice raised three sons; two never married and the third son, Tom, never had children. Tom, the last survivor, and “the end of the line,” entrusted me with family memorabilia, including this cherished photo of Mary Cassidy Horan and her son John Mary. Once she left Ireland, Beatrice never saw her mother again. The original image, a sepia celluloid disk, ca. 1910, will eventually find a home with one of Mary’s newly discovered descendants.

Now the bombshell, brought to light through another online tree, verified through DNA and personal contact: Bridget/Beatrice Horan has a living grandson! Those details I withhold for privacy’s sake. Suffice it to say, the story continues. I can empathize with all the conflicting emotions and questions that a late-in-life NPE revelation carries with it. In addition to the sensitivity we must practice when DNA evidence takes us to new genealogical thresholds, we also need to be careful that among families with endogamous marriages, shared DNA does not lead us to the wrong set of parents.

Notes

[1] Baptized as Hanoria.

[2] For more on the Cassidy family, see Michael F. Dwyer, “Hart-Cassidy Migration from the Parish of Kilmovee, County Mayo, to Fall River, Massachusetts,” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register 166 [2012]: 100–14.

Share this:

About Michael Dwyer

Michael F. Dwyer first joined NEHGS on a student membership. A Fellow of the American Society of Genealogists, he writes a bimonthly column on Lost Names in Vermont—French Canadian names that have been changed. His articles have been published in the Register, American Ancestors, The American Genealogist, The Maine Genealogist, and Rhode Island Roots, among others. The Vermont Department of Education's 2004 Teacher of the Year, Michael retired in June 2018 after 35 years of teaching subjects he loves—English and history.View all posts by Michael Dwyer →