“You know, there is a shortage of beautiful, old theaters left in this country and this is one of them…” – Daryl Hall

“You know, there is a shortage of beautiful, old theaters left in this country and this is one of them…” – Daryl Hall

At some point during the first decade of 2000s, I went to see Hall and Oates at the Orpheum Theater in Boston. They were on a tour to promote a Christmas music album they released earlier that year, but I don’t think I knew that and I don’t know that many people in the audience did either. I went there to see Sarah Smile performed live, just like everyone else. When they were about to start their fifth consecutive Christmas folk song of the night, the entire theater whined in unison, and Daryl Hall was not amused. A known curmudgeon, he motioned for the band to stop playing before he disembarked the clown car of complaints about the esthetic and operational state of the theater. He said that he had seen quite a few such old auditoriums, that the one we were all together in at that moment was one of the most beautiful, and what a shame for the current owners not to value its charm and elegance.

It got me thinking that I really knew nothing about the building, one where I had seen so many concerts in my lifetime and a place that is, without a doubt, my favorite place to see a show. To be honest, that statement is the most memorable moment of that evening. I couldn’t tell you their set. The reason for this could be that perhaps I was too wrapped up in the other memory created that night, as it was the second time in my life where I had been in within arm’s length of Boston College (and Heisman Trophy-winning) quarterback Doug Flutie at a concert. (The other time was Aerosmith at the Garden on New Year’s Eve 1996. You couldn’t get more Boston in your Boston if you tried.)

I’ve never forgotten Daryl Hall’s diatribe, nor has my curiosity waned about his comments.

Coincidentally, of late I have been revisiting Ken Burns’ Civil War documentary series. The third episode outlines the process and execution of the Emancipation Proclamation, the executive order meant to free slaves in the rebellious states, effective 1 January 1863.[1] The end of the episode highlighted the eve of the order and a celebratory and emotional gathering of abolitionists including Harriet Tubman, William Lloyd Garrison, and Frederick Douglass: “The cheering crowd called for Harriet Beecher Stowe, [and] she stood in the balcony, tears in her eyes.”[2] This event, on the eve of one of the most important Presidential directives in our history, was held in Boston at the Music Hall.[3] I knew nothing about the Music Hall other than no longer exists. Since I want to know about everything, I had to dig into the details of the Music Hall and why I hadn’t known the details about this profound and important moment before. I wanted to know where the Music Hall stood.

This event, on the eve of one of the most important Presidential directives in our history, was held in Boston at the Music Hall.

Using funds raised by Harvard’s Music Society,[4] Boston’s Music Hall was constructed in 1852 from designs by Back Bay architect George Snell.[5] The 2000-seat theater held its grand opening on 20 November of that year. The print publication The New England Farmer reported that the hall was “completely hemmed in by brick walls on every side” and “perfectly harmonious in it’s proportions” at 65 feet high (thirteen feet taller than New York’s Metropolitan), 78 feet wide, and 130 feet long. For the first five years of its life, the Music Hall leased a Sunday evening residency to the Handel and Hayden Society.[6] It was also the first home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra when it was founded in 1881.[7]

All sorts of events were held at the Music Hall. Political debates, plays, and sermons were among the well-attended occasions there. Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803–1882) delivered a lecture on his essay “Immortality,”[8] and Louisa May Alcott performed a stage adaptation of Dickens’ Mrs. Jarley’s Waxworks there.[9] In 1882, Oscar Wilde addressed a standing-room-only crowd where several Harvard undergraduates dressed as Wilde “lookalikes.”[10] A great number of anti-slavery orations were given by notable reformers and abolitionists at the Music Hall. Theodore Parker (1810–1860) delivered weekly sermons denouncing the Fugitive Slave Act[11] and Fredrick Douglass presented a “thrilling story of the John Brown raid.”[12]

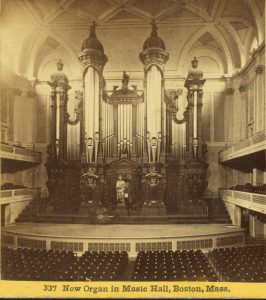

During the summer of 1863, the Music Hall was closed to the public so that the famous pipe organ, often referred to as The Great Organ, could be installed. From the opening eleven years earlier, it was the dream of the Hall’s director to have “an organ of the first class,” so he organized the Organ Committee of the Directors of the Music Hall Association to raise the funds and procure “an organ … that shall rival in power, in magnitude, and in excellence, the famous instruments of the old world.”[13] The instrument was designed overseas by E. F. Walcker of Ludwigsburg, Germany,[14] with reported costs fluctuating between $60,000[15] and $88,000.[16] The 2nd of November 1863 saw the well-prepared (and sold out) grand introduction of the new instrument at the Music Hall. The program consisted of Bach’s Trio Sonata in E flat performed by John K. Paine, organist at the West Church, Boston, and Musical Instructor at Harvard University; Mendelssohn’s Grand Sonata in A, No. 3 performed by B.J. Lang, organist of the Old South Church and of the Handel and Haydn Society, and others.[17] The Boston Daily Journal reported: “Seldom has there been a more brilliant gathering of men and women, renowned in intellectual, scientific and artistic attainments. The occasion was worthy of their presence, for it was a successful consummation of long-continued, patient, preserving effort to give an Imperial instrument to Republican America!”[18]

During the summer of 1863, the Music Hall was closed to the public so that the famous pipe organ, often referred to as The Great Organ, could be installed. From the opening eleven years earlier, it was the dream of the Hall’s director to have “an organ of the first class,” so he organized the Organ Committee of the Directors of the Music Hall Association to raise the funds and procure “an organ … that shall rival in power, in magnitude, and in excellence, the famous instruments of the old world.”[13] The instrument was designed overseas by E. F. Walcker of Ludwigsburg, Germany,[14] with reported costs fluctuating between $60,000[15] and $88,000.[16] The 2nd of November 1863 saw the well-prepared (and sold out) grand introduction of the new instrument at the Music Hall. The program consisted of Bach’s Trio Sonata in E flat performed by John K. Paine, organist at the West Church, Boston, and Musical Instructor at Harvard University; Mendelssohn’s Grand Sonata in A, No. 3 performed by B.J. Lang, organist of the Old South Church and of the Handel and Haydn Society, and others.[17] The Boston Daily Journal reported: “Seldom has there been a more brilliant gathering of men and women, renowned in intellectual, scientific and artistic attainments. The occasion was worthy of their presence, for it was a successful consummation of long-continued, patient, preserving effort to give an Imperial instrument to Republican America!”[18]

The boastful excitement diminished when, in 1884, the Symphony Orchestra demanded stage space for instruments and musicians. The solution? Disassemble the 70 ton, 47 foot-wide, 18 foot-deep, and 70 foot-high $80,000 organ! At first, a new home at the New England Conservatory of Music seemed appropriate,[19] but the instrument lay in storage in an old barn behind the Conservatory until 1897,[20] perhaps too overwhelming in size and assemblage to contemplate refurbishing.

The solution? Disassemble the 70 ton, 47 foot-wide, 18 foot-deep, and 70 foot-high $80,000 organ!

In two ironic twists of happenstance, the organ met its fate outside our fair city.

The first: she sold at auction for $1500.00 to E.F. Searles,[21] an interior and architectural designer who married into wealth and built the Serlo Music Hall in Methuen, now named Methuen Memorial Music Hall, specifically to fit the rebuilt organ. Searles is also the builder and former inhabitant of the Searles Castle in Great Barrington, Massachusetts.

The second? In 1900, the BSO removed to the newly-built Symphony Hall on Huntington Avenue and the Music Hall closed.

Six years later, the Hall reopened. In 1916, her interior was refitted by Thomas W. Lamb, who outfitted the Palace Theater in Waterbury, Connecticut; the Ziegfeld Theater in New York; and the Fenway Theatre, which today we know as the Berklee Performance Center.[22] Her main entrance changed from Winter Street to a dead-end alley off Tremont Street. The new theater operated through a few incarnations in its reintroduction as both a vaudeville theater and a movie house operated by Loews. [23]

And the Music Hall was renamed the Orpheum.

In 1970s, the theater began showcasing musical acts under ownership of African American entrepreneur-activist Arthur Scott. Its first featured performer, on 28 October 1972, was James Brown.[24]

I had so many thoughts about subjects to write about for in February to remember and revere the African descendants of American History. I’m grateful to have the information to connect all these symbolic dots. To think that within the walls of the rundown Orpheum Theater are the echoes of progressive thought from Transcendentalist authors and reformers; that a place survives where Frederick Douglass stood and wept on the eve of the Emancipation Proclamation; where a peak experience of my life was singing “Let Love Rule” in unison with the entire theater; where Lenny Kravitz finished his show and left the stage only to come back to tell us all how beautiful we sounded; where James Brown was the first musical act, the man who, only four years earlier at the Boston Garden (on 5 April 1968), calmed down an angry and emotionally reactive crowd, thwarting violent aggression the night following the assassination of Martin Luther King, Jr.

Daryl Hall was right. There is a shortage of beautiful theaters left in this country and the Orpheum is one of them, if only in spirit.

Notes

[1] “Transcript of the Proclamation,” National Archives; https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/featured-documents/emancipation-proclamation/transcript.html (accessed 1 February 2019).

[2] The Civil War, Ken Burns, Public Broadcasting Service, 1990 (accessed 1 February 2019).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Paul E. Teed, A Revolutionary Conscience: Theodore Parker and Antebellum America (Lanham, Md.: University Press of America, 2012), 147, at Google Books (accessed 31 January 2019).

[5] Anthony Mitchell Sammarco, Downtown Boston (Mt. Pleasant, S.C.: Arcadia Publishing, 2002), no page number, at Google Books (accessed 31 January 2019).

[6] The New England Farmer, 9 October 1852; https://www.newspapers.com/image/404591177/?terms=boston%2Bmusic-hall (accessed 31 January 2019).

[7] The History of Symphony Hall, Symphony Hall; https://www.bso.org/brands/symphony-hall/about-us/historyarchives/the-history-of-symphony-hall.aspx (accessed 31 January 2019).

[8] Mary Melvin Petronella, Victorian Boston Today: Twelve Walking Tours (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2004), 87, at Google Books (accessed 31 January 2019).

[9] Petronella, Victorian Boston Today: Twelve Walking Tours, 87.

[10] Ibid., 88.

[11] “Theodore Parker,” The Dictionary of Unitarian and Universalist Biography; http://uudb.org/articles/theodoreparker.html (accessed 1 February 2019).

[12] “Fred Douglass Lecture,” The Boston Globe, 21 May 1886, at Newspapers.com; https://www.newspapers.com/clip/27502030/boston_globe21may1886p3fred_douglass/ (accessed 31 January 2019).

[13] The Great Organ in the Boston Music Hall (Boston: Ticknor and Fields, 1865), 13, at Google Books (accessed 31 January 2019).

[14] Methuen Music Hall, Boston Organ Studio; http://www.bostonorganstudio.com/methuen-memorial-music-hall/ (accessed 1 February 2019).

[15] “Famous Organ Sold for Song” The Boston Globe, 13 May 1897, at Newspapers.com; https://www.newspapers.com/image/430761997/?terms=music%2Bhall%2Borgan (accessed 31 January 2019).

[16] “Must the Great Organ Go?,” The Boston Globe, 7 September 1882, https://www.newspapers.com/image/428924366/?terms=music%2Bhall%2Borgan (accessed 31 January 2019).

[17] The Great Organ in the Boston Music Hall, 74.

[18] The Great Organ in the Boston Music Hall, 77.

[19] “Famous Organ Sold for Song,” The Boston Globe, 13 May 1897 [see Note 15].

[20] “Once Musician’s Pride: Old Music Hall Organ to be Sold at Auction May 12,” The Boston Globe, 30 March 1897, at Newspapers.com; https://www.newspapers.com/image/430863379/?terms=music-hall%2Borgan (accessed 31 January 2019).

[21] “Famous Organ Sold for Song” The Boston Globe, 13 May 1897 [see Note 15].

[22] Ibid.

[23] Wikipedia contributors, wikipedia.org, “The Orpheum Theater (Boston),” 22 January 2019, Wikipedia.org, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Orpheum_Theatre_(Boston) (accessed 1 February 2019).

[24] Ibid.

Share this:

About Susan Donnelly

Susan is a native New Englander and second generation American from a large extended family of artists. She spent two years with the Research Services team, working on several large projects, before joining Newbury Street Press. Prior to NEHGS, Susan was the director and auction coordinator with a premier antique gallery in Boston for two decades and an archival volunteer with the Hingham Historical Society. She received her B.A. in English Literature from Simmons College and holds a Professional Certificate in Genealogy from Boston University. Her research interests include Colonial America, royal ancestry, westward expansion, and U.S. migration trails. Susan is a photographer and potter and collects mid-century modern art.View all posts by Susan Donnelly →