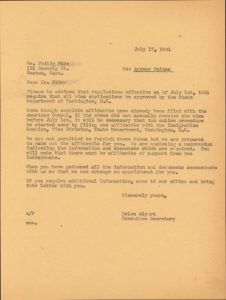

One example of the 1941 letter informing people that they would need to start their visa application process over again. Click on image to expand it.

One example of the 1941 letter informing people that they would need to start their visa application process over again. Click on image to expand it.

On the train from Washington D.C. to Boston this past summer, I sat next to an immigration lawyer by chance. Thanks to reading immigration case files all the time, I was proud that I could at least identify a few documents and steps in the immigration process he mentioned. I remember remarking how difficult it must be to understand the immigration process and navigate it successfully. Thinking about the encounter in hindsight, and after interning at the Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center for a year, I realized that the immigration process being difficult, tedious, and full of unexpected challenges isn’t exactly new.

During the Second World War, the U.S. State Department was notorious for its role in impeding the immigration of refugees, particularly Jews. Reflecting fears about German spies, the Department issued a so-called “relatives rule,” which instructed U.S. consuls abroad to deny visas to any applicant with close relatives in Nazi-occupied territory. Breckinridge Long, the State Department official who supervised the Visa Division, was notorious for his work to prevent emigration to the United States. Long even went so far as to write a memo in 1940, outlining how the State Department could block all immigration if necessary.

Few at the State Department did more than Long to prevent emigration of refugees. Long pressured Roosevelt to curtail the list of political refugees: that is, at-risk religious and intellectual figures who would have an easier time emigrating. Long also temporarily blocked news of Nazi mass murder from reaching the United States, for which the Treasury Department reported him to Roosevelt. When legislation appeared in Congress to urge creation of a separate commission for Europe’s Jews, Long gave false testimony and exaggerated the number of refugees admitted by the State Department.

Long pressured Roosevelt to curtail the list of political refugees: that is, at-risk religious and intellectual figures who would have an easier time emigrating.

One document I’ve seen multiple times in the Boston Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society case files, and a byproduct of the State Department, is a notice from July 1941. The notice advises the recipient that the State Department will now be handling visa applications. The letter spells out the consequences of this: “it will be necessary that the entire procedure be started anew by filing new affidavits.” Just like that, people were back to square one with their immigration cases. U.S. consulates were shut down in Nazi-occupied territory that same month, and the number of financial affidavits needed to emigrate was doubled. Visa applications now appeared before a government panel that included representatives from numerous military and security departments.

For those who filed new affidavits, the odds of approval were low. The State Department’s Interdepartmental Visa Review Committee was not required to provide reasons for denying visas, and agencies like HIAS Boston could often only speculate on why a visa had been denied. Consulates also had wide authority to deny visas. Secretary of State Cordell Hull advised consulates to take great caution in granting visas, and to err on the side of refusing them. In one case, a person with an affidavit from one of Boston’s wealthiest individuals was informed that their financial records were insufficient.

Some people were put on a waiting list before the war, endured and survived the war, and then discovered afterward that their number still hadn’t been called.

Many people didn’t get that far in the immigration process. In 1938, under the quota system, the waiting list for Germans emigrating to the United States was more than ten years long. One of the few things more disheartening than the 1941 visa notices are case files where people were put on waiting lists. Some people were put on a waiting list before the war, endured and survived the war, and then discovered afterward that their number still hadn’t been called. The German quota was filled in 1939 and almost filled in 1940, but increasingly strict immigration policies from the State Department led to a drop in visas issued, in spite of an enormous amount of applicants.

Working with the Boston HIAS case files over this past year has taught me a lot about the different obstacles and problems Jewish refugees faced, and the blatant government obstructions aiming at hindering their emigration. Simultaneously, I have also gotten to learn about the efforts of an organization and its partners to overcome those obstacles. Many cases don’t have a clear ending, but it’s heartening to know that for all the efforts to close the gate to Jewish refugees during World War II, there were groups that worked to hold it open.

Sources

Information from the Boston Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society case files, and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

The Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center’s Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society (HIAS), Boston Collection contains the case files and arrival cards of immigrants who received assistance from the HIAS Boston office between 1886 and 1977. Some records also include ship manifests, scrapbooks, passenger lists, photographs, and correspondence between immigrants, sponsors, officials, and HIAS Boston staff.

The case files are available to Special Researchers and NEHGS Research and Contributing Members. To learn more about the HIAS Boston collection, view the finding aid and the webinar, Using the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society Boston Collection. For more information or to request access to this collection, please email jhcreference@nehgs.org.

To learn more about the Wyner Family Jewish Heritage Center and its collections, visit the website.

Share this:

About Christopher Russell

Christopher Russell is a Digital Archives intern for the Jewish Heritage Center at NEHGS. He graduated from Oregon State University in 2015 with a B.A. in history and is pursuing his master’s degree in Library and Information Science at Simmons College in Boston, with a concentration in archive management. At the Oregon State Special Collections and Archives Research Center (SCARC), Christopher worked to scan and digitize portions of the Paul Emmett Collection, and contributed extensive research to the exhibit “Catching Stories: The Oral History Tradition at OSU.” Christopher also wrote for the SCARC blogs “Speaking of History” and “Oregon Multicultural Archives.” At NEHGS, Christopher helps to scan and digitize records from the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society.View all posts by Christopher Russell →