“As the flood itself has receded in Boston’s collective memory, so, too, have the players in this tragedy” - Stephen Puleo, Dark Tide

As genealogists, we build relationships with the dead. We see them in our minds as we peel back the layers of their lives. We absorb details about the environments where they lived and worked, and whether or not they had any time to play. Sometimes researching is like looking for a needle in a haystack; other times it’s like picking wildflowers in a field. When we have enough evidence, we write the stories of people we never knew.

I had intended to learn more about the Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 specifically to write about it for the centennial – but, like most projects, as my co-researchers will testify, our paths of discovery meander and often times produce an unexpected plot.

In my previous post, I referred to the online memorials of flood victims I read through. The most glaring detail in the chart of the deceased was the notation of a man who worked for the city in the North End paving yard, whose age at the time of death is reported as unknown. There is a footnote noting the lack of a death certificate for this victim, but that his wife provided testimony in the hearing to follow. This mention is consistent with Stephen Puleo’s Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 (2003), the most detailed published account of the flood. The victim’s name is recorded as James H. Kenneally.[1] He shared the same name as my paternal grandmother, Mary Ellen Kenneally (1904–1994), who, at the time of the flood, lived in Charlestown, just over the bridge that connects the North End to the rest of the world. I wondered if they were related somehow.

Before I read Puleo’s book, my knowledge of the Flood was superficial. I knew there was a spill in the North End and people died. My father told me that his mother, whom I called Nana, was walking home from school that day, and I gathered that stories of her experience had been passed on. It’s these details that allow me to better comprehend this distant situation. I could picture my grandmother there; a spectator in a white dress with holes in her shoes, carrying books held together with a strap, walking past a river of molasses to her home at 22 Albion Place. But I really don’t know that she did, and my father is gone now.

Before I read Puleo’s book, my knowledge of the Flood was superficial. I knew there was a spill in the North End and people died.

My great-grandparents, Catherine Kelly (1869–1951) and Daniel Kenneally (1867–1911), were Irish immigrants from County Cork, baptized in the same parish at Ballinhassig.[2] My great-grandfather died shortly after my grandmother turned seven. He worked for the Cunard Steamship Company, and fell from the deck of a White Star liner (think Titanic), fracturing numerous vertebrae. Though his certificate reads that he was 39 at the time of death, the number of years between my great-grandfather’s baptism and death is actually 44.[3] Such a discrepancy is a valuable reminder to consider when assembling the records of your ancestry. Who was the informant on the record? And how reliable was the informant? Errors on sources are not uncommon, and for this reason it’s important to support any evidence found. Checking facts with more than one source is crucial to weaving an accurate story.

Because of my experience in finding numerous errors in the reporting of vital records by non-researchers or genealogists, I felt the need to substantiate the claim that a death record for James Kenneally, Boston City worker and victim of the molasses flood, does not exist.[4]

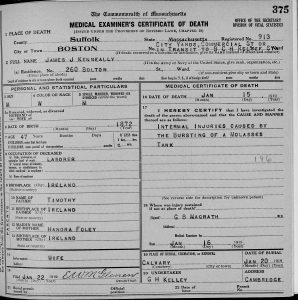

Through a quick vital records search online, I found it. The record reads James J. Kenneally, 260 Bolton St. in South Boston. His year of birth is 1872 and his parents were Timothy Kenneally and Honora Foley of Ireland. He is buried in Mt. Calvary in Roslindale. The cause of death on his certificate is “INTERNAL INJURIES CAUSED BY THE BURSTING OF A MOLASSES TANK.”[5]

Through a quick vital records search online, I found it. The record reads James J. Kenneally, 260 Bolton St. in South Boston. His year of birth is 1872 and his parents were Timothy Kenneally and Honora Foley of Ireland. He is buried in Mt. Calvary in Roslindale. The cause of death on his certificate is “INTERNAL INJURIES CAUSED BY THE BURSTING OF A MOLASSES TANK.”[5]

Taking his year of birth and the names of his parents, I went seeking a birth or baptismal certificate to find a connection between James Kenneally and my grandmother Mary Ellen.

And such a record exists: a baptismal certificate for a James born in August of 1870 to Timothy Kenneally and Honora Foley in Ballinhassig,[6] the same as my Kenneally great-grandparents. There is a discrepancy in the reporting of his age; the death certificate reads 1872, the baptismal record states 1870. I would value the baptismal record of his birth year, as it is closer to an original record of birth. His birth year on the death certificate is noted at the time of his death. As genealogists, we view records at the time of the event as original and others recorded later as derivative. In other words, the birth year on his death certificate is derivative.

While I have not yet completed my Kenneally family research, I have a strong belief that James Kenneally is the first cousin of my great-grandfather Daniel Kenneally. I believe their fathers, Timothy and Daniel, were brothers. I will continue to work on this question as I expand my knowledge of my ancestral origins.

As genealogists, we view records at the time of the event as original and others recorded later as derivative. In other words, the birth year on his death certificate is derivative.

So, here’s the thing: James Kenneally is often memorialized through accounts of the molasses disaster as James H. Kenneally, age unknown. As I mentioned before, this error is repeated in Dark Tide. The first report in the Boston Globe of the missing following the flood includes James Kenneally with middle initial H., yet each subsequent report which lists the names of victims reveals his correct middle initial J. When I am apprised of errors like this, I unpack the logic in my mind. Where did the H come from, and most importantly, how, after 100 years, has he been memorized incorrectly? A few reasons would be

- Amidst the chaos of the flood, a communicant mistakenly reported his name with the wrong initial.

- The impetus to the above error could be that someone with whom he worked looked at a record with his signature on it and the J looked like an H.

- It’s simply an error in reporting.

I don’t know how Puleo came to believe that there was no record for James Kenneally’s death. He so generously outlines his sources for organizing the story of the spill. But because of errors like this, Kenneally was not memorialized accurately. I do not blame Puleo, who is a brilliant writer and the very reason we have modern insight to the details of the molasses spill. Yet, I do encourage anyone doing family research to make sure you back up your evidence and treat discrepancies as errors both for and against your arguments.

James J. Kenneally was probably born in August 1870 in County Cork to Timothy Kenneally and Honora Foley. He married Mary O’Connell at Cambridge, Massachusetts on 26 May 1892. He worked for the City of Boston in the North End pavers’ yard and died tragically at Boston on 15 January 1919. He was 48.

Notes

[1] Stephen Puleo, Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919 (Boston: Beacon Press, 2003), 239.

[2] Ireland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1620–1911 [database on-line], ancestry.com, Ireland Births and Baptisms, 1620–1911. Index (accessed 4 January 2019).

[3] Ibid.

[4] Puleo, Dark Tide: The Great Boston Molasses Flood of 1919, 239.

[5] Massachusetts, State Vital Records, 1841-1920 [database on-line], familysearch.org, Death, Boston, Suffolk, Massachusetts, certificate number 913, page 375 (accessed 12 January 2019).

[6] Ireland, Select Births and Baptisms, 1620-1911 [database on-line], ancestry.com (accessed 4 January 2019) [see Note 2].

Share this:

About Susan Donnelly

Susan is a native New Englander and second generation American from a large extended family of artists. She spent two years with the Research Services team, working on several large projects, before joining Newbury Street Press. Prior to NEHGS, Susan was the director and auction coordinator with a premier antique gallery in Boston for two decades and an archival volunteer with the Hingham Historical Society. She received her B.A. in English Literature from Simmons College and holds a Professional Certificate in Genealogy from Boston University. Her research interests include Colonial America, royal ancestry, westward expansion, and U.S. migration trails. Susan is a photographer and potter and collects mid-century modern art.View all posts by Susan Donnelly →