One hundred years ago last week, my great-great-grandfather Hugh A. Crossen died on 9 December 1918. The Boston Globe noted that week that he was “one of the best-known old-time residents of the Parker Hill District” in the Mission Hill neighborhood of Boston. His funeral attracted “a large gathering of friends and relatives,” including “well-known” politicians: two state senators, two state representatives, and three former state representatives. The obituary even noted that the hymn “The Cross and Crown” was sung by a soloist during the funeral mass. Such high praise was not typical for an Irish immigrant who worked as a paper hanger. But Hugh Crossen had been an active Bostonian for more than seventy years, and his large family (nine children) made him a well-known neighborhood figure.[1]

Family stories suggested that Hugh died during the Great Influenza epidemic. He did not, however, die because of influenza. Rather, his death record notes that he had been afflicted by chronic myocarditis and chronic nephritis for six months prior to his death. He happened to die of those conditions during the epidemic in Boston, possibly leading his descendants to incorrectly remember or communicate the circumstances of his death.[2] His son, who had died seven weeks earlier at the age of thirty-nine, had been a victim of influenza and bronchopneumonia, so it seems that these two independent deaths might have been blended into a singular event in the oral tradition.[3]

Using the written record to interrogate family stories is an essential task for a genealogist.

Furthermore, Hugh had suffered from lung problems throughout his adult life, beginning during his service in the Union Navy during the Civil War, making it understandable that one might assume those health issues ultimately led to his death. Using the written record to interrogate family stories is an essential task for a genealogist. Finding documentation adds many layers to an ancestor’s life, and tracing Hugh’s experiences as a young adult has been a great interest of mine over the years. I am indebted to cousins and other relatives for their contributions to that research.

*

In October of 1859, Hugh’s father, who had worked for the Boston Water Department as a laborer, died and left his wife and three sons insolvent.[4] The fatherless Crossen boys found work on the docks of Boston Harbor as laborers and relied on their uncle, Manasseh, for additional financial support. Their mother, Nancy (Lynch) Crossen, remarried George McDermott on 1 June 1862; he was, by all accounts, a terribly unkind stepfather.[5]

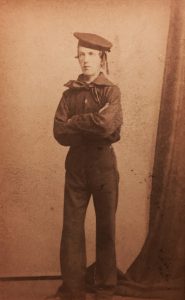

The eldest of the three children, Eugene, appears to have grown tired of McDermott quite early on. He enlisted in the Union Army just ten weeks after his mother’s second marriage, on 18 August 1862.[6] Hugh soon followed suit. On 14 October 1862, he joined a throng of other young men, claimed to be nineteen years old, and enlisted. Of course, he was only seventeen. The enlistment record reveals that he was 5’5½” tall and had blue eyes and brown hair.[7] One of my late grandmother’s cousins, a military historian, was able to help locate Hugh’s pension records from 1906. These papers reveal that Hugh bore two distinguishing marks – a scar on his nose, and a tattoo of his initials H.A.C and a shield.

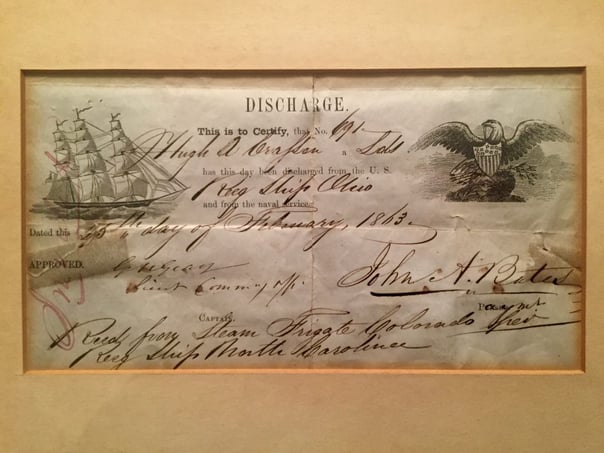

Military paperwork further reveals that Hugh served on the USS Ohio until 10 November 1862, when he was transferred to the USS Colorado, where he served until 22 January 1863. He was a landsman, a naval recruit with no experience.

While aboard the Colorado, Hugh was admitted for medical attention 18 January 1863. According to family stories, he had been stationed on the deck during a hurricane and developed what was first diagnosed as a severe cold. His pension relief application from 1906 revealed that his condition was indeed more severe. The attending physician noted in the ship’s medical journal that Hugh had developed phthisis pulmonalis, better known today as tuberculosis. The file detailed: “Has physical symptoms of deposit in apices of lungs with crepitus in both lungs posterior lower lobes, and sharp pain in right side. He is much debilitated and has considerable febrile disturbance.” He was soon transferred to the Chelsea Navy Hospital in Boston, where he received treatment until he was honorably discharged on 25 February 1863.

Despite the brevity of his service, Hugh was a proud veteran and a lifelong patriot. He never again saw his older brother, Eugene, who fought at Chancellorsville, Fredericksburg, and Gettysburg, only to die of tuberculosis as a captive at Andersonville Prison on 10 August 1864. Despite the loss of his brother and the enduring health issues from the war, Hugh encouraged his own sons to serve in the First World War – Joseph enlisted as a volunteer in the ambulance division, Henry served in the Army, and Robert served in the Navy. The last known photo of Hugh shows him standing before an American flag on Independence Day 1918, five months before he died.

*

I grew up visiting the graves of many of my ancestors, but I had never visited Hugh’s grave until a few years ago. He was not buried with his wife and children in Mt. Benedict Cemetery in West Roxbury, but rather in Cambridge, where his parents and infant sister had been buried. Because my late grandmother had mentioned that she remembered going to “Rindge Street” with her mother as a young girl, I was able to determine that Hugh was buried in North Cambridge Catholic Cemetery.

The signage in the cemetery is poor – some trees have faded letters on them, but no maps exist to guide visitors to a given grave. I had called the Archdiocese of Boston and learned the plot and grave where Hugh was interred; however, they were unable to provide any visual guide for finding the grave. I was undeterred, as it was a sunny fall afternoon, and so I meandered through the largely abandoned cemetery, strewn with fallen tree limbs and broken headstones, looking for clues.

After about an hour I came across a small military headstone. Occasional weed-whacking had disturbed the lowermost part of this stone enough that no moss grew across a band of a few inches, leaving the words “U.S. Navy” exposed. The rest of the stone was blanketed in a thick blanket of moss and indecipherable.

I crouched over, began scratching away the moss and lichen with a small branch. To my delight and amazement, the letters soon emerged in an arching, semicircular formation – HUGH A. CROSSEN. I felt like Indiana Jones. It was clear that I had been the first Crossen descendant in decades to visit Hugh’s grave. Since that initial visit, I have returned to North Cambridge Cemetery a few times.

Last weekend I visited Hugh’s grave on the 100th anniversary of his death to lay a wreath in his memory – a symbol that even though his natural life ended a century ago, he still lives on in the memory of his descendants. Although cemeteries are most obviously a reminder of death, they are also a testament to life lived, and I consider myself privileged to be able to research this one.

Notes

[1] The Boston Globe, Friday, 13 December 1918. Accessed via newspapers.com 7 December 2018.

[2] “Hugh A. Crossen,” Deaths Registered in the City of Boston, 1918, in Massachusetts State Vital Records 1841-1920. Family Search Film # 004966598. Page 345. Accessed via FamilySearch.org 7 December 2018.

[3] “Frank E. Crossen,” Deaths Registered in the City of Boston, 1918, in Massachusetts State Vital Records 1841-1920. Family Search Film # 004966598. Page 166. Accessed via FamilySearch.org 7 December 2018.

[4] “Hugh Crossan,” in Massachusetts Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988. Accessed via ancestry.com 7 December 2018.

[5] Boston Marriages 1862, in Massachusetts Town and Vital Records, 1620–1988. Accessed via ancestry.com 7 December 2018.

[6] "Eugene P. Crossen," in U.S., Civil War Soldier Records and Profiles, 1861–1865. Accessed via ancestry.com 7 December 2018.

[7] “Hugh A. Crossen,” in U.S., Naval Enlistment Rendezvous, 1855–1891. Accessed via ancestry.com 7 December 2018.

Share this:

About Alessandro Ferzoco

Alessandro graduated from Harvard University with an A.B. in History. While a student, he worked at Widener Library assisting patrons with research and training new employees. He is a lifelong resident of Boston, and enjoys local and social history. He is particularly interested in New England, Irish, and Italian ancestries. In 2017 he traveled to Italy to conduct research, and he has traced his patrilineal family to the early 1600s. He enjoys deciphering manuscripts and Latin parish records.View all posts by Alessandro Ferzoco →