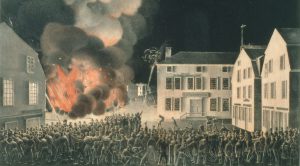

James Athearn's Washington House hotel on fire. Photo courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association, image 1896.0128.001.

James Athearn's Washington House hotel on fire. Photo courtesy of the Nantucket Historical Association, image 1896.0128.001.

In my last Vita Brevis post, I mentioned that an enormous wild fire had swept through the area where my maternal grandmother’s family has farmed for more than a century. A distant cousin told me, “The fire is total devastation for many: the total loss of this year’s crop, homes, combines, and equipment. For us it could have been much worse. We lost no equipment or buildings, only about 500 acres of wheat.” A tragic loss of the best crop folks could remember in many, many years.

While I’m terribly saddened by many farmers’ losses in my mother’s mother’s hometown, it is actually my father’s side of the family that has suffered a very long series of fires. The first instance I can document, thanks to the local paper’s short history of fires on Nantucket, occurred in 1836. On 2 January that year, a small fire broke out in the basement of James F. and Lydia (Starbuck) Athearn, my great-great-great-grandparents.[1]

The fire completely destroyed the inn and soon spread to other nearby buildings, creating the largest recorded fire on the island up to that time.

Four months later, on 10 May, a fire broke out in the chimney of the Washington House hotel on Main Street, owned by James F. Athearn’s father (also named James), where former President John Quincy Adams and his son had stayed the previous September. The fire completely destroyed the inn and soon spread to other nearby buildings, creating the largest recorded fire on the island up to that time.

Two years later, on 2 June 1838, the Athearn family suffered even greater losses when a fire broke out at a ropewalk[2] just a few blocks from the location of the now-defunct Washington House. As the fire began to spread, James Athearn, Sr. and his son and sons-in-law feverishly rolled barrels of whale oil out of their nearby warehouse and onto the surface of the nearby harbor, where everyone assumed they would be safe. Not so! A slick of oil allowed the fire to creep across the water, setting much of the harbor on fire. The 1876 article described it thus:

“Those who are now living, whose memory reaches back to that night, will never forget the sight of the blazing oil that covered the waters of the harbor south of Commercial wharf; nor the long tiers of iron hoops left standing in the place of the sheds stored with thousands of barrels of oil. So intense was the heat, that no charred remains of anything were left; but the whole district was burnt as bare as the shore beach. There were over one hundred sufferers by this fire, and the loss was estimated at from $150,000 to $300,000.” Contemporary accounts listed James Athearn as the biggest loser of the night.

So great was the devastation that the city of Nantucket took steps to prevent a cataclysm like this from ever happening again. Several cisterns were dug in the streets around town so that water would be readily available to fight any future fires. When the Liberty Street candle factory of James Athearn caught fire on 19 October 1840, it was only damaged slightly … and no one imagined that Nantucket’s “Great Fire” still lay in the future.[3]

"So intense was the heat, that no charred remains of anything were left..."

Around 11:00 PM on 13 July 1846, fire broke out in a Main Street hat shop located on almost the exact same spot where the Washington House hotel had burned a decade earlier! Two fire companies responded immediately but spent so much time arguing over who had earned the honor of putting out the fire that it got out of hand. “Between three and four hundred buildings were burned, and property to the amount of nearly $1,000,000 destroyed. Had the efforts to save the Methodist Church [on Centre Street] proved unavailing, the probability is that the whole of the northeast section of the town would have been burned.”[4]

Indeed, the entire business center had been wiped out, and many residences destroyed … including both the James Athearn and James F. Athearn houses, which had sat across Centre Street from one another. I can only imagine the terror my four-year-old great-great-grandfather must have felt awakening in the middle of the night, surrounded by fire, smoke, shouting, and panic. Or I could talk to my young niece and nephews about what happened to them last fall.

To be continued.

Notes

[1] Several details about Nantucket’s fires come from an 1876 article in the Inquirer and Mirror newspaper – no doubt compiled for the thirtieth anniversary of the Great Fire of 1846.

[2] A long, low building where navigational ropes were created.

[3] Boston radio host Doug “VB” Goudie self-published a book in 2016 about Nantucket’s Great Fire: ACK in Ashes. It’s a fascinating account of the 1846 Great Fire, as well as the two large fires preceding it. (The official call letters for Nantucket’s airport are ACK, and the letters have become a moniker for the island as a whole.)

[4] Inquirer and Mirror, Nantucket, 4 March 1876, 2.

Share this:

About Pamela Athearn Filbert

Pamela Athearn Filbert was born in Berkeley, California, but considers herself a “native Oregonian born in exile,” since her maternal great-great-grandparents arrived via the Oregon Trail, and she herself moved to Oregon well before her second birthday. She met her husband (an actual native Oregonian whose parents lived two blocks from hers in Berkeley) in London, England. She holds a B.A. from the University of Oregon, and has worked as a newsletter and book editor in New York City and Salem, Oregon; she was most recently the college and career program coordinator at her local high school.View all posts by Pamela Athearn Filbert →