I grew up with an understanding that I had German and Irish roots. My paternal grandfather would often pull out a few German phrases he learned from his grandparents. On my mother’s side my cousins and I all took great pride in being “Kiley girls.” While these identities were strong in my upbringing, it wasn’t until I was older that I realized my most recent immigrant ancestor was not German or Irish, but Czech – an identity that was not impressed upon me at all.

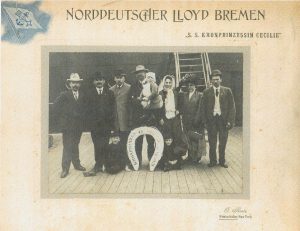

My father’s maternal grandfather, Joseph Kler, was born in Chicago in 1903 shortly after his family’s immigration. They returned to the old country for about three years while Joseph was a young child. A photograph of their return trip to the United States when Joseph was an adolescent hangs proudly in our living room.

Joseph had a passion for history – particularly American history.

Even though he had lived in what was at the time the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was old enough to remember his return voyage to settle permanently in the United States, Joseph was extremely proud of being American. He seemingly rejected any remnants of the old county. In a book of family papers compiled by my grandmother’s sister, Marjorie, she noted that her father anglicized the surname from Klir to Kler (as seen in official documents). She lamented the fact that she did not learn Czech as many of her cousins had. According to Marjorie, her father always said that they were Bohemian Czech, but the family story in the old country was not passed forward.

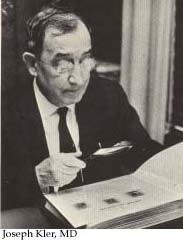

Once in the states permanently, Joseph was raised on a Wisconsin farm and then went to medical school. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical College in 1925 and served as a flight physician in the Navy. He was an ophthalmologist who practiced in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and was the chief of ophthalmology and otolaryngology at St. Peter's Medical Center for thirty years. But for all his medical training, he had a passion for history – particularly American history.

Once in the states permanently, Joseph was raised on a Wisconsin farm and then went to medical school. He graduated from the University of Pennsylvania Medical College in 1925 and served as a flight physician in the Navy. He was an ophthalmologist who practiced in New Brunswick, New Jersey, and was the chief of ophthalmology and otolaryngology at St. Peter's Medical Center for thirty years. But for all his medical training, he had a passion for history – particularly American history.

Joseph became a collector of pieces with historical significance. He also was a noted collector of historic pewter, Meissen china, and silver. His American pewter collection was so extensive that he donated the best pieces on permanent loan to the Smithsonian Institution. The remainder was sold by Christie’s Auction House. His Meissen china and silver appeared in the New Jersey State Museum in Trenton. He was also an avid collector of stamps with a medical theme, donating his rather large collection to the Cardinal Spellman Philatelic Museum at Regis College in Weston, Massachusetts – a museum of which he was a founder.

Joseph was also an architectural preservationist, organizing and leading the East Jersey Olde Towne project which saved historic structures from demolition and moved them to one site to recreate a colonial village. The entire project began with his effort to save the Indian Queen Tavern in New Brunswick, which quickly grew to a larger preservation effort. In an article on the creation of the village, Joseph noted, “We are interested in preserving a visual conception of our past so that young people can conjure up a picture of the way it was in Colonial times.”[1]

Joseph was also an architectural preservationist, organizing and leading the East Jersey Olde Towne project which saved historic structures from demolition and moved them to one site to recreate a colonial village. The entire project began with his effort to save the Indian Queen Tavern in New Brunswick, which quickly grew to a larger preservation effort. In an article on the creation of the village, Joseph noted, “We are interested in preserving a visual conception of our past so that young people can conjure up a picture of the way it was in Colonial times.”[1]

He also tried his own hand at writing history, composing a history of the Bound Brook Presbyterian Church.[2] Joseph’s family had been Catholic prior to their immigration, but his conversion to Presbyterianism and a marriage to a woman with deep colonial roots solidified his Americanism.

He spent his lifetime chasing the American dream and preserving a history which was not directly his own.

Joseph spent his lifetime chasing the American dream and preserving a history which was not directly his own, as none of his ancestors ever lived in colonial America. Evidence of the importance of American history in his life can be found in his obituary, which focuses more on his collections and preservation work than his career in medicine.[3]

From the perspective of his great-granddaughter, Joseph’s efforts were a part of his desire to truly be American and to pass on that pride of country to his children and their children. He saw himself as fully American. The sense of a Czech identity never reached me, though I know from learning more about Joseph Kler that his love of American history was passed to his daughter (my grandmother), to her son (my father), and then to me. I hope to carry forward Joseph’s sense of civic duty in the preservation of American history and by sharing his pride in being American.

Notes

[1] Muriel Freeman, “East Jersey Group Re-creating Village,” New York Times (November 4, 1973), 127.

[2] Joseph H. Kler, MD, God’s Happy Cluster: 1688-1973, History of the Bound Brook Presbyterian Church, (n.p., 1963).

[3] “Joseph H. Kler, 80, Physician and Preservationist in Jersey,” New York Times, (November 25, 1983), D00021.

Share this:

About Meaghan E.H. Siekman

Meaghan joined the American Ancestors staff in 2013 as a Researcher before moving to the Publications team in 2018 where she is currently a Senior Genealogist of the Newbury Street Press. As a part of the Publications team, Meaghan researches and writes family histories and other scholarly projects. She also regularly develops and presents lectures as well as other educational material on a variety of research topics. Additionally, Meaghan serves as the American Ancestor's representative to the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Meaghan holds a PhD in history from Arizona State University where her focus was public history and American Indigenous history. Prior to joining American Ancestors, she worked as Curator of the Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts and as an archivist at the Heard Museum Library in Phoenix. Meaghan also worked for the National Park Service and wrote several Cultural Landscape Inventories, most notably for Victoria Mine within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Her doctoral dissertation, Weaving a New Shared Authority: The Akwesasne Museum and Community Collaboration Preserving Cultural Heritage, 1970-2012, explored how tribal museum utilized shared authority with their communities. For American Ancestors, Meaghan authored Ancestry of Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch II in 2023, and Ancestry of Douglas Brinkley in 2019. She co-authored with Chistopher C. Child, Family Tales and Trials: Settling the American South in 2020. She also contributed to Ancestors of Cokie Boggs Roberts with Kyle Hurst in 2016. She has published portable genealogists on African American Genealogy (2015) and Native Nations in New England (2020). Meaghan has authored several articles in her tenure for American Ancestors magazine including most recently, “10 Myths about Slavery in the United States.” She has presented many lectures on African American genealogy, researching enslaved ancestors, researching the history of a house, using oral history in genealogical research, researching women, and other topics.View all posts by Meaghan E.H. Siekman →