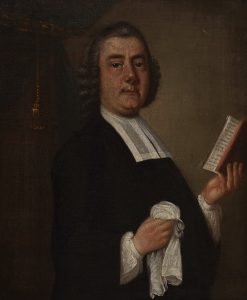

The Rev. Samuel Fayerweather (1725-1781), in the Society's Fine Art Collection. Gift of Miss Elizabeth Harris of Cambridge, Massachusetts, May 16, 1924.

The Rev. Samuel Fayerweather (1725-1781), in the Society's Fine Art Collection. Gift of Miss Elizabeth Harris of Cambridge, Massachusetts, May 16, 1924.

William Clark began keeping a journal in 1759 at the age of eighteen. He wrote an entry for almost every day until he died in 1815 at the age of seventy-five. The entire journal – fifty-six volumes and almost five thousand pages – is now held by the New England Historic Genealogical Society in Boston. Clark carefully recorded his neighbors’ births, marriages, and deaths, providing rich pickings for family history researchers, but the author of the journal is himself a fascinating character: a convert, a loyalist, and a refugee.

Clark was an Anglican clergyman by the time of the American Revolution, but – like many New England Anglicans – he had first joined the Church of England as a convert. His father, the Rev. Peter Clark, was a Congregationalist minister in Danvers, Massachusetts, and a leading “old light” defender of the colony’s Congregationalist establishment. William, too, was trained for the Congregationalist ministry, but he struggled to secure an appointment, perhaps because he was deaf. After a series of such frustrations, he conformed to the Church of England at the age of twenty-seven, sailed for England for episcopal ordination, and returned as an Anglican missionary to Dedham.

Understanding a convert's motives can be tricky. Clark's journal only provides clues: the disruption of his father's congregation by separatists, the political commotions occasioned by the Stamp Act, his search for permanent employment, and perhaps his frustration with the congregations that rejected a qualified minister with a physical disability. The only factor that he himself is clear about is the magnetic influence of another Anglican missionary, Rev. Samuel Fayerweather of Narragansett. In any case, Clark was not alone: there were ten Anglican missionaries in Massachusetts by the time of the Revolution, eight of whom were converts from Congregationalism. Clark's papers reveal how these converts brought something of New England's Puritan traditions with them into the Church of England.

When fighting first broke out, he kept his head down.

Clark’s uncompromising adherence to the principles of his new church encouraged him to view the American Revolution as nothing more than an unlawful rebellion. Nevertheless, he did little to actively resist it. When fighting first broke out, he kept his head down. He didn’t sign a loyalist address, publish a loyalist pamphlet, or join the King’s troops as a chaplain. Nor did he directly condemn the rebellion from the pulpit, as his surviving sermons (now at the Dedham Historical Society) make clear. After the British evacuated Boston in March 1776, Clark – like other Massachusetts loyalists – was left far from the protection of the royal army and part of a decidedly vulnerable minority. Remaining quiet was the safest bet. (At this point, Clark’s silence was still a matter of choice.)

Following the Declaration of Independence, however, Clark could no longer avoid confronting politics. The Anglican liturgy – which he read to his congregation every Sunday – contained prayers for the King. These prayers were quickly deemed treasonous to the newly independent American states: to read them would literally be to pray for the enemies of America. Some Anglican clergymen replaced the offending prayers with prayers for Congress. Others hedged their bets by omitting them altogether.

Clark decided to stop officiating publicly, rather than take it upon himself to modify the liturgy. Was this scrupulous orthodoxy, a sideways criticism of the rebellion, or both? Loyalism or neutrality? In either case, Clark’s refusal to support the Revolution was now a matter of public knowledge, and his days in Massachusetts were numbered.

Events overtook Clark the following year, when he wrote a letter of introduction for a loyalist member of his congregation. The next day a crowd gathered at his house, demanding he be arrested as an enemy to America. The revolutionary authorities complied, and Clark was sent to Boston, tried, and imprisoned on a boat in Boston harbor.

Clark’s refusal to support the Revolution was now a matter of public knowledge, and his days in Massachusetts were numbered.

During his ten weeks’ confinement, he was not treated badly – we shouldn’t imagine him languishing in chains in the hold – but his imprisonment seems to have exacerbated an existing illness, and his health deteriorated sharply. Already deaf, Clark now lost his speech as well. Given his poor health, he was transferred to house arrest, but was then faced with the hostility of his neighbors in a close-knit community. In the summer of 1778, after petitioning for permission to emigrate, Clark sailed for London for the second time in his life.

At this point his journal becomes rather depressing reading. Historians debate whether the American loyalists were really persecuted, or whether their alleged sufferings were mostly propaganda. Clark’s experience can be read both ways. In material terms, he had little to complain about. He was deprived of employment due to his ongoing ill health, and had lost the support of his social network, but he received a generous (if unreliable) loyalist pension.

More serious were the psychological hardships of exile. Clark’s journal records loneliness, isolation, low spirits, sleepless nights, anxiety about the future, and the pain of separation from his family, friends, and native country. Most distressingly, he received news of the death of his wife (who had remained in Massachusetts), but he was unable to find out how she died. He spent eight years in London.

Like many loyalists, Clark cared little about the abstract constitutional issues which aggravated the patriots. He wanted peace more than anything else. But when the eventual peace treaty recognized the independence of the American states, Clark’s identity was shattered. His loyalty was not to England – the distant and uncaring center of the Empire – but to a British Massachusetts which was now lost.

Like many loyalists, Clark cared little about the abstract constitutional issues which aggravated the patriots.

At a more practical level, American independence posed a dilemma: he could either continue to receive his loyalist pension, or return to his family and friends in Massachusetts, but not both. In 1786, he joined the flood of American loyalist refugees settling in Nova Scotia, where he remarried and remained for five years, but as soon as the British government gave him permission to emigrate, Clark gladly returned home, to the place he always referred to as his “native country.”

After everything he had been through, his reintegration into Massachusetts seems to have been remarkably painless. If he faced the hostility of his neighbors, he did not record it in his journal. As Rebecca Brannon’s recent book on the reintegration of the South Carolina loyalists suggests, the burden probably fell on Clark to seek the forgiveness in a series of face-to-face encounters: surely a painful process.

Clark’s reintegration was also presumably helped by the fact that he had become decidedly harmless. For the remaining twenty-five years of his life, he was essentially an invalid. Rarely able to go outside – let alone officiate – he was entirely dependent on his family and friends. His journal entries became longer as his days grew less eventful, providing ever-more detailed descriptions of his bodily infirmities. His last entry (almost illegible) is for 26 October 1815; he died nine days later.

How much does this journal tell us about its author? Often, frustratingly little. We are not talking about 5,000 pages of introspection, musings on public events, or self-narration. Instead, we read about the minutiae of every-day life. We learn which neighbors and friends Clark visited, and when, but not what passed between them. We learn an awful lot about the weather in Massachusetts. Clark sometimes seems to be deliberately oblique in his references to events which had a profound impact on his life.

A better question might be: why did Clark keep this journal? Undoubtedly, it was a spiritual exercise. He tallied up his blessings and, more often, his trials and hardships, while continually reminding himself of the irreversible passage of time, the inevitable approach of death, and the need to remain (as he put it) “indifferent to the world.” This world – the world of bodily infirmity, material suffering, psychological hardship, and separation from others – was transient, like water poured on the ground. Clark had more important things to worry about than the American Revolution.

Peter Walker wishes to thank the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium for supporting his research at the New England Historic Genealogical Society.

Update: In July 2020, Peter Walker gave a presentation on his work at a Zoom event via King's Chapel in Boston.

Share this:

About Peter Walker

Peter Walker received his Ph.D. from Columbia University in 2016. He is working on a book about the Church of England and the American Revolution. His article on “The Bishop Controversy, the Imperial Crisis, and Religious Radicalism in New England, 1764-74” won the 2016 Whitehill Prize from the Colonial Society of Massachusetts, and is published in The New England Quarterly for September 2017.View all posts by Peter Walker →