I have traced my husband’s paternal line back to Anthony Siekman, who was born in Germany about 1821. I knew from his petition for naturalization that he arrived in the United States in 1852, but I did not know much beyond that. As the progenitor of this line in America, I have Anthony to thank for the surname I carry after marriage and the name my children will carry into the world. Perhaps this is the reason why I first took an interest in piecing together the details of his life, but what I discovered was a tragic story that led to more questions.

I have traced my husband’s paternal line back to Anthony Siekman, who was born in Germany about 1821. I knew from his petition for naturalization that he arrived in the United States in 1852, but I did not know much beyond that. As the progenitor of this line in America, I have Anthony to thank for the surname I carry after marriage and the name my children will carry into the world. Perhaps this is the reason why I first took an interest in piecing together the details of his life, but what I discovered was a tragic story that led to more questions.

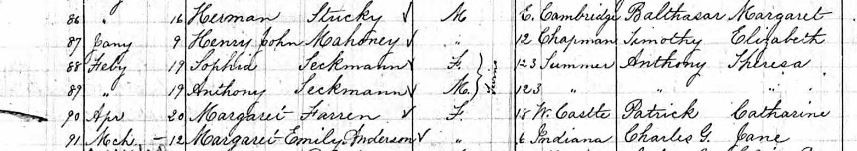

What first brought me to Anthony was the birth record of his twins, Anthony and Sophia, born on 19 February 1866 at 123 Summer Street in Boston to parents Anthony and Theresa Siekman.[1] However, I had difficulty locating the family in the 1870 United States Federal Census. Since the surname was spelled in a variety of ways across records, I tried every combination I could think of without any luck. I knew that the son Anthony grew to be an adult and have children in the Boston area, so I knew the family likely was still in Boston in 1870.

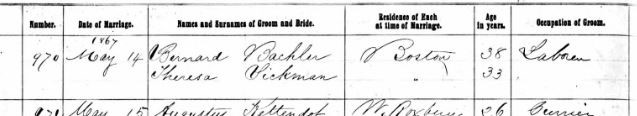

I discovered that the death of half the family was the reason I was not able to locate them. First, I found a marriage record for Theresa Sickman and Bernard Bachler at Boston on 14 May 1867.[2] This meant that Anthony’s wife, Theresa, had remarried before 1870 and would have been recorded in the census under her new married name. When I was able to locate the household, I learned that Anthony Jr. had been recorded that year under the surname of his stepfather, which is why I could not find them when searching for variations of the Siekman name. However, I also noted that the daughter Sophia was not in the household in 1870, signaling that both father and daughter had died before 1870.

I discovered that the death of half the family was the reason I was not able to locate them. First, I found a marriage record for Theresa Sickman and Bernard Bachler at Boston on 14 May 1867.[2] This meant that Anthony’s wife, Theresa, had remarried before 1870 and would have been recorded in the census under her new married name. When I was able to locate the household, I learned that Anthony Jr. had been recorded that year under the surname of his stepfather, which is why I could not find them when searching for variations of the Siekman name. However, I also noted that the daughter Sophia was not in the household in 1870, signaling that both father and daughter had died before 1870.

Sadly, Sophia’s death record indicated that she had died of scarlet fever at the tender age of three on 29 November 1869.[3] As a parent now myself, I always have a pause when finding the death record of a child, as I know that loss was sorely felt by the family. I also knew that poor Theresa lost her first husband before her second marriage. The loss of husband and child in such a short time must have been devastating.

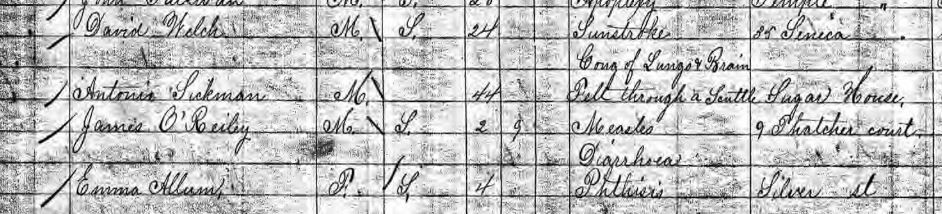

When I finally discovered Anthony’s death record, the story became even more heartbreaking. Anthony died on 17 July 1865 – seven months before his twins were born. His Boston death record states that the cause of death was a “fall through a scuttle” at “Sugar House.” A tragic accident that also contained a clue about where he was employed: it also explained why there were so few records for him in Boston.

When I finally discovered Anthony’s death record, the story became even more heartbreaking. Anthony died on 17 July 1865 – seven months before his twins were born. His Boston death record states that the cause of death was a “fall through a scuttle” at “Sugar House.” A tragic accident that also contained a clue about where he was employed: it also explained why there were so few records for him in Boston.

The twins, Anthony and Sophia, were the only children born to Anthony and Theresa, and all the Siekmans in the Boston area I have located descend from the one child of theirs who survived. Theresa remained close to her son, often appearing in his household when he was an adult. How challenging her young adulthood must have been, arriving in Boston from Germany as servant in 1860 and suffering successive losses during her first decade in the United States.

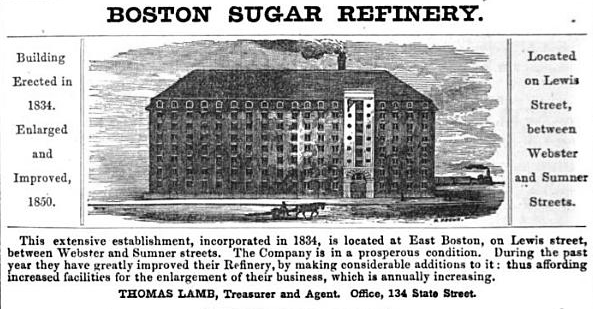

My new project is to see if I can determine which “Sugar House” may have employed Anthony Siekman. There were a few sugar refineries in Boston at the time of his death, including the Boston Sugar Refinery and the Union Sugar Refinery. An address was not included in the death record, though the birth record of the twins seven months later states their address as 123 Summer Street in Boston. I am in the works of triangulating which refinery may have been closest to their address; I can then determine what records may still exist to lead me to more information about Anthony. As with every genealogical venture, answers always seem to lead to more questions.

My new project is to see if I can determine which “Sugar House” may have employed Anthony Siekman. There were a few sugar refineries in Boston at the time of his death, including the Boston Sugar Refinery and the Union Sugar Refinery. An address was not included in the death record, though the birth record of the twins seven months later states their address as 123 Summer Street in Boston. I am in the works of triangulating which refinery may have been closest to their address; I can then determine what records may still exist to lead me to more information about Anthony. As with every genealogical venture, answers always seem to lead to more questions.

Notes

[1] Massachusetts Vital Records, 1866, Boston, 188: 32.

[2] Massachusetts Vital Records, 1866, Boston, 201: 54.

[3] Massachusetts Vital Records, 1866, Boston, 222: 193.

Share this:

About Meaghan E.H. Siekman

Meaghan joined the American Ancestors staff in 2013 as a Researcher before moving to the Publications team in 2018 where she is currently a Senior Genealogist of the Newbury Street Press. As a part of the Publications team, Meaghan researches and writes family histories and other scholarly projects. She also regularly develops and presents lectures as well as other educational material on a variety of research topics. Additionally, Meaghan serves as the American Ancestor's representative to the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Meaghan holds a PhD in history from Arizona State University where her focus was public history and American Indigenous history. Prior to joining American Ancestors, she worked as Curator of the Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts and as an archivist at the Heard Museum Library in Phoenix. Meaghan also worked for the National Park Service and wrote several Cultural Landscape Inventories, most notably for Victoria Mine within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Her doctoral dissertation, Weaving a New Shared Authority: The Akwesasne Museum and Community Collaboration Preserving Cultural Heritage, 1970-2012, explored how tribal museum utilized shared authority with their communities. For American Ancestors, Meaghan authored Ancestry of Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch II in 2023, and Ancestry of Douglas Brinkley in 2019. She co-authored with Chistopher C. Child, Family Tales and Trials: Settling the American South in 2020. She also contributed to Ancestors of Cokie Boggs Roberts with Kyle Hurst in 2016. She has published portable genealogists on African American Genealogy (2015) and Native Nations in New England (2020). Meaghan has authored several articles in her tenure for American Ancestors magazine including most recently, “10 Myths about Slavery in the United States.” She has presented many lectures on African American genealogy, researching enslaved ancestors, researching the history of a house, using oral history in genealogical research, researching women, and other topics.View all posts by Meaghan E.H. Siekman →