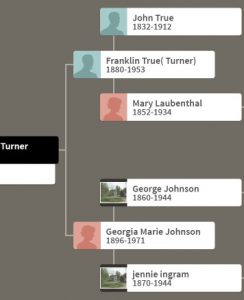

I have an entertaining update on my mysterious great-great-great-grandfather John A. Through alias True (1835–1912). In my recent post on this family, I discovered (with the help of DNA) his second later family, his slightly changed name, four additional children (a son John by each wife) – and wondered whether each of the four children he had by his two wives ever knew each other.

I have an entertaining update on my mysterious great-great-great-grandfather John A. Through alias True (1835–1912). In my recent post on this family, I discovered (with the help of DNA) his second later family, his slightly changed name, four additional children (a son John by each wife) – and wondered whether each of the four children he had by his two wives ever knew each other.

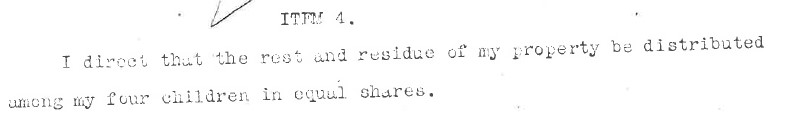

John A. True died at Fostoria, Ohio 14 January 1912 and in the index of Seneca County, Ohio Probate Records on Ancestry.com, I found that he did indeed leave a will. The year 1912 was just recent enough that I still had to write to the courthouse for copies, and I recently received John’s probate in the mail. By and large, this is a fairly ordinary probate for a person of moderate means. When it came to his will, he provided specifically for a grandson, Glenn N. True, the son of John’s son Frank True, and if that grandson died the specific bequest went to Glenn’s father Frank. John left his wife Mary all of the household furnishings. Then, when it came to the rest, he left the following item:

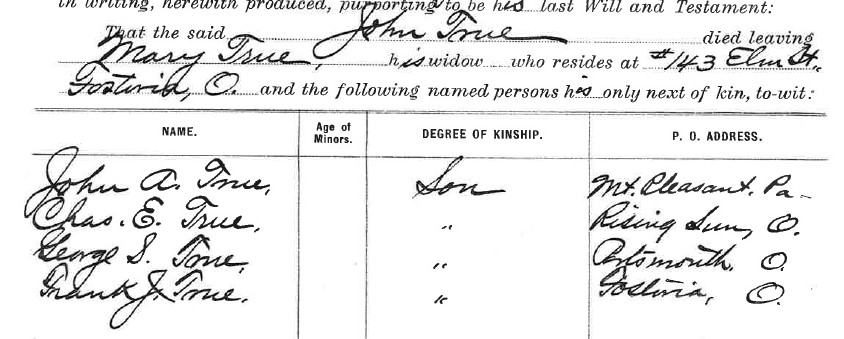

Interesting. My four children (unnamed). I think it’s fair to state the implication was the four children by his second wife, as they are listed later in a summary of heirs, as "his only next of kin, to-wit":

Except this quartet is not his only next of kin. John had four other children by his first wife; in 1912, they were alive and well and living in Philadelphia. I think it’s also safe to assume that John’s two families did not know (much if anything about) each other.

[When] you encounter ancestors who may have secret, earlier, or later families, you should not expect their probate documents to be specific or make complete sense.

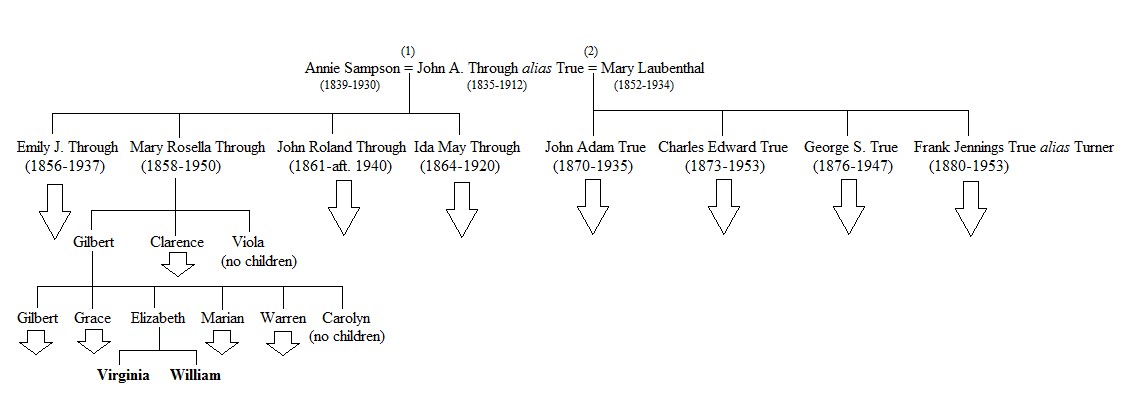

So, to the entertaining part of this. Since John left the rest of his property to his “four children” and did not name them, what does that mean from a legal standpoint? He actually had eight children. Had these four older children known of their estranged father’s death, could they have claimed something? I have no legal training, and am unfamiliar with the laws of Ohio in 1912, but let’s just have a little fun with this. Below is a chart outlining the descendants of John down to my father and his sister, indicating other children along the way who also have descendants.

The amount of John’s residuary estate was $1,525.75. If this is divided in equal eighths (rather than equal fourths), you get $190.71. From there divide this in two, then in fifths, and then again in half … and my father and his sister can each get a lovely inheritance of $9.53! (Adjusted for inflation, that’s $238.04, and who knows how much more if invested!)

Obviously all of this is absurd. I’m sure there are plenty of statutes of limitations for heirs filing such silly claims, but it does bring up the point that when you encounter ancestors who may have secret, earlier, or later families, you should not expect their probate documents to be specific or to make complete sense. Had John’s earlier children known of their estranged father’s death, this could have been an interesting court case. But the older children apparently did not know or did not care.

As one of my father’s three children, I still want my three dollars!

Share this:

About Christopher C. Child

Chris Child has worked for various departments at American Ancestors since 1997 and became a full-time employee in July 2003. He has been a member of American Ancestors since the age of eleven. He has written several articles in American Ancestors, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, and The Mayflower Descendant. He is the co-editor of The Ancestry of Catherine Middleton (American Ancestors, 2011), co-author of The Descendants of Judge John Lowell of Newburyport, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2011) and Ancestors and Descendants of George Rufus and Alice Nelson Pratt (Newbury Street Press, 2013), and author of The Nelson Family of Rowley, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2014). Chris holds a B.A. in history from Drew University in Madison, New Jersey. Areas of expertise: Southern New England, especially Connecticut; New York; ancestry of notable figures, especially presidents; genetics and genealogy; African-American and Native-American genealogy, 19th and 20th Century research, westward migrations out of New England, and applying to hereditary societies. Chris has lectured on these topics and edits the genetics and genealogy column for American Ancestors.View all posts by Christopher C. Child →