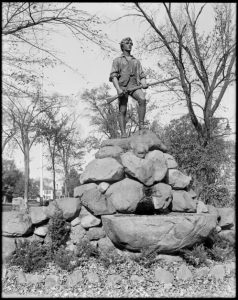

The Lexington minuteman statue, in Lexington, Massachusetts. The statue stands on the southern point of the town green. Photograph by Leon H. Abdalian. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The Lexington minuteman statue, in Lexington, Massachusetts. The statue stands on the southern point of the town green. Photograph by Leon H. Abdalian. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Patriots’ Day, a holiday unique to the State of Massachusetts, commemorates the famous skirmishes between local colonial militia and the British army in Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts, on 19 April 1775. In Lexington, the day is typically celebrated with an early morning reenactment of the skirmish on the town’s green. As an avid watcher of the reenactment, my favorite part of the event comes just prior to the skirmish. Before the fighting ensues, members of the Lexington minutemen—each representing a particular individual who was present on the green that morning—gather on the common for a roll call and commence calling their names in succession. As the roll is taken, one cannot help but notice the frequency at which similar surnames are repeated. Hearing this serves as a reminder that the men who stood on the green that April morning were not only committed to defending their town, their property, and their rights, but they were also related.

Arthur B. Tourtellot begins the first chapter of his book on the Lexington and Concord fights by observing that the group of men who gathered on Lexington common “…had some of the characteristics of a family reunion.”[1] Of the approximately 77 men who mustered on the green, six surnames were well-represented: the Harringtons, Munroes, Parkers, Tidds, Lockes, and Reeds.[2] As we will see, many of these families were also interrelated through marriage. While it is impossible within the confines of this article to outline in detail every familial connection among the members of the Lexington minutemen, two individuals are illustrative of these extended kinship networks.

Take, for instance, John Parker, captain of the Lexington minutemen. As Tourtellot goes on to explain, “At least a quarter of those present were [John Parker’s] relatives or those of his wife—cousins, nephews, brothers-in-law.”[3] In addition to the captain himself, two other Parkers were present on the green that morning: Captain John Parker’s first cousin, Jonas Parker, along with Jonas’s son, Jonas Parker, Jr.[4] Nathan Munroe, also present on the green, was the son of Captain Parker’s sister, who married Marrett Munroe.[5] Jonathan Harrington, a fifer, was the son of the captain’s widowed sister-in-law.[6]

Robert Munroe, who served as ensign for the Lexington minutemen, also had his fair share of relations on the green. His two sons, Ebenezer and John Munroe, were present along with his two sons-in-law, Daniel Harrington and William Tidd.[7] Daniel Harrington was the husband of Robert’s daughter Anna, and William Tidd was the husband of Robert’s daughter Ruth.[8]

While this shared kinship among members of the Lexington minutemen is interesting to note, it was not unique when compared with militia groups from other New England towns. Revolutionary War-era army members from Lincoln, Massachusetts, were an equally tight-knit bunch. In his study of more than 100 Lincoln soldiers who served during the Revolution, Richard C. Wiggin has discovered that “every one [was] a father/son, brother/brother-in-law, nephew/uncle, or cousin of one or more others.”[9]

One cannot help but theorize that these familial connections influenced—or, at the very least, reflected—the democratic organization of militia groups. Historians have emphasized that when the Lexington minutemen gathered on the green that morning, they did so in order to first assess, as a group, what they should do. David Hackett Fischer writes that when Capt. John Parker addressed members of the Lexington minutemen that April morning, “He did so less as their commander than as their neighbor, kinsman, and friend. These sturdy yeomen did not expect to be told what to do by anyone. They were accustomed to judge for themselves." Parker, as was customary among militia groups, had also been elected to his position, adding further to the egalitarian nature of the militia.[10]

Patriots’ Day, therefore, not only encourages me to recall the events at Lexington and Concord and the unique history of New England’s militia groups, but more importantly the individuals who participated in those famous skirmishes and the important sacrifices they made. The fact that many of the Lexington minutemen were related adds important context, and helps to bring their particular situation and struggle into sharper focus from the fog of history. Genealogy has a powerful way of reminding us that it is human beings who are the primary actors on the stage of history. Uncovering their stories (i.e., who they were, who they were related to, who they knew, what they did) can provide us with a more complete understanding and appreciation of events long past. Happy Patriots’ Day!

Notes

[1] Arthur B. Tourtellot, Lexington and Concord: The Beginning of the War of the American Revolution (New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 1963), 29.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Ibid., 29, 130.

[5] Ibid., 128.

[6] Ibid., 29.

[7] Walter R. Borneman, American Spring: Lexington, Concord, and the Road to Revolution (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2014), 152–53. See also G.W. Sampson, “Robert Munroe,” in Proceedings of the Lexington Historical Society and Papers Relating to the History of the Town (Lexington, Mass.: Published by the Historical Society, 1890), 1: 38–41.

[8] Borneman, American Spring, 152–53.

[9] Richard C. Wiggin, Embattled Farmers: Campaigns and Profiles of Revolutionary Soldiers from Lincoln, Massachusetts, 1775-1783 (Lincoln: Lincoln Historical Society, 2013), 22.

[10] David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 151, 149.

Share this:

About Dan Sousa

Dan Sousa currently serves as the Decorative Arts Trust Curatorial Intern at Historic Deerfield, Inc.—a museum in Deerfield, Massachusetts—where he is involved in several research, exhibition, and publication projects. His research interests include early American history and material culture, Massachusetts history and genealogy, Boston history and genealogy, and the history of American Catholicism. He holds a B.A. in history from Providence College and an M.A. in history from the University of Massachusetts, Boston.View all posts by Dan Sousa →