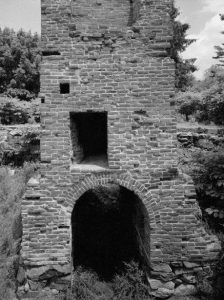

Ruins of the central chimney of the Hartwell house in Lincoln. Photo by Jet Lowe. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

Ruins of the central chimney of the Hartwell house in Lincoln. Photo by Jet Lowe. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

While perusing the shelves at a local book sale several months ago, I came across a small volume that would ultimately help to broaden my understanding of a seminal event in American history. The title of the book – Heroine of the Battle Road, Mary Flint Hartwell – caught my attention and interest. As an enthusiast of Lexington and Concord, Massachusetts history, I was familiar with the phrase “Battle Road”– likely a reference to the famous march of the British army from Boston through Lexington to seize powder and arms in Concord the night of 19 April 1775.

My suspicions were confirmed when I read the subtitle: A Drama of One Woman’s Courage on the Night of Paul Revere’s Ride in April of 1775. Having read several books on the famous skirmishes at Lexington and Concord I was curious why I had never heard of Mary Flint Hartwell. By purchasing the book, I hoped to find out more.

Heroine of the Battle Road, Mary Flint Hartwell, is not a history of the Lexington and Concord fights, but rather a short play. Written in 1995 by Palmer Faran, it tells the story of Mary Flint Hartwell—a resident of Lincoln, Massachusetts—and her activities the night of 19 April 1775.[i] The story climaxes when Mary Hartwell, having already heard the news of the approaching British army from Samuel Prescott, successfully carries this information to the captain of the Lincoln minutemen, William Smith.

As a result of her efforts, the Lincoln minutemen muster and march to Concord to meet the British.[ii] Having been taught since grade school of Paul Revere, William Dawes, and Samuel Prescott’s famous rides to alert the Massachusetts countryside—and only their efforts—the story of Mary Hartwell seemed both exceptional and unique. However, the genealogist in me asked, was Mary Hartwell’s story true and could it be supported by the documentary record?

After reading the play and its appendixes, and performing some additional research, I learned that the characters in Faran’s play—with some exceptions—are based on real individuals. The play’s main character, Mary (Flint) Hartwell, was born 22 March 1747 in Concord, Massachusetts, and was the daughter of Ephraim and Ruth Flint.[iii] She was the wife of Samuel Hartwell, who was a sergeant in the Lincoln minutemen.[iv] She died in 1846, and is buried next to her husband in Lincoln’s Old Lincoln Cemetery.[v] Samuel and Mary Hartwell’s home, in fact, can still be seen along the Battle Road within Minuteman National Historic Park—although only the original chimney of the house and a reproduction house frame still stand (see above).[vi]

While a majority of the play’s characters are based on real individuals, Faran makes clear that the story of Mary’s activities the night of April 19th has survived due in large part to oral tradition. As Faran explains in an appendix to the play, Mary Flint Hartwell is believed to have passed the story along to her grandchildren, George and Jonas Hartwell, who presumably passed the story along to their children and relatives.[vii]

Still hopeful that there might be some other proof of Mary’s heroic activities, I consulted several older and newer histories of the Lexington and Concord fights. A quick search of these texts, however, did not produce a reference to Mary Flint Hartwell.[viii] David Hackett Fischer’s book Paul Revere’s Ride does mention Mary Hartwell’s efforts, but it then cites other secondary sources.[ix] Regardless, Mary Flint Hartwell’s proximity to the route of the British army the night of April 19th, combined with the survival of said oral tradition, does allow for the story’s likelihood.

The possibility that Mary Hartwell helped to warn the local militia of the approaching British army is strengthened further by an important historical reality. As I was researching Mary Hartwell, I learned that numerous individuals—not just Revere, Dawes, and Prescott—played a role in spreading the news of the approaching British army the night of 19 April 1775.[x] Paul Revere’s alarm set in motion a complex network of riders, couriers, and town residents who spread the news of the approaching British army throughout Massachusetts.

For example, Dr. Martin Herrick of Lynnfield carried the alarm to Stoneham and Reading.[xi] Nathan Munroe and Benjamin Tidd of Lexington did the same for Bedford.[xii] Edward Bancroft carried the alarm from Acton to Groton and Pepperell.[xiii] Abel Prescott (brother of Samuel Prescott) covered Sudbury, Framingham, and Natick.[xiv] Even one African slave, Abel Benson, carried the alarm to parts of Needham.[xv] As David Hackett Fischer explains, the midnight riders also attempted to enlist the help of particular groups of local town residents: “The midnight riders went systematically about the task of engaging town leaders and military commanders of their region. They enlisted its churches and ministers, its physicians and lawyers, its family networks and voluntary associations.”[xvi] Overall, this historical context provides some supporting circumstantial evidence for the activities of Mary Flint Hartwell.

Often in genealogy we are challenged with weeding out the myths from the facts. Whether it is a story about an ancestor or something our ancestor did, we are driven to know the truth. However, as in the story of Mary Flint Hartwell, we may not always find the conclusive proof we are looking for. Despite this, my investigation reminds me that no search is ever completely unfruitful. Although we might not directly answer our research question, we might discover new information along the way that adds context to the story being researched. Information that does not definitively answer our research question, therefore, is not necessarily “bad” and should not be quickly disregarded. On the contrary, information that appears to be ancillary may provide you with a more complete picture of a particular historical scenario, and allow you to consider your research question in a new light.

Notes

[i] Palmer Faran, Heroine of the Battle Road, Mary Flint Hartwell: A Drama of One Woman’s Courage on the Night of Paul Revere’s Ride in April of 1775 (Lincoln Center, Mass.: The Cottage Press, 1995).

[ii] Faran, Heroine of the Battle Road, 8–16.

[iii] Concord, Massachusetts: Births, Marriages, and Deaths, 1635-1850 (Concord, Mass.: Printed by the Town, n.d.), 172, viewed at AmericanAncestors.org.

[iv] Richard C. Wiggin, Embattled Farmers: Campaigns and Profiles of Revolutionary Soldiers from Lincoln, Massachusetts, 1775-1783 (Lincoln, Mass.: Lincoln Historical Society, 2013), 304–6.

[v] Faran, Heroine of the Battle Road, 26–27.

[vi] Ibid., 26.

[vii] Ibid., 41.

[viii] Harold Murdock, The Nineteenth of April 1775 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company, 1925); Allen French, The Day of Lexington and Concord: The Nineteenth of April 1775 (Boston: Little, Brown, and Company, 1925); Arthur Bernon Tourtellot, Lexington and Concord: The Beginning of the War of the American Revolution (New York: W.W. Norton and Company, n.d.); Walter R. Borneman, American Spring: Lexington, Concord, and the Road to Revolution (New York: Little, Brown and Company, 2014).

[ix] David Hackett Fischer, Paul Revere’s Ride (New York: Oxford University Press, 1994), 144, 394n21.

[x] Ibid., 138–48.

[xi] Ibid., 140.

[xii] Ibid., 143.

[xiii] Ibid., 145.

[xiv] Ibid., 147.

[xv] Ibid., 147.

[xvi] Ibid., 139.

Share this:

About Dan Sousa

Dan Sousa currently serves as the Decorative Arts Trust Curatorial Intern at Historic Deerfield, Inc.—a museum in Deerfield, Massachusetts—where he is involved in several research, exhibition, and publication projects. His research interests include early American history and material culture, Massachusetts history and genealogy, Boston history and genealogy, and the history of American Catholicism. He holds a B.A. in history from Providence College and an M.A. in history from the University of Massachusetts, Boston.View all posts by Dan Sousa →