In preparing a lecture on house histories, I was reminded of the importance of chaining deeds – that is, linking the deeds for your house together using a deed chart – as the first step in researching the history of your home. Deeds are the primary source when conducting research on a building or property. While the deeds can only tell you who owned a house and not necessarily who lived in it at any given time, the transfer of the property from one owner to the next forms the structure of your research and can provide clues for where to look for more information.

In preparing a lecture on house histories, I was reminded of the importance of chaining deeds – that is, linking the deeds for your house together using a deed chart – as the first step in researching the history of your home. Deeds are the primary source when conducting research on a building or property. While the deeds can only tell you who owned a house and not necessarily who lived in it at any given time, the transfer of the property from one owner to the next forms the structure of your research and can provide clues for where to look for more information.

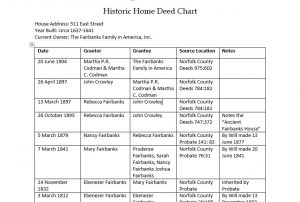

When I research a house, building, or a specific plot of land, I always like to create a deed chart as a way to chain the deeds together. Historian Marian Pierre-Louis has created some nice examples of deed charts that you can download from her blogpost, Using a Deed Chart to Trace your Deeds. The chart starts with the most recent transfer of the property to the current owners and works backward in time. If you are researching your own home, it would start with your current deed, with you as the Grantee (buyer) and the previous owner as the Grantor (seller).

Keep in mind that deeds are not for the house itself, but for the land.

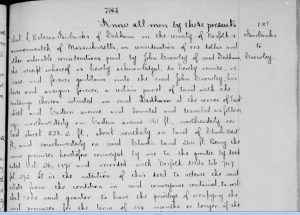

From there you can continue working backward. You know that the previous owner was at one time the grantee, so you can search the county indexes for that name as a grantee to find the next deed. Many regions have more modern deeds available online on their registry of deeds websites, though sometimes you may have to make a visit in person. You can continue to work backward in this manner to the earliest deed you can find.

Keep in mind that deeds are not for the house itself, but for the land. The earliest deed you can locate does not date the house as such, but it will reveal how long the property has been owned in a legal sense by an individual. You will likely need to rely on architectural and other clues to help date the house. Having all the deeds in place will help you determine which owner built the house based on its age.

Keep in mind that deeds are not for the house itself, but for the land. The earliest deed you can locate does not date the house as such, but it will reveal how long the property has been owned in a legal sense by an individual. You will likely need to rely on architectural and other clues to help date the house. Having all the deeds in place will help you determine which owner built the house based on its age.

Probate records are also more likely to include a description of the actual structure...

If there are gaps in your chain, check probate records. Often houses and property are left to heirs in probate rather than through a deed. You can still document this in your chart with a note that the property was transferred via probate rather than by deed. Probate records are also more likely to include a description of the actual structure rather than just the land, and the inventories included often can give you a sense of what was in the house at that date.

The reason I suggest starting a deed chain is because a deed chart forms the structure that will inform the rest of your research. Once created, it is a handy at-a-glance reference to have with you while you research. When you are digging through records and find a dated photograph of your house, having the deed chart with you will easily allow you to identify the owner of the house at the time the picture was taken. Once complete, a deed chart creates a nice timeline for the property that displays its history in its own right. You then have names and dates that can lead to further research opportunities to help you build the story of your home.

Share this:

About Meaghan E.H. Siekman

Meaghan joined the American Ancestors staff in 2013 as a Researcher before moving to the Publications team in 2018 where she is currently a Senior Genealogist of the Newbury Street Press. As a part of the Publications team, Meaghan researches and writes family histories and other scholarly projects. She also regularly develops and presents lectures as well as other educational material on a variety of research topics. Additionally, Meaghan serves as the American Ancestor's representative to the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Meaghan holds a PhD in history from Arizona State University where her focus was public history and American Indigenous history. Prior to joining American Ancestors, she worked as Curator of the Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts and as an archivist at the Heard Museum Library in Phoenix. Meaghan also worked for the National Park Service and wrote several Cultural Landscape Inventories, most notably for Victoria Mine within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Her doctoral dissertation, Weaving a New Shared Authority: The Akwesasne Museum and Community Collaboration Preserving Cultural Heritage, 1970-2012, explored how tribal museum utilized shared authority with their communities. For American Ancestors, Meaghan authored Ancestry of Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch II in 2023, and Ancestry of Douglas Brinkley in 2019. She co-authored with Chistopher C. Child, Family Tales and Trials: Settling the American South in 2020. She also contributed to Ancestors of Cokie Boggs Roberts with Kyle Hurst in 2016. She has published portable genealogists on African American Genealogy (2015) and Native Nations in New England (2020). Meaghan has authored several articles in her tenure for American Ancestors magazine including most recently, “10 Myths about Slavery in the United States.” She has presented many lectures on African American genealogy, researching enslaved ancestors, researching the history of a house, using oral history in genealogical research, researching women, and other topics.View all posts by Meaghan E.H. Siekman →