From George Peck's Wyoming: Its History, Stirring Incidents, and Romantic Adventures (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1858).

From George Peck's Wyoming: Its History, Stirring Incidents, and Romantic Adventures (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1858).

Many years ago, during a visit with my wife to her maternal grandparents, her grandfather asked if we could deliver some books which he had sold to a bookshop in Boston. He had worked on his family’s genealogy since he was a young man, beginning about 1900, and he was culling books from his library.

When we returned home I browsed through the books. One had several accounts of attacks on settlers by Indians but, not really understanding the relevance to his research, I put the book down and later in the week delivered the books as promised.

After his death some years later, we received copies of his research. Included among his papers were biographies of each of his immigrant ancestors and an excerpt from a book chronicling the history of Hanover Township and the Wyoming Valley in Pennsylvania.

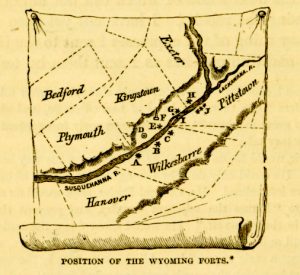

One of the settlers of Wyoming Valley was his ancestor, Elijah Inman. Elijah lost three sons as a result of the massacre on 3 July 1778; another was killed by Indians in the fall of the same year. Some estimate those killed as a result of the massacre and its aftermath at more than 300.

They were at war with Pennsylvania residents and with the British and Indians...

The most fascinating aspect to this story, however, is the sequence of events which led up to, and undoubtedly was responsible for, the massacre in 1778. The people of the Wyoming Valley, in Pennsylvania, considered themselves Connecticut citizens in a county which was created by the Connecticut legislature. They were at war with Pennsylvania residents and then with the British and Indians during the Revolution.

To understand the events leading to this situation, one needs to look back at the original charter to Plymouth Company, granted 3 November 1620 by King James I. The grant included all land "from the fortieth to the forty-sixth latitude from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean"!

By the 1700s, Connecticut was well settled and explorers were looking for new areas to colonize. Reports from the Wyoming Valley indicated that the land along the Susquehanna River was both fertile and unoccupied by white settlers. The charter of Connecticut made in March 1621 was derived from the charter to the Plymouth Company. This grant was confirmed by the King in the same year and again by Charles II in 1662. The only exception to this was New Netherland, or New York, which was occupied by the Dutch.

In 1753 the newly formed Susquehanna Company felt that, since Wyoming Valley was at the forty-first latitude, they were well within their right to found Connecticut townships there. The fact that, in about 1671, the English king granted William Penn a Pennsylvania charter which overlapped the Connecticut lands did not seem to concern the Susquehanna Company, and this unfortunate oversight became the basis for feuding between residents of the two states.

But first the Company was required to purchase the land from the Indians so that they might not come in conflict with them. To that end, in 1754 they sent a commission to Albany to meet with the great council of Six Nations. As the meeting was not secret, the governor of Pennsylvania sent a delegation to Albany in an attempt to prevent the purchase. Despite their efforts the purchase was effected. Five hundred and thirty-six purchasers were named. Most were residents of Connecticut but the group included some residents of Rhode Island, Massachusetts, New York, and Pennsylvania.

The first year proved bountiful. The soil was fertile and the crops abundant.

The French and Indian War prevented the Company from sending the settlers to the area until 1762, when about a hundred men arrived and began clearing the land for planting. The first year proved bountiful. The soil was fertile and the crops abundant. Suddenly and without warning, Indians attacked them; as the settlers were totally unprepared for such an event, 20 men were killed and the remaining settlers scattered, fleeing in disarray back to their original homes destitute of food or clothing.

It would be six years before Connecticut attempted reoccupation of the land. In this intervening period the "Pennsylvania proprietors" met with four Indian chiefs to purchase the disputed territory. In February 1769 Connecticut sent forty men back to the Wyoming Valley to be followed by 200 more. When they arrived they found the area occupied and well-fortified by the lessees of the Pennsylvania proprietors. The interlopers were arrested, then released and forced to make their way home through the wilderness without the possessions they had brought with them. At least three more times during the following years the Yankees stubbornly tried to retake the property they had purchased. With an increase of settlers, and suffering significant hardships, they were eventually successful, but not without loss of life on both sides.

The Connecticut colony in Pennsylvania prospered and grew in numbers. The Connecticut Legislative Assembly attempted to reconcile with Pennsylvania but the governor refused all of their entreaties. The Assembly then made a case for their cause and in 1773 transmitted it to four jurists in England who were famous for their knowledge of the law. Their opinion was returned unanimously in favor of the Wyoming colonists. Emboldened by this, the Connecticut General Assembly the following year established the town of Wyoming [today's Westmoreland] under the auspices of Litchfield County in Connecticut. A census was taken the following year and it was found that the town had 1,922 inhabitants.

By 1775 relations with the local Indians had again deteriorated, and war with England was looking likely. Due to the difficulties of conducting court business in Litchfield County, which was 200 miles away, in November of 1776 the Connecticut Legislature created the new county of Westmoreland for the Wyoming Valley.

This order was promptly obeyed, leaving the town almost totally defenseless.

The county decided to prepare for the possibility of war by raising a militia and building forts for protection. The new United States Congress also ordered that two companies be raised in Westmoreland County and “stationed in proper places in defense of the inhabitants.” Equipping themselves, two companies of eighty-two men each were organized and officers chosen. However, when the British took New York the two companies were ordered to join General Washington “with all possible expedition.” This order was promptly obeyed, leaving the town almost totally defenseless.

In 1777, the Indians of the Six Nations became allies of the English, putting Westmoreland County in a precarious position. Further enlistments had been made taking an additional 300 men to the war in the east, leaving only women, children, and old men to defend themselves. Applications for help to both Connecticut and Congress fell on deaf ears. An order was given by Congress for Westmoreland County to raise a company of men from their town, one supplying its own blankets, guns, and ammunition. Without men or weapons, this was an empty order. Women sent word to brothers, fathers, and husbands to return to their defense. Only about twenty officers and soldiers left their positions to return.

On about 30 June 1778 about 400 British troops, along with six or seven hundred Indians, entered the northern part of the Wyoming Valley and took one of the forts without resistance. The remaining settlers had put together a small army of 300 – mostly old men and boys. They, along with wives and children, gathered at Forty Fort on the east side of the river. A decision was made to take an offensive position and attack the British forces. While they fought bravely, the small army was vastly outnumbered and easily surrounded. Some escaped, but the majority were killed or captured; virtually all those captured were killed as well.

By his own account the British officer in charge stated that 227 scalps were taken that day and only five prisoners. Of those five, only two are known to have survived the battle.

After the massacre, those in Forty Fort had no choice but to surrender. Contrary to the promises of the British officer in command, the Indians ransacked and plundered the remaining possessions in the cabins of the women, children, and old men. Following rumors of another impending massacre, the residents once again fled the valley, some perishing from hunger and exposure. In the fall they returned to find the bodies of their neighbors still lying in the fields where they died. These were gathered up and buried in two mass graves.

[The] issue of control of the township remained.

Eventually, colonial troops disbursed the Indian encampments and drove them further west, but the issue of control of the township remained. In December of 1782 both Connecticut and Pennsylvania submitted the matter to arbitration, where it was decided that Pennsylvania had rightful claim to the territory. The settlers expected this decision and cared not what state they resided in as long as they were entitled to keep the land they had homesteaded. But the state of Pennsylvania had other plans and ordered them expelled, giving them time to leave but no compensation for their property.

Conflict was renewed, skirmishes ensued, and lives were lost on both sides. An assault by the Pennsylvanians resulted in the death of one of their own. This was the last blood shed during this long conflict. On 15 September 1784, the Legislative Assembly of Pennsylvania “ordered the settlers to be restored of their possessions.” Thus, the long and bloody disagreement over the lands in the Wyoming Valley effectively came to an end.

Sources

George Peck, Wyoming: Its History, Stirring Incidents, and Romantic Adventures (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1858)

Henry Blackman Plumb, History of Hanover Township: including Sugar Notch, Ashley and Nanticoke Boroughs: and also a History of Wyoming Valley, in Lucerne County, Pennsylvania (Wilkes-Barre, Pa.: R. Baur, 1885)

Donna Bingham Munger, Connecticut's Pennsylvania “Colony,” 1754–1810: Susquehanna Company proprietors, settlers and claimants (Westminster, Md.: Heritage Books, 2007)

Charles Miner, A History of Wyoming, in a series of letters, from Charles Miner, to his son William Penn Miner (Philadelphia: J. Crissy, 1845)

Share this:

About Tom Dreyer

Tom has a Bachelor’s degree in Business Administration from Boston University. He has been a genealogical researcher for the past thirty years. His areas of interest are New England, Nebraska, Missouri and GermanyView all posts by Tom Dreyer →