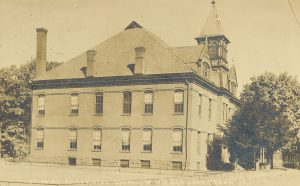

A few weeks ago, I went to one of the regular postcard shows that I frequent in the summer and came across a postcard that fills in a missing image in my family history. My entire postcard collection consists of images from Windsor Locks, Connecticut, where my Italian ancestors settled and lived for multiple generations. I have many of the mass-produced ones as well as some real photo postcards that show the flooding of the Connecticut River in 1936 and others showing houses that no longer stand.

A few weeks ago, I went to one of the regular postcard shows that I frequent in the summer and came across a postcard that fills in a missing image in my family history. My entire postcard collection consists of images from Windsor Locks, Connecticut, where my Italian ancestors settled and lived for multiple generations. I have many of the mass-produced ones as well as some real photo postcards that show the flooding of the Connecticut River in 1936 and others showing houses that no longer stand.

By the time I went to this show, I did not have any expectations about finding any new cards to add to my collection. On a whim, I decided to check the cards from Enfield, as my Scottish ancestors had settled there before moving to Ludlow. As I was flipping through all of the various views of the carpet mills in the Thompsonville section of Enfield, I paused for a second on a card that appeared out of place. Before examining the picture more closely, I could tell that it was from the 1970s, based on the color of the image and the architecture of the building, and it seemed vaguely familiar.

Upon closer examination, I discovered that it was a postcard of my grandfather’s business. I have pictures from the ribbon cutting, but this postcard is the only clear image of the entire building that I have. I told another collector, and learned that he has a real photo postcard with his grandfather with his military unit at a parade in his collection, and is hoping to find one with a better image of him. He has no idea if the card he is looking for even exists, but the nature of real photo postcards means that it could.

A real photo postcard differs from other postcards in the way that it is manufactured. Rather than being made from prints of an image, the card is a photograph that is developed on paper that can be mailed. In the early 1900s, a local amateur who enjoyed taking photographs of family, friends, or the events in their town – as well as professional photographers – could go around making postcards to use and sell. I began looking at my real photo postcards and found that I had one published by the Eastern Illustrating and Publishing Company.

Further searches revealed that in 1907, R. Herman Cassens founded the company in Maine with the goal of “Photographing the Transcontinental Trail–Maine to California” for postcards. While he was unable to reach his initial goal, he and his photographers did take more than 40,000 photographs to use as postcards between 1907 and 1947 of various scenes in New England and New York.[1]

Because of how relatively easy it was to create a real photo postcard, there could be images of your ancestor on a dusty shelf or filed away in a postcard dealer’s stock and you would not even know it. If you are looking to add more visual content to your genealogy by including images, postcards are well worth the effort to obtain. You may even find one that depicts a major aspect of an ancestor’s life.

Currently the Penobscot Marine Museum houses a bulk of the negatives that the Eastern Illustrating and Publishing Company produced and the staff are actively acquiring additional negatives as they become aware of them. Because the goal was to focus on small towns, some of these images are unique snapshots of rural New England that only exist because of the Eastern Illustrating and Publishing Company.

A list of towns that the Museum has can be found here: http://penobscotmarinemuseum.org/eastern-illustrating-publishing-company/

and information about how to help the museum acquire additional negatives can be found here:

http://penobscotmarinemuseum.org/help-us-grow-the-photography-collection/

Note

[1] See http://penobscotmarinemuseum.org/eastern-illustrating-publishing-company/

Share this:

About Jason Amos

Jason received his bachelor’s degree from the University of Connecticut and his Master of Science from Simmons College’s Graduate School of Library and Information Science, focusing in archival management. He also received a certificate in Genealogical Research from Boston University. Jason began at NEHGS as a volunteer and then as an intern with the R. Stanton Avery Special Collections before moving into Research Services. Jason enjoys writing narrative reports and searching for every piece of information relating to an ancestor that helps reveal what their life was like.View all posts by Jason Amos →