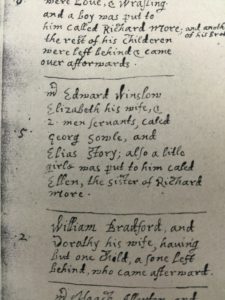

Image from Bradford’s History “of Plimoth Plantation.” From the Original Manuscript (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1928), opposite p. 531 in the Appendix.

Image from Bradford’s History “of Plimoth Plantation.” From the Original Manuscript (Boston: Wright & Potter, 1928), opposite p. 531 in the Appendix.

In 2014, I wrote a blog post about the greatness that is J.K. Rowling. My main point was that, as in your own genealogical research, a properly told story – whether fiction or non-fiction – demands a complex, well-researched treatment. Where and when were your characters born? Who were they named after? What nationality/ethnic group do your characters identify with? What is their religion or family tradition?

For most, the influence of family (both real and imagined) will play a significant role in the narrative of your story. Therefore, if you wish to tell your story in the most accurate way, it is important to research and document those who have come before you. This will help to place them into the larger narrative of their family history.

True to form, J.K. Rowling released a story this week about the founding of America’s School for Witchcraft and Wizardry, Ilvermorny, whose location was on the highest peak of Mount Greylock in the mountains of western Massachusetts. For most fans, the news was very exciting, as it was her latest addition to the magical world of Harry Potter. However, for genealogists, J.K.’s newest story fit so nicely into the known history of the founding of New England that we could hardly contain our excitement.

Here are some of the main players:

Isolt Sayre. Founder of Ilvermorny, an Irish girl from Coomloughra, County Kerry, who was born about 1603. Isolt traveled to American aboard the Mayflower posing as a male servant by the name of Elias Story (an anagram of the original name: Isolt Sayre).

Gormlaith Gaunt. Isolt’s terrible aunt, who like her Gaunt ancestors before her, believed that pure-blood witches and wizards are superior to all others, especially Muggles (non-magic people). The Gaunt line is known to be direct descendants of Salazar Slytherin, one of the four founders of Hogwarts and head of Slytherin House. Gormlaith traveled to America under the guise of William Sayre and landed in Virginia.

Chadwick and Webster Boot. Young orphaned boys, who like Isolt had magical powers. The boys were adopted by Isolt Sayre and James Steward and educated at Ilvermorny. Chadwick would grow up to marry Josephina Calderon (a Mexican Healer) and Webster returned to England, where he married a young Scottish witch.

James Steward. Early settler of Plymouth, although he did not stay in Plymouth long, as he went looking for the Boot family in the Massachusetts wilderness. After the death of Chadwick and Webster Boot’s parents, he adopted the boys and married Isolt. He was co-headmaster of Ilvermorny with his wife.

Now, most interestingly, after some quick searches of traditional seventeenth-century genealogical resources and references, I was able to identify most of the characters that J.K. Rowling used in her short story. First: yes, there was a male servant aboard the Mayflower named Elias Story; he died the first winter.[1] Second: yes, there was a record of a William Sayre who landed in Virginia aboard the Bonaventure in 1634.[2] While Rowling quickly alludes to this fact, the 1634 timeline works nicely with her essay. Third: Robert Charles Anderson identifies a James Steward as a passenger aboard the Fortune, who disappears from the written record after he is recorded in a land grant in 1621.[3] Again, Rowling does not identity the passenger ship by name, but this record would also work nicely with her short story.

The only trouble I had with verifying all of the major characters was the Boot family, as they are not included in The Great Migration Directory. I even looked for Chadwick and Webster families that were living in early New England, but only came up with some later colonists in Massachusetts Bay Colony: Charles Chadwick (1630), who arrived with the Winthrop Fleet and settled in Watertown,[4] and John Webster (1634), who settled in Ipswich.[5] I am sure I am missing something: I will have to look into this further with more time.

Nonetheless, Rowling’s attention to detail is magical.

Notes

[1] William Bradford, History of Plymouth Plantation 1620-1647 (Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society, 1912), 404.

[2] John Camden Hotten, The original lists of persons of quality: emigrants, religious exiles, political rebels, serving men sold for a term of years, apprentices, children stolen, maidens pressed, and others who went from Great Britain to the American plantations, 1600–1700 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2012), 35.

[3] Robert Charles Anderson, The Great Migration Directory (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2015), 320.

[4] Anderson, The Great Migration Directory, 59.

[5] Ibid, 363.

Share this:

About Lindsay Fulton

Lindsay Fulton is a nationally recognized professional genealogist and lecturer who joined American Ancestors in 2012. She leads the Research and Library Services team as Chief Research Officer, as well as the research team working on 10 Million Names. In addition to helping constituents with their research, Lindsay has authored a Portable Genealogists on the topics of Applying to Lineage Societies and the United States Federal Census (1790-1950), and is a frequent contributor to the American Ancestors blog, Vita-Brevis. She was featured in the Emmy-Winning Program: Finding your Roots: The Seedlings, a web series inspired by the PBS series “Finding Your Roots with Henry Louis Gates, Jr.", as well as another popular PBS series, “Samantha Brown’s Places to Love.” Before, American Ancestors, Lindsay worked at the National Archives and Records Administration in Waltham, Massachusetts, where she designed and implemented an original curriculum program exploring the Chinese Exclusion Era for elementary school students. She holds a B.A. from Merrimack College and M.A. from the University of Massachusetts-Boston. Area of Expertise: State and Federal Censuses, New England, Ireland, and New York research, with a focus on research methodology and organization. Lindsay also oversees the research team working on the 10 Million Names project.View all posts by Lindsay Fulton →