You’ve probably heard the story: “My ancestor’s name was changed at Ellis Island!” But you also probably know that this is a myth; immigration officials at Ellis Island did not randomly alter incoming passengers’ names. However, the surnames and given names of one group of immigrants, French-Canadians, frequently did change when our ancestors crossed the border.

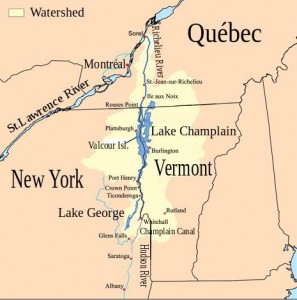

Throughout the centuries, migration from Quebec was driven by poor agricultural conditions, overpopulation, and inadequate employment opportunities. Settlers typically came down the Richelieu Valley into the United States, choosing to try their fortunes in Vermont or northern New York (see Figure 1)[1]. When they began to put down roots and buy land, get married, and baptize children, their names as recorded by clerks and priests morphed into something different. The examples below, from nineteenth-century century Vermont, illustrate what happened.

First, English-speaking clerks or priests wrote the French name phonetically, according to English rules of pronunciation. Most settlers at the time were illiterate and wouldn’t have known if their names had been captured accurately. Thus, the French surname “Bousquet” could become “Bostwick,” Chouquette “Shackett,” and Michaud “Mitchell.”

Second, clerks or clergy could translate the French name into its English equivalent: e.g., Lenoir becomes “Black,” Roi becomes “King.”

Third, confusion about “dit” names could lead English speakers to choose (and Anglicize) one or the other of a Quebecois family names as the American surname. For example, Homand dit Francoeur sometimes became “Francoeur” (my family) and sometimes became “Oman.”

Finally, there is the occasional name change that doesn’t fall into any of the above categories. My personal brick wall was the given name recorded by a Vermont clerk of “Nelson.” What was his name prior to emigration? I couldn’t find a candidate Nelson in any French-Canadian records. Thanks to the Gassette book mentioned below, I learned that “Nelson” was “Narcisse” in Quebec records. Who knew?

Three helpful sources will assist family historians seeking their French-Canadian ancestors. The American-French Genealogical Society has an online list of French-Canadian Surnames and possible variants in the United States.[2] Véronique Gassette has published a spiral-bound book, "French-Canadian Names: Vermont Variants, through the Vermont Genealogical Society. Finally, RootsWeb hosts a list of “dit” names typically associated with a specific family name.[3]

Notes

[1] “Richelieu River,” accessed at Wikepedia (https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richelieu_River 23 March 2016, citing Champlainmap.png: Kmusserderivative work: Pierre_cb - Champlainmap.png, CC BY-SA 2.5.

[2] American-French Genealogical Society, “French-Canadian Surnames: Variants, Dit, Anglicizations, etc.,” accessed 23 March 2016.

[3] http://freepages.genealogy.rootsweb.ancestry.com/~unclefred/DitNames.html, accessed 23 March 2016.

Share this:

About Ann Lawthers

Ann G. Lawthers assists our library patrons in enhancing their research skills and in bringing alive their family histories. She is a graduate of Wellesley College, the Harvard School of Public Health and has completed the Boston University Certificate in Genealogical Research program. She has conducted genealogical projects as an independent researcher. Ann is familiar with resources for Massachusetts, Vermont, Pennsylvania, Maryland, New Jersey; and has research experience with Quebec and the Canadian Atlantic Provinces, Ireland and Germany.View all posts by Ann Lawthers →