As anyone engaged in the study of family history knows, researching the women of the past can be a difficult process. Many commonly used sources draw out details in the lives of men but provide only minimal statistical information about the lives of women. Women are often erased from the narratives written by historians and their documents lost or destroyed. This state of affairs is changing, however, and improving, thanks in part to the entrance into the historical field of women eager to tell their own stories. This substantial increase in historical work by women began in part with the field of genealogy, which opened to women much more quickly than other areas of study.

This brings me to some research I have been doing lately in the institutional archives at NEHGS. My coworkers and I were recently discussing a set of ambrotypes in our collection which show an early class of members of NEHGS (exclusively men, unsurprisingly for the year 1858), and that got me wondering about the first women admitted to the Society. As I’ve since found out, NEHGS first accepted women as members in the year 1898, 40 years after those ambrotypes were produced and 53 years after the Society’s founding.

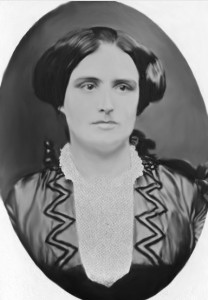

In order to make this possible, a majority of the current members had to agree to make a change to the charter (which originally specified that only men could be members) and then submit this change for consideration by the Massachusetts State Legislature, who at the time had to approve any changes to charters the body had granted. Once this change was accepted, 36 women were nominated for membership and 29 accepted. Their membership applications are full of interesting details, including a number of women who record their profession as “Genealogist.” But by far my favorite find in this first group was the application of Harriet Hanson Robinson, noted author and suffragist.

Harriet’s involvement in NEHGS actually extends back quite a bit before she was admitted to the Society. A prolific writer throughout her life, Harriet contributed several articles to the Register in the 1880s and early 1890s. She also wrote a number of books, and in fact donated her book on women’s suffrage nearly fifteen years before she was actually allowed to be a member. Knowing all this, it is no surprise that she was elected to membership as soon as she was eligible.

Harriet is a great example of the vital work women were doing in this period to preserve history that might otherwise have been lost. Two of her publications are particularly noteworthy on this front: Loom and Spindle, a record of her time working in the cotton mills in Lowell, and Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement, a record of women’s rights activism from 1774–1881. While she is concerned more broadly with the way early reformers can be forgotten by the time their goals are achieved (she calls the reformer “the Rip Van Winkle in the history of his time”), one particular story stands out to me as an example of how she saw women preserved in history and what she was trying to change.

In her book on the woman suffrage movement, she talks about Abby Folsom, an early activist who was deemed insane by her contemporaries and by history. Harriet notes that “[Ralph Waldo] Emerson called her the ‘Flea of Conventions’ [and] but for this impaling on the pen of his genius, her name would have been long ago lost in her forgotten grave.” This is not the fate she wants for the women of her generation or for herself – to be forgotten, or only remembered (perhaps negatively) in the words of notable men.

As a woman studying history, I feel something like kinship to the women like Harriet who came before me, and I look forward to seeing how we can all continue her legacy in the field of genealogy.

Note

Quotations from Harriet Jane Hanson Robinson, Massachusetts in the Woman Suffrage Movement. A General; Political, Legal and Legislative History from 1774 to 1881 (Boston: Roberts Bros., 1881), ix and 11.

Share this:

About Jennifer Guerin

Jennifer has a BA in History and American Studies from Smith College, and has previous non-profit experience at the Smith College Museum of Art, the Toledo Museum of Art, and the Smithsonian National Museum of American History. While working at the Smithsonian, she developed a love of genealogy while researching collections of family papers and transcribing oral histories. Jennifer’s primary historical interest is Revolutionary history, particularly the experiences of everyday people during revolutionary periods. She is also passionate about food culture and popular music of the past and the present.View all posts by Jennifer Guerin →