Douglas Richardson’s Magna Carta Ancestry isn’t a particularly old or rare volume, but it is a frequently used resource in our collections. This massive reference book tracks family lines between medieval England and colonial America, making it a valuable source of information for researchers. Unfortunately, as our conservation technician Deborah Rossi discovered, the original binding of this book was too weak to support such frequent use. To help understand why, here’s some book anatomy 101:

Douglas Richardson’s Magna Carta Ancestry isn’t a particularly old or rare volume, but it is a frequently used resource in our collections. This massive reference book tracks family lines between medieval England and colonial America, making it a valuable source of information for researchers. Unfortunately, as our conservation technician Deborah Rossi discovered, the original binding of this book was too weak to support such frequent use. To help understand why, here’s some book anatomy 101:

A standard case book binding is made up of two major parts, the case and the textblock. The case refers to the front and back cover boards and the spine, while the textblock refers to the paper making up the book itself. Binding styles from earlier eras incorporated these elements together, but in modern bookbinding, standard practice is to sew the textblock first and attach the case at the end of the process. The problem with the binding of the Magna Carta Ancestry is a common problem with mass-produced books, and has to do with the weak attachment between the case and the textblock.

As you may have noticed, in most books, the textblock includes extra blank pages at the front and back known as endpapers. In a case binding, the outermost endpapers are pasted down onto the inside front and back cover boards, making for a weak attachment between the case and the textblock. In strongly bound books, the binding will include sturdy cloth hinges beneath the endpapers. In the case of the Magna Carta Ancestry, however, there were no cloth hinges, and the lack contributed to the eventual failure of the binding.

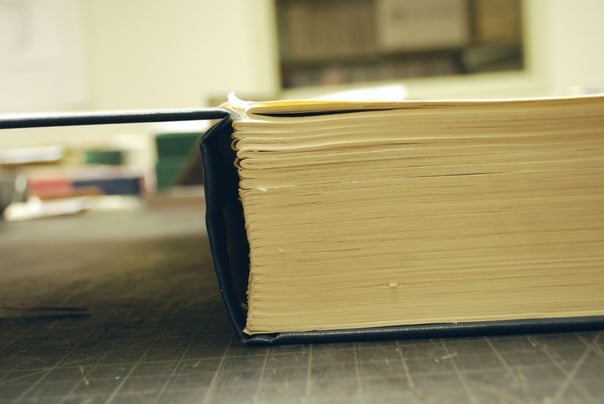

The other contributing problem was bullnosing, an effect which often occurs in large flat-back spines—you’ve probably seen it on large telephone books. Over time, the flat spine begins to break or curve back upon itself, and the outer edge of the book becomes a convex curve. When this happens in a case-bound book, the spine will begin to pull away from the case, as you can see in the above picture. When this is added to the lack of cloth hinges, it was inevitable that the case would fall off completely after heavy use.

So, what can be done to fix this?

Because the Magna Carta Ancestry is such a frequently used book, and investing in a new copy would only replicate the same problems down the road, Deborah decided to deconstruct our copy entirely and create a sturdy split-board binding. This involved three major steps:

- Re-sew the textblock with added cloth hinges.

- Create a rounded-back spine which will resist bullnosing.

- Reattach the case with the new hinges glued between the split-board binding.

Because the textblock had become so bullnosed, the spine needed to be taken apart and re-sewn entirely. A heavy layer of glue was carefully removed, and the original stitching was cut to separate the textblock into individual sections. Blue cloth, chosen to match the original cloth of the book cover, was added to the outer edge of the first and last section.

Because the textblock had become so bullnosed, the spine needed to be taken apart and re-sewn entirely. A heavy layer of glue was carefully removed, and the original stitching was cut to separate the textblock into individual sections. Blue cloth, chosen to match the original cloth of the book cover, was added to the outer edge of the first and last section.

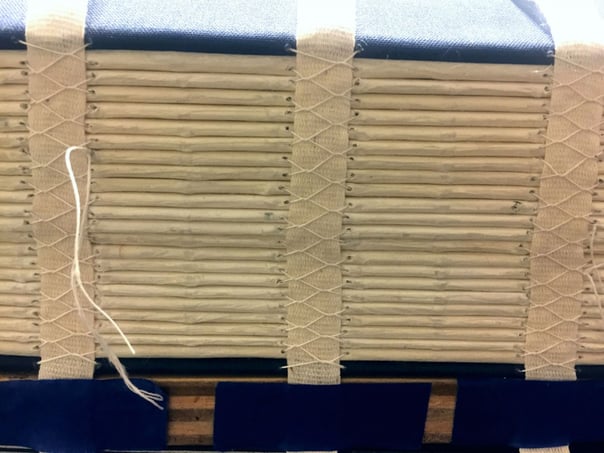

The spine was then resewn, with cloth hinges added in the form of cotton tapes running beneath the stitches.

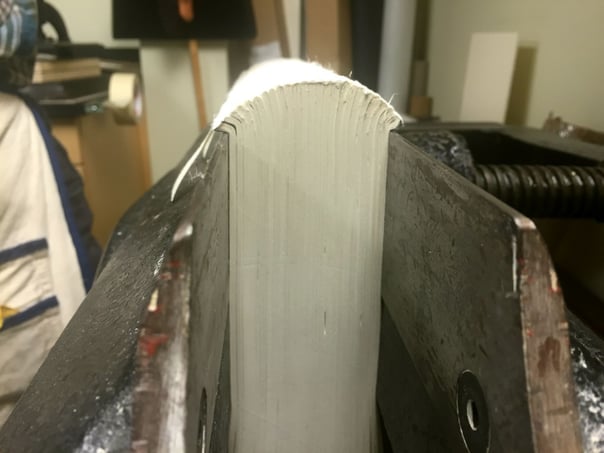

Once sewn, the textblock was braced in a large clamp-like tool, known by bookbinders as a job backer. The jaws of the job backer are opened to the width of the foredge of the book, but as the textblock is lowered into the tool, the thickness of the spine prevents it from passing all the way through due to the folds of the sections and the added thickness of the thread. A backing hammer is then used to strike the sections until they fan out, creating a rounded convex curve as you can see in the next picture.

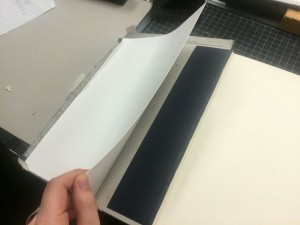

Once done, the final step is to reattach the case and create the split-board binding. In a split-board binding, the cloth hinges at the front and back of the textblock are each sandwiched between two boards: in this case, the cover boards from the original binding, and additional thinner boards lying close to the textblock. This creates a strong binding which is very difficult to detach, even with frequent use.

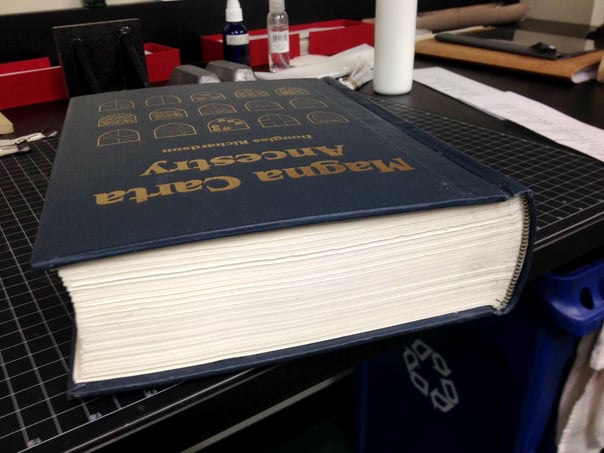

Now that the book is cased in, it can be returned to the stacks, ready to be used and referenced again.

Now that the book is cased in, it can be returned to the stacks, ready to be used and referenced again.

The rebinding of the Magna Carta Ancestry is just one example of how we maintain and strengthen our library’s collections in the conservation lab every day. Our goal, whether it’s preserving a rare and valuable document or maintaining a frequently used book, is to make sure our resources are sturdy enough to stand the test of time and continue to benefit researchers for years to come.

Share this:

About Thomas Grebenchick

Thomas Grebenchick was responsible for managing and updating existing web content, creating new content, and assisting in digital communications and strategy. Originally from Massachusetts, he holds a B.A. in English from Brandeis University, and has experience in copywriting, web and digital design, and social media marketing.View all posts by Thomas Grebenchick →