A squirrel![1] I find a lot of them while researching and I am sure all other researchers find them, too: those pieces of information that have nothing to do with what you are researching. You come across them by accident and they pull your attention away from what you are trying to find because they are equally or sometimes more interesting. Sometimes it is a quick tangent – and sometimes squirrels can lead to an entirely new path of research that sticks with you for a long time.

A squirrel![1] I find a lot of them while researching and I am sure all other researchers find them, too: those pieces of information that have nothing to do with what you are researching. You come across them by accident and they pull your attention away from what you are trying to find because they are equally or sometimes more interesting. Sometimes it is a quick tangent – and sometimes squirrels can lead to an entirely new path of research that sticks with you for a long time.

My most recent squirrel diverted me while I was searching Plymouth County, Massachusetts probate records. While going through the index I spotted a notation for a record dating to 1719 which indicated that the person was “Indian.” I have always had an interest in American Indian history, and this seemed like an early probate for someone identified as being American Indian, so I just had to learn more.

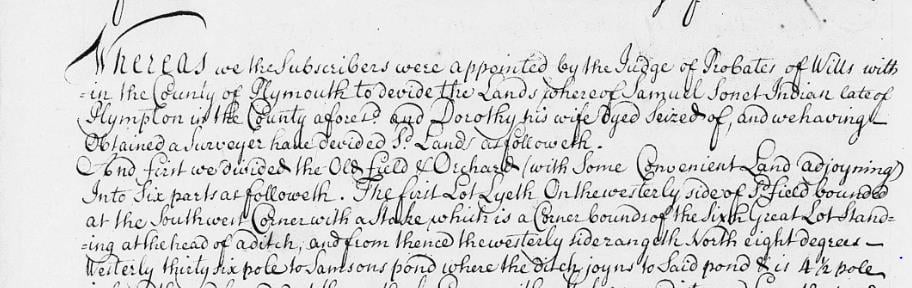

The record was a division of the estate of Samuel Sonet.[2] His land was divided into six lots, and the decree gives the names of his five children, each of whom inherited one of the lots. I then searched the Massachusetts Vital Records before 1850 database on AmericanAncestors.org and located some vital records for the family, which also indicated that they were American Indian. The marriage records I found provided some other related surnames. Before I knew it, I was creating a family tree for an early eighteenth-century Native family in Plymouth, Massachusetts.

I then became curious about how many other records we might have – on the variety of databases available through AmericanAncestors.org – that would indicate individuals were American Indian. After testing out a few search options, I discovered that searching for the term “Indian” in the “Keyword” search or the “Surname” search would yield results, since often the term “Indian” was used as a surname if individuals were Native. Using an advanced search option, you can then limit results to specific geographic locations, periods of time, or in specific collections.

Of course, the searches do not include records where the term “Indian” was not prominent in the person’s name or evident from the cover pages of the document. However, this type of search is a good starting point if you are trying to identify American Indian families in our collections. Perhaps as more documents concerning American Indians are identified, the search results will include even those records where the fact that they concern Natives is not as evident. The best part is that the results usually contain clues that can lead you to more relatives and others that may be American Indian.

In Research Services we often have clients asking us to find their American Indian ancestors. While this approach is working in the opposite direction (tracing families forward instead of back), it may help to identify American Indians in a particular region and time that could be related to an individual’s potential Indian ancestors. The only danger with this approach to research is it is more likely to send you down another path, chasing another squirrel, to some fascinating family stories.

Notes

[1] See the Disney/Pixar film Up (2009).

[2] Samuel Sonet (Indian), division of estate (25 July 1719), Plymouth County, Massachusetts Probate Records, Volume 4, Page 182. As found on FamilySearch.org.

Share this:

About Meaghan E.H. Siekman

Meaghan joined the American Ancestors staff in 2013 as a Researcher before moving to the Publications team in 2018 where she is currently a Senior Genealogist of the Newbury Street Press. As a part of the Publications team, Meaghan researches and writes family histories and other scholarly projects. She also regularly develops and presents lectures as well as other educational material on a variety of research topics. Additionally, Meaghan serves as the American Ancestor's representative to the New England Regional Fellowship Consortium. Meaghan holds a PhD in history from Arizona State University where her focus was public history and American Indigenous history. Prior to joining American Ancestors, she worked as Curator of the Fairbanks House in Dedham, Massachusetts and as an archivist at the Heard Museum Library in Phoenix. Meaghan also worked for the National Park Service and wrote several Cultural Landscape Inventories, most notably for Victoria Mine within the Organ Pipe Cactus National Monument. Her doctoral dissertation, Weaving a New Shared Authority: The Akwesasne Museum and Community Collaboration Preserving Cultural Heritage, 1970-2012, explored how tribal museum utilized shared authority with their communities. For American Ancestors, Meaghan authored Ancestry of Secretary Lonnie G. Bunch II in 2023, and Ancestry of Douglas Brinkley in 2019. She co-authored with Chistopher C. Child, Family Tales and Trials: Settling the American South in 2020. She also contributed to Ancestors of Cokie Boggs Roberts with Kyle Hurst in 2016. She has published portable genealogists on African American Genealogy (2015) and Native Nations in New England (2020). Meaghan has authored several articles in her tenure for American Ancestors magazine including most recently, “10 Myths about Slavery in the United States.” She has presented many lectures on African American genealogy, researching enslaved ancestors, researching the history of a house, using oral history in genealogical research, researching women, and other topics.View all posts by Meaghan E.H. Siekman →