One of the resources every family historian hopes to find and treasure is a family Bible full of handwritten notations of births, marriages, and deaths. These Bibles are often beautiful in themselves for their illuminated pages, or for the well-worn leather covers molded by devoted hands. Not to be overlooked, however, are the enclosures some owners pressed between those pages, enclosures which might yield some of the basic data always sought, and which might also give insight into the owners’ personalities and the events of their daily lives.

One of the resources every family historian hopes to find and treasure is a family Bible full of handwritten notations of births, marriages, and deaths. These Bibles are often beautiful in themselves for their illuminated pages, or for the well-worn leather covers molded by devoted hands. Not to be overlooked, however, are the enclosures some owners pressed between those pages, enclosures which might yield some of the basic data always sought, and which might also give insight into the owners’ personalities and the events of their daily lives.

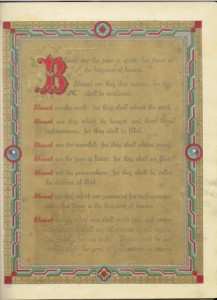

While many researchers are thrilled to have one such Bible, I found myself with five, including my great-grandmother Felicia Lee’s fifteen pounder which she carried with her until her death in 1952 at age 97. Her huge Bible with its illuminated front page also contained Certificates of Excellence for her second son, Robert Edward Lee; a corsage of dried flowers; and even a notation of her husband’s second marriage in 1918 (but no notation of their divorce). Felicia recorded every birth, marriage, and death in her Bible, and other family members continued the effort even after her death.

While many researchers are thrilled to have one such Bible, I found myself with five, including my great-grandmother Felicia Lee’s fifteen pounder which she carried with her until her death in 1952 at age 97. Her huge Bible with its illuminated front page also contained Certificates of Excellence for her second son, Robert Edward Lee; a corsage of dried flowers; and even a notation of her husband’s second marriage in 1918 (but no notation of their divorce). Felicia recorded every birth, marriage, and death in her Bible, and other family members continued the effort even after her death.

Great-great-grandmother Mary Ann Stone Cony (1840–1927) left her Bible so well-worn it is almost spine-less, filled with not only vital records but also newspaper clippings, notes from grandchildren (in childish pencil-scrawls), and even fabric scraps. The newspaper clippings report deaths of friends and family (e.g., the death in 1886 of my great-great-great-grandmother Experience Read Cony, who was delivered by midwife Martha Ballard in 1802), weddings, anniversaries, and “Recipes of New England Housewives.” The fabric scraps were still of strong colors and fascinated me because I realized Mary Ann was wearing a dress of that plaid in one of her tintypes. Married to Charles Otis Cony in 1861, this might have been her wedding dress.

Great-great-grandmother Mary Ann Stone Cony (1840–1927) left her Bible so well-worn it is almost spine-less, filled with not only vital records but also newspaper clippings, notes from grandchildren (in childish pencil-scrawls), and even fabric scraps. The newspaper clippings report deaths of friends and family (e.g., the death in 1886 of my great-great-great-grandmother Experience Read Cony, who was delivered by midwife Martha Ballard in 1802), weddings, anniversaries, and “Recipes of New England Housewives.” The fabric scraps were still of strong colors and fascinated me because I realized Mary Ann was wearing a dress of that plaid in one of her tintypes. Married to Charles Otis Cony in 1861, this might have been her wedding dress.

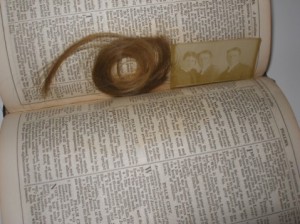

Great-great-grandmother Mary Helen Sawtelle Church gave her son Ambrose (1861–1896) a small Bible on March 18, 1880 (perhaps it was an Easter gift, which was on March 28th), inscribing Scriptures for his inspiration. Only sixteen years later she would include his obituary in the same Bible, and pressed between its pages is a lock of his hair along with a tintype of Ambrose with his brother George (1859–1890) and Ambrose’s son Rex. Ambrose’s wife Ellen Frances Cony Church treasured the Bible, eventually passing it on to their son and grandson.

Great-great-grandmother Mary Helen Sawtelle Church gave her son Ambrose (1861–1896) a small Bible on March 18, 1880 (perhaps it was an Easter gift, which was on March 28th), inscribing Scriptures for his inspiration. Only sixteen years later she would include his obituary in the same Bible, and pressed between its pages is a lock of his hair along with a tintype of Ambrose with his brother George (1859–1890) and Ambrose’s son Rex. Ambrose’s wife Ellen Frances Cony Church treasured the Bible, eventually passing it on to their son and grandson.

This Ambrose Church’s great-grandfather’s Bible provided me with an almost complete outline of that line of the Church family on multiple pages from John (1709–1806) and Amy Winter Church (1711–1815) to my grandfather Rex Otis Church (1883–1956). The Bible, printed in 1827, even included a Table of Scripture Measures: in dry measure, The Lethech is half of a Homer. Got that?

This Ambrose Church’s great-grandfather’s Bible provided me with an almost complete outline of that line of the Church family on multiple pages from John (1709–1806) and Amy Winter Church (1711–1815) to my grandfather Rex Otis Church (1883–1956). The Bible, printed in 1827, even included a Table of Scripture Measures: in dry measure, The Lethech is half of a Homer. Got that?

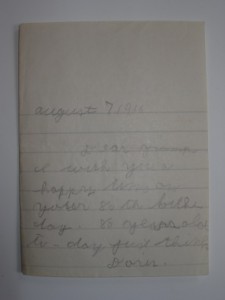

Family Bibles can contain all sorts of information about ancestors as well as their contemporaries. I’ve read an article detailing the Lincoln autopsy printed almost thirty years afterward, and one about Mrs. M.L. Baldwin, a member of the Chippewa Tribe who was a claims adjuster in Washington, D.C. Important genealogical clues can be found in the most unexpected places: a birthday wish from my Aunt Doris to her great-grandfather Charles Otis Cony (1836–1924), for instance. Written in her best nine-year-old hand, the darling confirmed my great-great grandfather’s birth year by dating her note and stating his age!

Family Bibles can contain all sorts of information about ancestors as well as their contemporaries. I’ve read an article detailing the Lincoln autopsy printed almost thirty years afterward, and one about Mrs. M.L. Baldwin, a member of the Chippewa Tribe who was a claims adjuster in Washington, D.C. Important genealogical clues can be found in the most unexpected places: a birthday wish from my Aunt Doris to her great-grandfather Charles Otis Cony (1836–1924), for instance. Written in her best nine-year-old hand, the darling confirmed my great-great grandfather’s birth year by dating her note and stating his age!

Share this:

About Jan Doerr

Jan Doerr received a B.A. degree in Sociology/Secondary Education from the University of New Hampshire, and spent a long career in the legal profession while researching her family history. She has recently written and published articles for WBUR.org’s Cognoscenti blog: “Labor of Love: Preserving a 226-Year-Old Family Home and Preparing to Let It Go” and “The Value of Family Heirlooms in a Digital Age.” Jan currently lives with her attorney husband in Augusta, Maine, where she serves two Siamese cats and spends all her retirement money propping up a really old house.View all posts by Jan Doerr →