This is part two of a series on digitizing our special collections. Click here to read the first post.

Before we send some of the items from our R. Stanton Avery Special Collections to third parties for scanning, there is work we must do to make this digitization possible. Sally Benny, Curator of Digital Collections, is in charge of organizing and preparing the collections before they are sent to the scanner.

The first step is choosing which items to prioritize, particularly for the Civil War collections. Of the five collections in this pilot program, we chose to start with the Chapman Family Correspondence. This is one of the smaller collections, both in terms of the number of items and the physical size of the items themselves. The scanning service we’ve chosen has equipment that can accommodate larger items, but most of our items will fit on the standard-sized scanner. The larger items will be digitized separately and may take longer to complete. We want to start with a smaller collection to test how quickly the scanning can be done, and to learn what we can expect as the process moves forward.

Once we choose which collections to send first, it’s time to organize those collections and create a finding aid, if one does not exist already. Sally Benny does this with help from NEHGS volunteers. The collections are organized in a system of manila folders and filed into boxes. Some collections, like the Chapman correspondence, fit neatly into one box; others may require many more. The finding aid is based on this system; it lists every folder, gives basic information about the contents, and says which box and folder it can be found in.

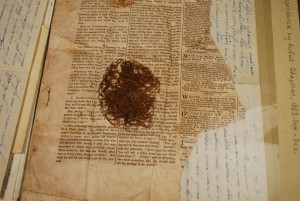

The next step is to prepare each item to be handled by the scanning staff. Some items require special instructions for handling or scanning. For example, if a document has blank pages, we don’t need to scan images of blank paper, so we add instructions to skip those particular pages. In other cases, an item may be fragile or fall apart easily, so we put it in a transparent polyester-film pocket and instruct the scanner operator not to remove it when scanning. This was the case for one interesting item in the Chapman correspondence, shown above.

This mysterious material was found wrapped in a torn piece of newspaper and included with one of Rufus Chapman’s letters to his wife, Catherine. For the sake of digitization, we flattened out the newspaper, and saved the whole thing in a polyester-film pocket. Once the collection is available online, maybe a keen researcher will be able to tell us what this is!

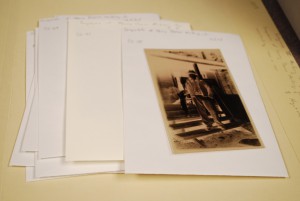

Sometimes unexpected tasks arise in this process, as they did with the Frederick W. Hill Family Photographs. This is a huge collection of nearly 900 prints and 1,100 negatives, and the negatives will be scanned along with the prints. Each negative now needs to be stored in its own individual envelope, before being stored as a group in the larger manila folders, so that each negative can be assigned a unique, identifying number. In the process of preparing the collection, we discovered that the extra envelopes for the negatives added enough thickness that the collection would no longer fit into the eight allotted boxes. Not only did the boxes need to be reorganized, but the finding aid had to be updated to accurately reflect the collection’s organization.

Sometimes unexpected tasks arise in this process, as they did with the Frederick W. Hill Family Photographs. This is a huge collection of nearly 900 prints and 1,100 negatives, and the negatives will be scanned along with the prints. Each negative now needs to be stored in its own individual envelope, before being stored as a group in the larger manila folders, so that each negative can be assigned a unique, identifying number. In the process of preparing the collection, we discovered that the extra envelopes for the negatives added enough thickness that the collection would no longer fit into the eight allotted boxes. Not only did the boxes need to be reorganized, but the finding aid had to be updated to accurately reflect the collection’s organization.

Now that our first collections have been prepared, it’s time to send them off to be scanned. The scanners will use our finding aids, with the basic information about each item, to create metadata for the scanned images. When we get the files back, this will make it easy for us to sort and organize the files – and the next step will be up to us.

Continued here.

Share this:

About Thomas Grebenchick

Thomas Grebenchick was responsible for managing and updating existing web content, creating new content, and assisting in digital communications and strategy. Originally from Massachusetts, he holds a B.A. in English from Brandeis University, and has experience in copywriting, web and digital design, and social media marketing.View all posts by Thomas Grebenchick →