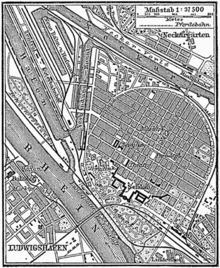

Map of Mannheim in 1888. (Note the circular grid at right, representing the city William Boucher Jr. would have known.)

Map of Mannheim in 1888. (Note the circular grid at right, representing the city William Boucher Jr. would have known.)

My great-grandmother was one of a large family, and when her mother died in 1924 the family house was evidently broken up, its contents divided between Wally and her nine surviving brothers and sisters. A fascinating family register, listing my great-great-grandfather’s twenty-three children and (most of) their birthdates descended to the youngest daughter: her granddaughter, my second cousin once removed, now has it. My great-grandmother Wally received a curious trove of documents associated with her father, a well-known musical instrument-maker: her portion included an 1845 passport from the Grand Duchy of Baden, an 1863 receipt for a soldier substitute, and an 1899 condolence letter from William Boucher Jr.’s half-brother to his widow.

These papers descended to my grandmother, to my mother, and then to me. They are like Brigadoon, though, as I’ve had them, misplaced them, had them, and (for now) misplaced them again. They are almost certainly lurking on a bookshelf in my apartment … but which one?

The passport would be nice to find, as it would settle a current argument. When registering the births of a number of his children, William Boucher Jr. (1822–1899) listed his birthplace as the City of Hanover in the then-Kingdom of Hanover, since 1871 a part of Germany. This conflicts with the passport, which states that he was born in Bielefeld, a suburb of Mannheim, in Baden.

Based on this information, in 1981 I visited Mannheim and found my way to the City Archives, where I had an awkward but ultimately successful talk with the archivist in my fractured high school German. He found my great-great-great-grandparents’ 1822 marriage and the birth, later on that year, of my great-great-grandfather in Bielefeld. The passport was issued so that he could join his father and stepmother in Baltimore, Maryland. In 1850, he returned to Baden to help settle the estate of his maternal grandmother, Johanna Elisabeth (Hoffmann) Förstner, and the passport reflects his arrival in Mannheim.

And why do these papers – very much desired by museum curators with an interest in William Boucher Jr.’s career – keep slipping through my fingers? The reasons, I suspect, will be familiar ones: I graduated from high school in the same year that my mother abruptly moved from Florida to Massachusetts, at which point the Boucher papers disappeared into the chaos of the move. They then resurfaced when my mother died, and I carefully had them conserved. They returned from North Andover in pristine shape, and I set them reverently down … somewhere … and now I can’t find them!

All of which will be a familiar tale to genealogists and non-genealogists alike. The Boucher papers are my version of lost car-keys, or – as I would prefer to think – Brigadoon, and one day soon they will turn up (and be scanned at once – a story for another day, I hope!).

Share this:

About Scott C. Steward

Scott C. Steward has been NEHGS’ Editor-in-Chief since 2013. He is the author, co-author, or editor of genealogies of the Ayer, Le Roy, Lowell, Saltonstall, Thorndike, and Winthrop families. His articles have appeared in The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, NEXUS, New England Ancestors, American Ancestors, and The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, and he has written book reviews for the Register, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, and the National Genealogical Society Quarterly.View all posts by Scott C. Steward →