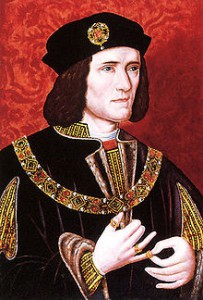

I wrote in American Ancestors last year about the fascinating discovery of the remains of King Richard III in a Leicestershire parking lot, and the use of mtDNA via matrilineal relatives over many generations to get a positive match. Now, in another twist to this story, comes the publication of Richard III’s Y-DNA results, published in Nature on 2 December 2014 – a second and more detailed genealogical chart appears in the Telegraph.

I wrote in American Ancestors last year about the fascinating discovery of the remains of King Richard III in a Leicestershire parking lot, and the use of mtDNA via matrilineal relatives over many generations to get a positive match. Now, in another twist to this story, comes the publication of Richard III’s Y-DNA results, published in Nature on 2 December 2014 – a second and more detailed genealogical chart appears in the Telegraph.

The gist of the story regarding the Y-DNA is that Richard III [haplogroup G-P287] did not share the same Y-DNA as four of the five documented descendants of Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort [haplogroup R1b-U152], descended from Richard’s great-great-grandfather King Edward III (1312–1377), with some commentary on how this could affect claims to the crown during the War of the Roses.

Solid conclusions from this Y-DNA report:

1) Richard III, King of England (1452–1485) has the Y-DNA of G-P287 (based on his human remains);

2) Henry Somerset, 5th Duke of Beaufort (1744–1803) has the Y-DNA of R1b-U152 (based on the Y-DNA of four of his five documented male line descendants through two different sons); and, thus,

3) The 5th Duke of Beaufort and King Richard III cannot be patrilineally related, as the paper evidence would indicate.

Where the break could have occurred:

There are 16 generations between the 5th Duke of Beaufort and Edward III, and five generations between Richard III and Edward III. There are four opportunities between Richard III and Edward III for a false-paternity event, and fifteen between Edward III and the Duke of Beaufort, for a total of nineteen possibilities for a false-paternity event. (For the generation of John of Gaunt and Edmund of Langley, sons of Edward III, there are two opportunities, as one son could have been by Edward III, and one not.) In terms of how any of this could have affected royal succession during the Wars of the Roses with either the House of Lancaster or House of York making claims to the throne, only five of these instances are germane: those generations between the sons of Edward III and Richard III –and (to a degree) Henry VII.

It is important to keep in mind that, as much as claims to the English throne relied on inheritance through the male or female lines of the “Plantagenet” royal family, for much of this period the throne was claimed by right of conquest: possession meant far more than blood. Still, considering the genealogical implications of this new discovery for the English royal family of the medieval period, there are not a whole lot of other avenues for finding male line descendants to compare with Richard III.

The Somerset family are the only surviving male line descendants of King Edward III. As my genealogical research indicates, there may only be only one other generation between the 5th Duke of Beaufort and John of Gaunt for other male line descendants to be found, and that is with Henry Somerset, 1st Marquess of Worcester (1577–1646), who had nine sons, some of whom may have left surviving male-line descendants. This Henry is nine generations after John of Gaunt and seven generations before the 5th Duke of Beaufort. Other than this one other possibility, there are no other surviving male-line descendants of Edward III to be tested (and I’m not absolutely sure other male-line descendants of this Lord Worcester exist). Say descendants through a younger son of the 1st Marquess of Worcester can be found and tested, the options are:

1) They could have the same Y-DNA as Richard III (thus the break occurred between the 1st Marquess of Worcester and his descendant, the 5th Duke of Beaufort, and nothing regarding the lineage of the York and Lancaster kings is affected);

2) They could have the same Y-DNA as the descendants of the 5th Duke of Beaufort (thus the break occurred between Lord Worcester and Richard III, at any of the thirteen opportunities indicated above, with only five instances potentially affecting the claims of the York and Lancaster kings); or

3) They could have a completely different Y-DNA, thus introducing at least one other false-paternity event at some other undetermined point.

Going further back in the patrilineal ancestry of Edward III, another option possibly exists in testing the Y-DNA of the Cornewalls. These are the male line descendants of the younger brother of King Henry III (1207–1272), the great-grandfather of Edward III. The younger brother, Richard, Earl of Cornwall and “King of the Romans” (1209–1272), had surviving patrilineal descendants living in the early twentieth century through his two illegitimate sons, Richard and Walter de Cornwall. These descendants were published in the 1908 genealogy The House of Cornewall by the 4th Earl of Liverpool and Compton Reade. Say male-line descendants alive today of Richard, Earl of Cornwall, are found and tested, there are possible outcomes:

1) They could have the same Y-DNA[1] as Richard III[2];

2) They could have the same Y-DNA as the descendants of the 5th Duke of Beaufort[3]; or

3) They could have a completely different Y-DNA, thus introducing at least one other false-paternity occurring at some other undetermined point.

The other remaining option, which seems unlikely, would involve the exhumation of some king closely related in the male line to King Richard III. The kings that are candidates for this would be: Henry II, Richard I, John, Henry III, Edward I, Edward II, Edward III, Richard II, Henry IV, Henry V, Henry VI, and Edward IV.[4]

In conclusion, I think it’s incorrect to say these DNA results seriously affect the claims of the House of York, Lancaster, Tudor or the current royal family. (Remember, the current rights of succession have to do with descent from Sophia, Electress of Hanover [1630–1714], and would not be affected by her ancestry.) While the patrilineal ancestry of six kings during this period may be in question, the overwhelming majority of potential false-paternity events would have occurred after 1500, and so can have nothing to do with Richard III’s ancestry – and, in fact, putting the question in those terms reveals how speculative the whole subject remains.

Notes

[1] It should be pointed out the claim of the House of York related to their descent, through females, from Lionel of Antwerp, Duke of Clarence (the second son of Edward III). Their patrilineal descent from Edmund of Langley, Duke of York, herein discussed, is relevant with regard to their male-line ancestry, but not so much with their claim to the throne.

[2] The break occurred between Edward III [only through his son John of Gaunt, Duke of Lancaster, ancestor of the Worcesters and Beauforts] and the 5th Duke of Beaufort, at any of the fifteen opportunities, with only one of these fifteen opportunities affecting the claims of the House of Lancaster (and two regarding the ancestry of Henry VII), and none affecting the lineage of the House of York.

[3] The break occurred between Edward III [only through his son Edmund of Langley] and Richard III, thus allowing for only four opportunities of a false paternity event, all affecting the lineage of the House of York (the last one only affecting Richard III if Edward IV and Richard III had different fathers), and confirming the ancestry of the Houses of Lancaster and Tudor (through Henry VII’s mother Lady Margaret Beaufort, the heiress of John of Gaunt).

[4] The remains of the uncrowned Edward V and his brother Richard, Duke of York, would also be useful, if their location is ever found.

Share this:

About Christopher C. Child

Chris Child has worked for various departments at American Ancestors since 1997 and became a full-time employee in July 2003. He has been a member of American Ancestors since the age of eleven. He has written several articles in American Ancestors, The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, and The Mayflower Descendant. He is the co-editor of The Ancestry of Catherine Middleton (American Ancestors, 2011), co-author of The Descendants of Judge John Lowell of Newburyport, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2011) and Ancestors and Descendants of George Rufus and Alice Nelson Pratt (Newbury Street Press, 2013), and author of The Nelson Family of Rowley, Massachusetts (Newbury Street Press, 2014). Chris holds a B.A. in history from Drew University in Madison, New Jersey. Areas of expertise: Southern New England, especially Connecticut; New York; ancestry of notable figures, especially presidents; genetics and genealogy; African-American and Native-American genealogy, 19th and 20th Century research, westward migrations out of New England, and applying to hereditary societies. Chris has lectured on these topics and edits the genetics and genealogy column for American Ancestors.View all posts by Christopher C. Child →