As part of his schoolwork, my nephew is working on a family tree showing his forebears. The assignment seems fairly flexible: Show as many ancestors as you can, or, if you don’t have much information, focus in greater depth on the more recent ones you do know.

My brother-in-law is just getting started on his genealogy, so I suggested beginning with what he knew: the identities of his parents and grandparents. I pointed Christopher toward the California Birth Index, 1905-1995, as he should be listed there, and toward Lindsay Fulton’s Vita Brevis post on Social Security Administration applications, since information on his twentieth-century ancestors will be found in those files. When he’s finished there, Christopher can start working back through the various Federal Censuses available on Ancestry.com. He tells me he has a family tree of his father’s family, created by a great-aunt, and this will be helpful as he becomes familiar with the various vital and civil registration databases to be found at FamilySearch.org, Ancestry.com, and elsewhere.

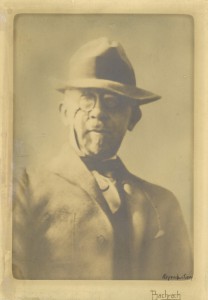

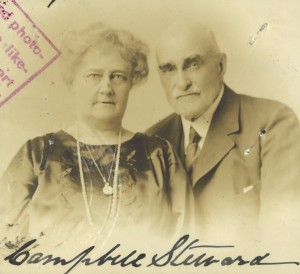

For my sister and me, we have an embarrassment of riches: genealogies have been written about the families of three of our four grandparents. My 2003 book on the Le Roys (written with Newbold Le Roy, 3rd) brings the Steward, White, Le Roy, Rutgers, and van den Berg families in our line down to Meg’s marriage in 2002. My Ayer genealogy (published in 1993) covers the Ayer, Ilsley, Wheaton, Cook, Fanning, Deake, Colt, Travis, and Hutchins families back into the seventeenth century. Finally, a 1925 Glidden genealogy follows the Glidden line down to the birth of my maternal grandmother in 1903, and a more recent one covers my mother and her descendants.

I can, and will, give my nephew the information on Meg’s (and my) recent ancestry, but the project also makes me think about how I would begin again, if I had to start over. As I say, there are many genealogies available on the various parts of my family; it gives me pause to think how long it took me to find the ones available when I started this process the first time, as well as their strengths and weaknesses, but on balance I’ve been incredibly lucky in the work many other genealogists have done and are doing on questions having to do with my ancestry.

Then there are the masses of published vital records, and, since the 1990s, the incalculable array of databases now available online. Writing that 2003 genealogy was made much easier with access to The New York Times and, with more recent books, the Massachusetts Vital Records, 1841-1915, databases available at AmericanAncestors.org.

The lists goes on – I’m so thankful for Findagrave.com and Fold3.com – but what ties all these different record types together is the habit of mind, developed in the stacks at NEHGS and the New York Genealogical & Biographical Society, of checking one source against another, going from book to microfiche to commercial database to book to manuscript to manuscript to published vital record to…

Well, you get the picture!

Share this:

About Scott C. Steward

Scott C. Steward has been NEHGS’ Editor-in-Chief since 2013. He is the author, co-author, or editor of genealogies of the Ayer, Le Roy, Lowell, Saltonstall, Thorndike, and Winthrop families. His articles have appeared in The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, NEXUS, New England Ancestors, American Ancestors, and The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, and he has written book reviews for the Register, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, and the National Genealogical Society Quarterly.View all posts by Scott C. Steward →