I used to joke that I rarely thought about politics more than twenty-four hours a day. In fact, my pursuit of genealogical research developed alongside my work in opposition and campaign research. Exposed to a variety of Washington, D.C. area archives and repositories, I quickly gathered many records relating to my ancestors from primary sources kept in the same places I consulted in the course of my campaign efforts. Last week, as I researched the nineteenth-century ancestors of our Research Services clients amidst the news of electoral victories and disappointed prospects, I found myself thinking of an interesting source of records that genealogists rarely consult.

I used to joke that I rarely thought about politics more than twenty-four hours a day. In fact, my pursuit of genealogical research developed alongside my work in opposition and campaign research. Exposed to a variety of Washington, D.C. area archives and repositories, I quickly gathered many records relating to my ancestors from primary sources kept in the same places I consulted in the course of my campaign efforts. Last week, as I researched the nineteenth-century ancestors of our Research Services clients amidst the news of electoral victories and disappointed prospects, I found myself thinking of an interesting source of records that genealogists rarely consult.

If I asked you, Would your ancestor have voted for Lincoln or Douglas, would you know the answer? Historic voter rolls can put flesh on the bones of our ancestors, providing biographical information which gives insight into who they were and what their concerns might have been. We may correlate party affiliation with the partisan concerns of the same period, gleaned from published party platforms (or, less reliably, by checking out Wikipedia’s digest of each major election and presidential administration). In so doing, we gain a sense of who our forebears were and what some of their chief concerns may have been.

If I asked you, Would your ancestor have voted for Lincoln or Douglas, would you know the answer? Historic voter rolls can put flesh on the bones of our ancestors, providing biographical information which gives insight into who they were and what their concerns might have been. We may correlate party affiliation with the partisan concerns of the same period, gleaned from published party platforms (or, less reliably, by checking out Wikipedia’s digest of each major election and presidential administration). In so doing, we gain a sense of who our forebears were and what some of their chief concerns may have been.

Especially when party enrollment changed over several years, we can intuit that an issue or a political figure inspired the move. In rare cases where personal records of ancestors survive, such as correspondence or videos in our own households or a manuscript in the R. Stanton Avery Special Collections at NEHGS, we can find that our ancestors mentioned events and ideas we can tie to a party shift in the voter rolls. In this way, we can support our characterization of our ancestors’ beliefs and behavior with evidence from primary sources. While we might today imagine that our parents or grandparents were avid supporters of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, records showing resolute Republican affiliation should cause us to reconsider our present perspective.

Especially when party enrollment changed over several years, we can intuit that an issue or a political figure inspired the move. In rare cases where personal records of ancestors survive, such as correspondence or videos in our own households or a manuscript in the R. Stanton Avery Special Collections at NEHGS, we can find that our ancestors mentioned events and ideas we can tie to a party shift in the voter rolls. In this way, we can support our characterization of our ancestors’ beliefs and behavior with evidence from primary sources. While we might today imagine that our parents or grandparents were avid supporters of Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal, records showing resolute Republican affiliation should cause us to reconsider our present perspective.

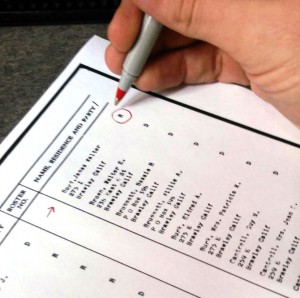

Will we be surprised to find our ancestors were Republicans when we were raised in a Democratic household? Where can we look for the records that would answer such questions? As it happens, Ancestry and other commercial sites have recently digitized some collections of historic voter registration records (enter “voter” or “electoral” in the keyword section of the card catalog search). Also, some state archives have begun digitization projects, such as Alabama’s digitized 1867 historic voter rolls. Voter registration records are publicly accessible in most U. S. states. Generally, an e-mail to your state’s Office of the Secretary of State requesting information about access will be answered with the hours one can search the records and their protocol for doing so. Local registries are also public records, but access can sometimes be complicated by local officials’ broad application of privacy directives and because these officials often retain the right to restrict use of the collection. However, with patience and the polite assertion that you seek access for a bona fide research purpose, you may be able to trace your family’s political leanings for generations.

Will we be surprised to find our ancestors were Republicans when we were raised in a Democratic household? Where can we look for the records that would answer such questions? As it happens, Ancestry and other commercial sites have recently digitized some collections of historic voter registration records (enter “voter” or “electoral” in the keyword section of the card catalog search). Also, some state archives have begun digitization projects, such as Alabama’s digitized 1867 historic voter rolls. Voter registration records are publicly accessible in most U. S. states. Generally, an e-mail to your state’s Office of the Secretary of State requesting information about access will be answered with the hours one can search the records and their protocol for doing so. Local registries are also public records, but access can sometimes be complicated by local officials’ broad application of privacy directives and because these officials often retain the right to restrict use of the collection. However, with patience and the polite assertion that you seek access for a bona fide research purpose, you may be able to trace your family’s political leanings for generations.

Share this:

About Christopher Carter Lee

Christopher Carter Lee completed undergraduate studies in international relations at Georgetown University in Washington, D.C., where he focused on culture and politics. He previously worked in foreign policy research, special projects and development for a U.S. Senate office, and as a political consultant, appearing on CNN's Crossfire. More recently, he built his own hired genealogical research practice while consulting in program development before joining NEHGS Research Services. He holds a Certificate in Genealogical Research from Boston University and has extensive knowledge of Maryland, Virginia, Southern U.S., and Southeastern American Indian genealogy, the Catholic Church in North America, and expertise in Italian, French, Polish, Russian, and other European research, nobility, heraldry, and history.View all posts by Christopher Carter Lee →