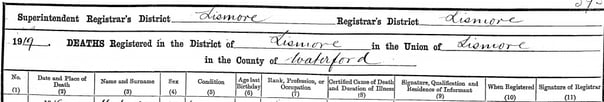

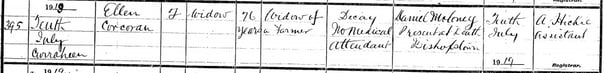

Cause of death: senile gangrene, commonly known today as arteriosclerosis, or the thickening and loss of elasticity in the arteries.

Cause of death: senile gangrene, commonly known today as arteriosclerosis, or the thickening and loss of elasticity in the arteries.

No document is more pivotal to genealogical work than a death certificate. The reason for its importance goes far beyond simply providing researchers with a date of death for an individual. Perhaps just as critical to understanding family history as the date of death is the cause of death.

Records of deaths were originally kept by churches in the colonial period, but eventually these records led to the development of legal documents which served a similar purpose. The Massachusetts Bay Colony made courts responsible for death records in 1639, going against the traditional European model of having churches record deaths as well as baptisms and marriages.

Despite this, no universally accepted death certificate model was put into place throughout America until 1910.[1] Because of this, doctors and other officials lacked widely-accepted terminology for various causes of death and, as a result, many antiquated and long-abandoned terms for illnesses were printed on these documents well into the twentieth century.

Knowing the meaning and origins of these outmoded terms can provide researchers with a cause of death for an individual, in turn revealing a great deal about both the life and death of the deceased. For instance, knowing that Bronze John is an archaic term for yellow fever or that ‘Bladder in Throat’ referred to diphtheria[2] allows researchers to infer that the individual in question likely suffered a long-drawn-out death affecting other family members physically, emotionally, and financially. Furthermore, knowing that a death was likely expected at the time, one can surmise that the deceased composed a last will and testament or made the appropriate amendments to an existing will.

Conversely, other long-discarded terms such as Dry Bellyache, meaning lead poisoning, or ‘Softening of the brain’[3], a result of stroke or hemorrhage of the brain, indicate an unexpected and quick death, which likely would have a long-lasting effect on the deceased’s family, forcing children to work to make up for lost wages or a relocation to find employment. Additionally, financial hardship as a result of an unexpected death might require the spouse of the deceased individual to move in with other family members, in turn necessitating household shifts, whether in the same town or across several states.

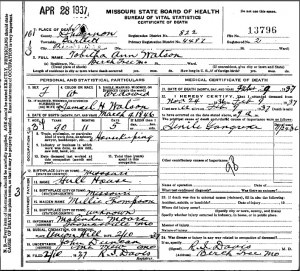

The cause of death can tell researchers about how a person lived - as well as how they died. Michael N. Regent of Chicago died in 1908 after consuming a tainted caviar sandwich.

The cause of death can tell researchers about how a person lived - as well as how they died. Michael N. Regent of Chicago died in 1908 after consuming a tainted caviar sandwich.

Causes of death also tend to reveal quite a bit about historical changes over time. According to data provided by the Center for Disease Control, ailments which were among the top causes of death in America in 1900, such as influenza and tuberculosis, were not among the top ten in 2010.[4] While these illnesses are no longer considered a major threat, they were a very real concern for men and women across the world a century ago. An ailment such as pneumonia may look out of place as a cause of death to modern readers, but only three generations ago it was the most commonly listed cause of death on death certificates.

Knowing and understanding the cause of death of an ancestor can also help genealogists with another critical tool: gravestones. Gravestones often provide, at the very least, a year of birth and a year of death, as well as a burial place for an individual. Knowledge of an individual’s cause of death may significantly affect the search for a gravestone. I am a descendant of Captain John Luther, one of the founders of the town of Swanzey (now known as Swansea), Massachusetts. He was killed by Native Americans during a trading expedition in the Delaware Bay, and because of the nature of his death, Luther was ultimately buried at sea and so had no gravestone in Swansea, eliminating the possibility of finding this resource to advance my research. Knowing the cause of an ancestor’s death can completely change the way that genealogists approach a research problem, and for this reason, this information is critical to uncovering family history.

Notes

[1] http://www.nytimes.com/2013/07/02/health/making-the-right-call-even-in-death.html?_r=0.

[2] US GenNet, “Old Disease Names Frequently found on Death Certificates” http://www.usgennet.org/usa/ar/county/greene/olddiseases1.htm.

[3] US GenNet, “Old Disease Names Frequently found on Death Certificates” http://www.usgennet.org/usa/ar/county/greene/olddiseases1.htm.

[4] Gwen Sharp, PhD, “Historical Changes In Causes Of Death” Sociological Images, 25 June 2012, http://thesocietypages.org/socimages/files/2012/06/causeofdeath.png.

Share this:

About Zachary Garceau

Zachary J. Garceau is a former researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. He joined the research staff after receiving a Master's degree in Historical Studies with a concentration in Public History from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and a B.A. in history from the University of Rhode Island. He was a member of the Research Services team from 2014 to 2018, and now works as a technical writer. Zachary also works as a freelance writer, specializing in Rhode Island history, sports history, and French Canadian genealogy.View all posts by Zachary Garceau →