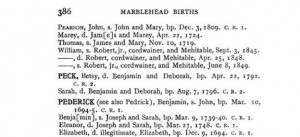

I was recently asked a question about how surnames were assigned to illegitimate children born in the seventeenth century: Was the surname of the father, or the mother, given to the child? Since illegitimate births were uncommon in New England during the 1600s (about 92% of first children born through 1680 were delivered nine months or more after their parents’ marriage), the illegitimate child could have been given the surname of the mother OR the father, depending on the circumstances. Typically, the illegitimate child would assume the surname of the mother when the identity of the father was unknown. For example, Elizabeth Pederick was the illegitimate daughter of Elizabeth Pederick, baptized in Marblehead 9 December 1694. No father was listed.

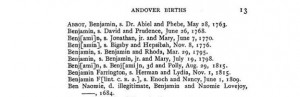

However, if the identities of both parents were known, the child’s birth record would be filed under the surname of the father, while still indicating the name of the father and the mother. For example, Ben Naomie Abbot was the illegitimate daughter of Benjamin Abbot and Naomie Lovejoy, born in 1684 in Andover, Massachusetts.

However, if the identities of both parents were known, the child’s birth record would be filed under the surname of the father, while still indicating the name of the father and the mother. For example, Ben Naomie Abbot was the illegitimate daughter of Benjamin Abbot and Naomie Lovejoy, born in 1684 in Andover, Massachusetts.

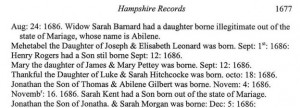

In other circumstances, the illegitimate child could have been given the surname of the mother, then, later, the surname of the father (or step-father). For example, Abilene Barnard, the illegitimate daughter of the widow Sarah Barnard, was born on 24 August 1686. The record specifically states that Abilene was born out of the state of marriage.

In other circumstances, the illegitimate child could have been given the surname of the mother, then, later, the surname of the father (or step-father). For example, Abilene Barnard, the illegitimate daughter of the widow Sarah Barnard, was born on 24 August 1686. The record specifically states that Abilene was born out of the state of marriage.

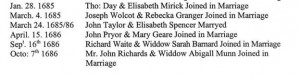

Twenty-three days later, on 16 September 1686, Sarah Barnard married Richard Waite. This may point to evidence that the illegitimate child, Abilene Barnard, was the biological daughter of Richard Waite.

Twenty-three days later, on 16 September 1686, Sarah Barnard married Richard Waite. This may point to evidence that the illegitimate child, Abilene Barnard, was the biological daughter of Richard Waite.

Later, on 14 March 1689/90, Abilene Waite, the daughter of Richard Waite, died.

Later, on 14 March 1689/90, Abilene Waite, the daughter of Richard Waite, died.

While one cannot know based on these records whether Abilene Barnard/Waite was the biological daughter of Richard Waite or his step-daughter, the records do prove that illegitimate children could adopt a surname over time. To prove a more definitive connection between an illegitimate child and a (proposed) father, researchers should expand their research to include records such as probate records, pension files, or church records.

Share this:

About Lindsay Fulton

Lindsay Fulton joined the Society in 2012, first a member of the Research Services team, and then a Genealogist in the Library. She has been the Director of Research Services since 2016. In addition to helping constituents with their research, Lindsay has also authored a Portable Genealogists on the topics of Applying to Lineage Societies, the United States Federal Census, 1790-1840 and the United States Federal Census, 1850-1940. She is a frequent contributor to the NEHGS blog, Vita-Brevis, and has appeared as a guest on the Extreme Genes radio program. Before, NEHGS, Lindsay worked at the National Archives and Records Administration in Waltham, Massachusetts, where she designed and implemented an original curriculum program exploring the Chinese Exclusion Era for elementary school students. She holds a B.A. from Merrimack College and M.A. from the University of Massachusetts-Boston.View all posts by Lindsay Fulton →