Patrilineage

One of my sisters recently asked me if we might be related to a friend of hers named Boucher, and I explained that we almost certainly were not, as the surname died out with our great-great-aunt Florence Estella Boucher (1879–1972). Our great-great-grandfather Boucher had eleven sons, only three of whom married. The youngest, Emile Gabriel Boucher (1886–1950), had no children, while the son of Louis Albert Boucher (1871–1914?) changed his first name and adopted his stepfather’s surname; only Francis Xavier Boucher (1854–1927) had Boucher sons, Milton and Edward, and only Milton married. I am unaware of any descendants of either brother.

It’s curious to think of this large family – twenty-three children, twenty-five grandchildren, and fifty great-grandchildren – leaving no males with the surname, although I suppose it often happens. There are, of course, about one hundred Boucher descendants in those three generations, bearing many surnames – and often carrying Boucher as a middle name – but for whatever reason the male line failed within seventy years of William Boucher Jr.’s death in 1899.

Matrilineage

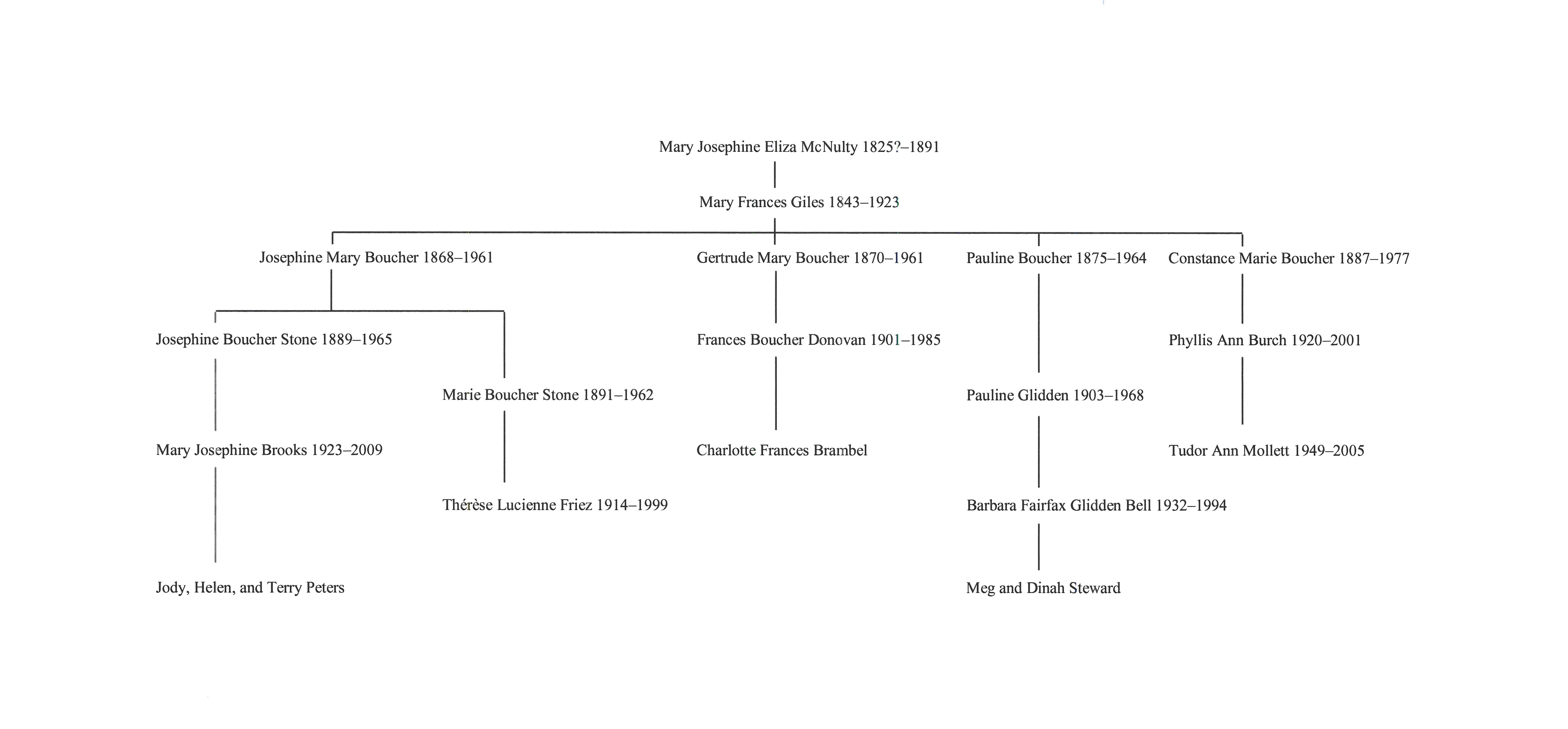

Just as surprising is the female line, which happens to be my matrilineal line. I can trace this line back to my great-great-great-grandmother, Mary Josephine Eliza McNulty (1825?–1891), whose only child married William Boucher Jr. in 1865. The Bouchers had eight daughters, six of whom married; four of the married daughters had daughters, as shown in the accompanying chart. (Click to enlarge)

But while Frances Giles Boucher had four daughters who left female offspring, she had only five granddaughters and five great-granddaughters with daughters of their own: a grand total of five great-great-granddaughters, including my two sisters and three of our third cousins. Of course, what the chart does not show is that there are other living descendants of Eliza McNulty in the female line: the brothers and children of the Peters sisters, Thérèse Friez’s son, my brother and I, my nephew, and Tudor Mollett’s brothers and Plummer first cousins. Still, at this stage there are only a handful of us, in comparison to the more than 150 descendants of William Boucher Jr. by his two wives.

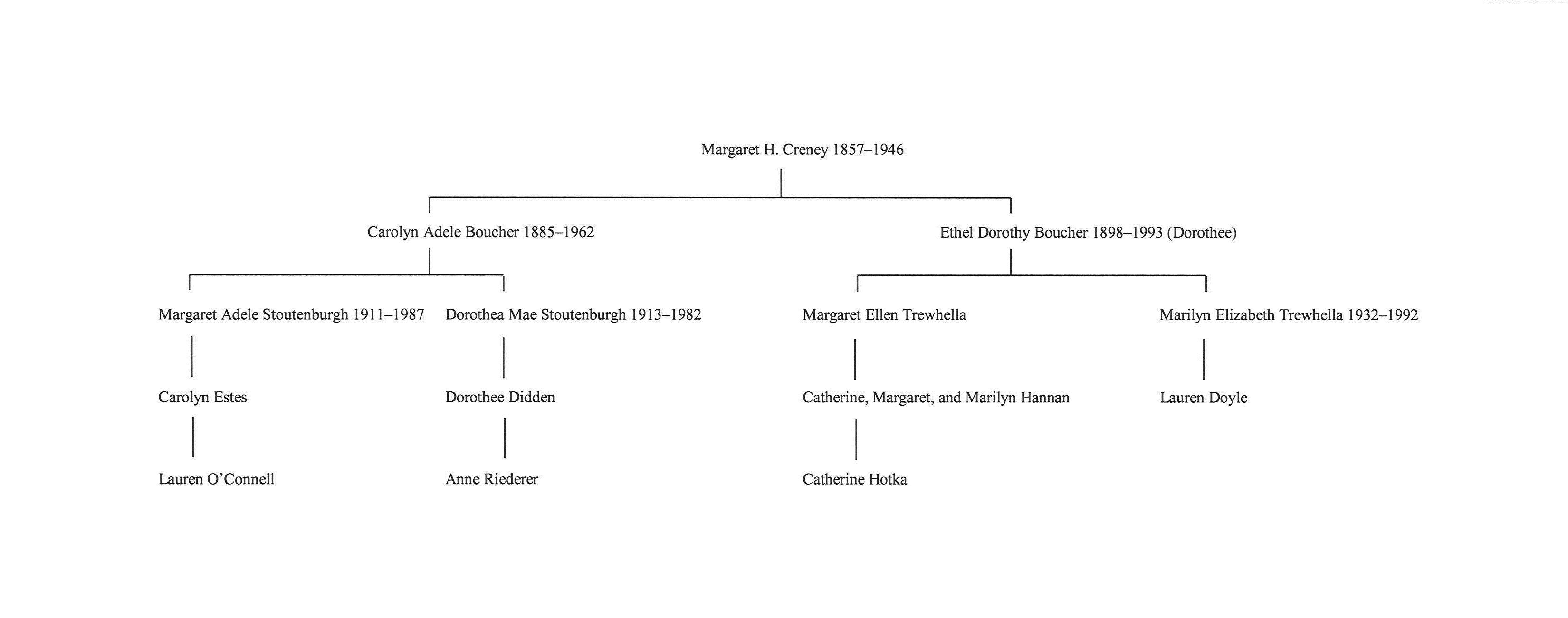

It is interesting to note that the matrilineage of Margaret H. (Creney) Boucher (1857–1946), who married Frank Boucher in 1875, is on about the same scale: she had three daughters, four granddaughters, six great-granddaughters, and at least three great-great-granddaughters (and their brothers). This, among a grand total of five children, seven grandchildren, about fifteen great-grandchildren, and about twenty-eight great-great-grandchildren: a much smaller pool of progeny, with a somewhat higher percentage of descendants through female lines.

It is interesting to note that the matrilineage of Margaret H. (Creney) Boucher (1857–1946), who married Frank Boucher in 1875, is on about the same scale: she had three daughters, four granddaughters, six great-granddaughters, and at least three great-great-granddaughters (and their brothers). This, among a grand total of five children, seven grandchildren, about fifteen great-grandchildren, and about twenty-eight great-great-grandchildren: a much smaller pool of progeny, with a somewhat higher percentage of descendants through female lines.

We tend to focus on surnames, as they give us a sense of identity. I find it interesting to think about the women – and their families – in my ancestry and among my cousinship, especially since the geographic dispersal (and, until recently, the erasure of surname identity) for women can be so great. With the Boucher reunion in the offing, I hope that many of my cousins, through the male and the female line alike, will rediscover their kinship in Baltimore.

The series continues here.

Share this:

About Scott C. Steward

Scott C. Steward has been NEHGS’ Editor-in-Chief since 2013. He is the author, co-author, or editor of genealogies of the Ayer, Le Roy, Lowell, Saltonstall, Thorndike, and Winthrop families. His articles have appeared in The New England Historical and Genealogical Register, NEXUS, New England Ancestors, American Ancestors, and The Pennsylvania Genealogical Magazine, and he has written book reviews for the Register, The New York Genealogical and Biographical Record, and the National Genealogical Society Quarterly.View all posts by Scott C. Steward →