During this festive time of the year, magical Christmas “villages” seem to pop up everywhere, transforming nooks in the home as well as entire downtowns. It is a loaded word and whenever I see “village” attached to a place (and not only during the Christmas season), be it a village inn, pub, green, or a village itself, I am immediately enchanted. The word conjures up all the nostalgia of yesteryear with the hope and anticipation of reclaiming a bit of quaintness, simplicity, and charm. I live in an area of many of the country’s oldest towns and, because they were “unplanned” towns that grew organically, often in a haphazard way, even the busiest of these places retain pockets of their “village” atmosphere, complete with narrow streets, clustered old buildings, bricks and cobbles, town clocks, and Dickensian lampposts.

During this festive time of the year, magical Christmas “villages” seem to pop up everywhere, transforming nooks in the home as well as entire downtowns. It is a loaded word and whenever I see “village” attached to a place (and not only during the Christmas season), be it a village inn, pub, green, or a village itself, I am immediately enchanted. The word conjures up all the nostalgia of yesteryear with the hope and anticipation of reclaiming a bit of quaintness, simplicity, and charm. I live in an area of many of the country’s oldest towns and, because they were “unplanned” towns that grew organically, often in a haphazard way, even the busiest of these places retain pockets of their “village” atmosphere, complete with narrow streets, clustered old buildings, bricks and cobbles, town clocks, and Dickensian lampposts.

Just the other day, driving through Dorchester, an urban neighborhood of Boston, I passed through a place called Adams Village and, indeed, it had something of that charm for which I’m always searching. It seems that the “village” is something that many places, with the hustle, bustle, and sameness of modern life (and far too many vehicles), make a deliberate effort to promote, particularly during the Christmas season. The downtown merchants here in my town are always talking about how hard they strive, year-round, to maintain the “village atmosphere,” though with 25,000 of us inhabiting this place I suspect the “village” represents more of an ideal than reality. But in the town next to mine, there is a quaint old neighborhood called Hull Village. Perhaps because I don’t live there and am not jaded by seeing it every day, it really does live up to expectations and has the “feel” of yesteryear.

First settled in 1622 as Nantascot and incorporated in 1644, when it was officially named for the English port town of Kings-town-upon-Hull, the Massachusetts namesake, a long, narrow peninsula forming the southern rim of Boston Harbor, became a trading post for Plymouth Colony and, later, during the Revolutionary War, a strategic outpost.[1] Hull’s vulnerability to the sea made it another kind of strategic outpost when the Massachusetts Humane Society, founded in 1786, located one of its first protective shelters for shipwrecked and stranded sailors on Nantasket Beach. In time, as the Humane Society evolved into the United States Lifesaving Service (1871) – later the United States Coast Guard (1915) – the selfless and heroic rescues by Hull’s volunteer lifesaving crews became legendary.

No lifesaver was more celebrated than Hull-born Joshua James (1826-1902), the ninth of twelve children born to a Dutch sea captain father, William James, and a mother, Esther Dill, whose family was rooted deep in New England. Growing up in Hull Village at the edge of the snug cove with its fleet of schooners, Joshua had gone to sea from a young age with his father and older brothers. By the early 1840s, when lifesaving efforts were first organized, Joshua volunteered to man the lifeboats of the Humane Society. Tragically, five years earlier he had witnessed the drowning of his mother and baby sister when the paving-stone vessel on which they were passengers from Boston – a vessel owned by Joshua’s older brother – foundered in Hull Gut, trapping them in the cabin. As one account noted, had their life not been lost in this tragic manner, “Joshua might never have been led to consecrate his life to the rescue of others in a similar fate.”

The distinguished and decorated lifesaving career of Captain Joshua James, spanning sixty years – including heroic efforts during the 1898 Portland storm – and hundreds of lives saved, came to a dramatic and unexpected end. Though past the mandatory retirement age for federal appointments, in 1889 Joshua had been given a special waiver and was appointed keeper of the new station at Point Allerton (now a museum), Allerton Hill having been named for Mayflower passenger Isaac Allerton. Always diligent in drilling and training his crews, on 19 March 1902, he summoned his crew for extra training in the aftermath of a tragedy two days earlier that had claimed the lives of crewmembers at the Monomoy Point Station on Cape Cod. Captain James, then seventy-five years old, drilled his crew for an hour in rough surf, returned to the beach and fell dead from heart failure.

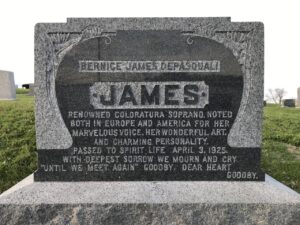

He was buried in the ancient Hull Village Cemetery, on the gently sloping Gallop’s Hill, his resting place marked with a prominent and elaborately inscribed stone. Fittingly, in 1990 the Hull Historical Society placed a marker (above), inscribed Strangers Corner, recognizing the unidentified victims – known only to God – of shipwrecks that Joshua James and his crew had risked their own lives attempting to save. Many members of the extended James family also rest in the cemetery, including Joshua’s brother, Captain Reinier James (1816-1902), owner of the sloop on which their mother and sister had perished. Some family histories relate the tragic coincidence of Reinier, as a young boy, having been rescued by his mother from drowning in a well.

Reinier was the father of Captain William Wallace James (1836-1920), who married Eliza Anna Lucihe (1850-1939), the daughter of John Lucihe (1803-1878), a native of Ragusa [then part of the Habsburg empire], and Eliza Torrey Lovell (1818-1897), the daughter of Caleb Lovell and Jane Dill. Eliza Ann Lucihe’s sister, Louisa Francesca Lucihe, was married to Captain Joshua James.

Three children were born to William Wallace James and Eliza, the youngest of whom was Bernice, born in 1873. One tries to imagine her early life in the tiny seaside village, surrounded by the fisherfolk and her extended family. In 1880, Hull was a village of 383 residents, a place insular, sustained almost entirely by fishing, but rapidly coming to feature resort hotels, summer cottages and villas, and a growing immigrant population. By 1890 the population had swelled to 1,000 and by 1900 it had grown to 1,700. The outside world, and all it had to offer, was beginning to intrude and entice. As a young girl, Bernice’s passion was music and, shortly after the National Conservatory of Music opened in New York in the mid-1880s, Bernice enrolled as a student. By 1900, her older brother Vincent, who had gone to New York as a young man, and her parents were all living in New York, and it seems likely that the family had relocated in part for Bernice’s musical education, though without an 1890 census one can’t confirm the details.

In 1896, Bernice married a fellow Conservatory student, Salvatore de Pasquali, an Italian tenor who formed his own opera troupe with Bernice; she made her debut in 1900 as the principal soprano. Her performances were the talk of the hour in London, Berlin, St. Petersburg, and Paris, and in Italy, where she spent two years singing in Milan and Rome. On 2 January 1909, the “bird-voiced singer” made her New York debut at the Metropolitan Opera, electrifying the audience with her debut as Violetta in La Traviata. She remained at the Met for six years as principal coloratura, singing fifty-six performances. It was said that few sopranos of the day could rival Bernice’s fifty-four-opera repertoire.

If you could take the girl out of Hull, there was no taking Hull out of the girl. Though she had become an international star who had sung with Caruso and been conducted by Mahler, Bernice James de Pasquali remained a small-town girl to the end. When she wasn’t performing at Christmastime, she came home to Hull Village to share the holiday, gathering family and friends in Elm Square, in front of the library – a shingle-style private home until 1913, when it was purchased by the town – to sing Silent Night on Christmas Eve.

If you could take the girl out of Hull, there was no taking Hull out of the girl. Though she had become an international star who had sung with Caruso and been conducted by Mahler, Bernice James de Pasquali remained a small-town girl to the end. When she wasn’t performing at Christmastime, she came home to Hull Village to share the holiday, gathering family and friends in Elm Square, in front of the library – a shingle-style private home until 1913, when it was purchased by the town – to sing Silent Night on Christmas Eve.

It was in another village, in Austria, in 1818 that Silent Night – Stille Nacht in the original German – was first heard during a Christmas Eve mass. In the devastating aftermath of the Napoleonic Wars, a young Catholic priest, Father Joseph Mohr, had written a six-verse poem as a message of hope for his traumatized congregation. Franz Xaver Gruber, a local schoolteacher and organist, composed the lilting melody for the comforting lyrics. Traveling folk singers began including the carol in their repertoire and in 1839 the Rainer family brought the song to America, where it was heard for the first time at Trinity Church (of Alexander Hamilton fame) in lower Manhattan. In time, the powerful message of peace and reconciliation was translated into virtually every language.

One imagines that message, on Christmas Eve in the seaside village, carried on Bernice’s crystalline soprano voice, floating over the gathering night – perhaps a starlit night with a sliver of moon above the bay – a timeless message to soothe the souls of family, friends, and strangers, the living and the departed. All was calm. All was bright.

Merry Christmas!

Note

[1] For an interesting treatment of Hull’s name origins, see Albert Matthews, “The Naming of Hull, Massachusetts,” The New England Historical and Genealogical Register 59 [1905]: 177-86.

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →