As a Scottish woman feeling the impact of Brexit, I, like many others in the United Kingdom, have started the process of claiming Irish citizenship. I am a summer intern with the development team at NEHGS, where I have gained some insights about how the institution works, but until recently I hadn’t learnt anything about my own ancestry. With my internship drawing to a close, I arranged a meeting with Sheilagh Doerfler in Research Services to discuss my paternal ancestry.

Whilst I’ve had success researching my mother’s side of the family, I am estranged from my father, and so cannot ask him anything about his lineage. This is inconvenient, as his mother is the key to my Irish passport.

I always knew that I had an Irish grandparent, but nothing else about her. “I’m part Irish,” I’d proudly exclaim, without any evidence. It was only before the meeting that I asked my Mum which grandparent was in fact, from Northern Ireland. “Agnes,” she said. “But she died long before I met your Dad.”

As we discussed my aims in our zoom call, Sheilagh introduced me to a range of websites and resources: Scotland’s People, irishgenealogy.ie, and townlands.ie. We went through them together and worked with what I knew to find my grandmother’s birth, death, and marriage certificates. Agnes (McGeown) Aimers was born in Northern Ireland and died in Edinburgh, decades before I was born. This information is enough to claim citizenship, and I was over the moon, but we continued further.

For three generations, my family lived, got married, worked, and died within the same area.

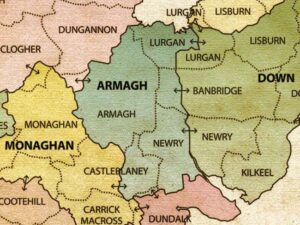

What soon emerged was a picture of my paternal grandmother’s side rooted in Armagh, Ireland. For three generations, my family lived, got married, worked, and died within the same area. The McGeown name, I would learn, was very rare in Ireland – localised to Armagh and the surrounding area. It comes from Eoghan, which isn’t surprising. I saw my great-great-great-grandfather’s land, and the buildings which still exist on it, thanks to Griffith’s Valuation. I’ve been able to use Google Maps to walk down the roads my ancestors did – and maybe my distant relatives still do!

The most interesting discovery of the day, however, was regarding Agnes (Bell) McGeown, my great-grandmother. Her marriage certificate, dated 1917, stated that her mother was (another) Agnes Bell, and her father was unknown. My eyes lit up with this. We searched for more information, but my great-grandmother’s birth was never registered. She didn’t show up in the censuses we found. The implication is an illegitimate birth, which would have been scandalous for the time (and my Catholic family).

At the end of my meeting, I realised that I’d hit my first dead end as a genealogist at same time as my biggest success – and I don’t even know where to begin. I’m juggling three generations of Agneses, with only titbits of information. I just want to know more, and especially about Agnes (Bell) McGeown, my great-grandmother, and her mother Agnes Bell, who must have suffered many hardships. There is something so exciting about uncovering their story and, now, I’ll have to be very determined to make any headway at all.

At the end of my meeting, I realised that I’d hit my first dead end as a genealogist at same time as my biggest success – and I don’t even know where to begin. I’m juggling three generations of Agneses, with only titbits of information. I just want to know more, and especially about Agnes (Bell) McGeown, my great-grandmother, and her mother Agnes Bell, who must have suffered many hardships. There is something so exciting about uncovering their story and, now, I’ll have to be very determined to make any headway at all.

Agnes Aimers and her mother are the key to my Irish passport and, thus, my key to Europe. I found out about them because I don’t speak to my father – and maybe if I did, I wouldn’t have bothered to search his side. I never grew up with a father, and neither did my great-grandmother. That makes me feel comforted, in a strange way. I don’t know about you, but that feels like a full circle to me.

Share this:

About Jade Aimers

Jade Aimers studied for her undergraduate degree in English Literature at the University of Glasgow. She joined the NEHGS team for ten weeks in the summer of 2021, on a Saltire Scotland Internship. Growing up in Edinburgh, Scotland, her research centers on Scottish and Irish genealogy.View all posts by Jade Aimers →