We are often ‘best known’ by the mementos we leave behind. After we’ve passed, an old picture book, pocket knife, glass dish, or a diary may be all that’s left to provide any clue as to who we were in life, or what may have mattered to us. As years go by, and that old picture book gets torn apart, or Cousin Johnnie misplaces the pocket knife and Niece Mary gives the glass dish away at a bake sale, well, there often isn’t much ‘left’ of anyone or even anything left to tell. While we are all so much more than just the sum total of our possessions, it can be a harder story to tell once those pieces may have lost their meaning or become scattered. It’s even more difficult when there weren’t very many to start with.

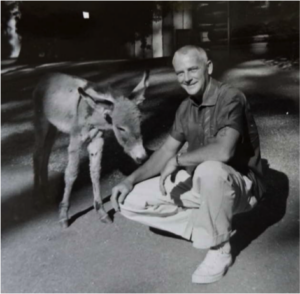

My maternal grandmother’s second husband, Clifford Reid Dixon,[1] was such a man of ‘scattered items.’ He was a great big stolid sort of guy, but regrettably someone none of us (aside from my grandmother, of course) tried very hard to get to know. The reasons for this are complicated, but suffice it to say that when Clifford passed away, all that was left of the man’s worldly possessions fit inside a ‘smallish’ cardboard box. Sadly, nobody seemed to step forward to ask who he was in life, who his family had been, or why his singular possessions all “fit so well” into that box.

Life with my grandmother, the former Mrs. Alta Lee, could not have been easy. My grandmother, an exacting sort of lady, furbished their modest apartment with items that told her story … and not too much of Clifford’s. Aside from the few trinkets Clifford had picked up through his travels in the Merchant Marine, there wasn’t much of “him” there at all. No, any visit to their quiet home would only reveal pictures of Alta’s daughter (mom) and grandkids (moi), or her sisters and parents. There were no pictures of Clifford’s kith and kin anywhere to offset Nana’s proprietary “view.”[2]

As a kid, I didn’t think much about this. I mean, it seemed only natural that any finger-painted masterpieces on Nana’s fridge should belong to me or my sisters, and that it should be my mother’s 1950s ‘glamour shot’ nicely framed in the master bedroom. I didn’t notice that something was terribly absent from the place – something, anything, indicating Clifford. Now, I don’t mean those odd trinkets Clifford had collected in Madagascar, those carved-wood and voodoo-like figures that Nana relegated to the back room. Nor do I mean those vintage 1950s adult humor joke books kept in his bathroom – a place we were gladly forbidden to enter, or even his extra ten packages of Carlton “low-tar” cigarettes in the caddy by the kitchen bar. No, we were all good there. However, when it came to any items reflective of Clifford’s family, there simply were none. Sadly, too, Clifford wasn’t the kind of guy you necessarily wanted to strike up a conversation with, or even to ask how his day went over another pack of Carltons and a refill of his bourbon glass. Looking back, I wish I’d tried a bit harder.

Looking back, I wish I’d tried a bit harder.

Clifford has been gone now for more than thirty-five years. From the vantage point of the years since then, I’ve realized that the man that my grandmother was married to (both legally and illegally) for nearly twenty-five years is someone I never knew much about.[3] Yes, I knew that he had an ex-wife, the rumored-to-be-irascible Edna, two daughters, and a grandson. One daughter, a ne’er do well hippy chick who’d literally “given up” for adoption Clifford’s only grandchild, and one who was a quiet old maid school teacher. However there were no pictures of any of them to ask about, and only the hushed whispers of grown-up conversation that accompanied all of their unknown whereabouts.

I realize, too, that Clifford never shared anything about his parents. No grainy old photograph was ever presented via some filigree patterned album, nor was there one to severely glare down from the back bedroom wall. He never waxed nostalgic, save for the memory of a favorite sports hero from last night’s game, and to his credit, he never boasted about his life in what for me then would have been those forgotten days. I did know that Clifford had a brother - a pretty swell guy named Guy (I know, go figure…) and a sister-in-law, Guy’s wife Anne. They came to visit on rare occasions and, as I recall, were pretty nice folks who just drank, smoked, and smiled a lot. They lived far away up north and seemed really old (like fifty or something…) but again, it’s not like they ever spilled the beans about the family’s past. So in light of all the not knowing anything about Clifford or his family, I decided I’d take a look. Oddly enough, Clifford’s past revealed itself almost immediately – that is to say, a branch of his mother’s family did.

*

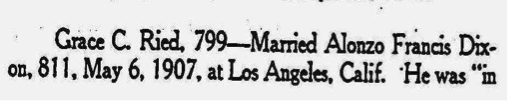

The birth of Clifford Reid Dixon is noted in California vital records, and it is mentioned in Phillip Judd and his descendants by Caroline Judd McDowell. This book is useful for tracing Clifford's ancestry through his maternal great-grandmother, Phebe Juliette (Judd) Peebles, and back to some pretty cool ancestral roots in New England. (You know me, always trying to find that lost Mayflower connection.) This book is a collection of family information “up to” the publishing date of 1923, and no doubt took many years for the author to compile. Oddly enough, it’s in this book where one of the first mysteries about the young Clifford’s life comes to light: that is, in the mention of his father, Alonzo Francis Dixon. Below is the genealogy from the Judd book for Clifford’s mother and her children:

Now, it’s important to note that the author published what she was told to be true as of “1923” and that any source of the information is only as good as the person submitting it. It’s difficult to know just who gave this information for the Judd work or when it was given. However, as I read the above genealogy, there is one thing that really caught my eye, and that was this:

“He [Alonzo Francis Dixon] was in the World War, (no record) and never came back – evidently dying in service.”

Wow! Poor Clifford! His dad went off to World War I circa 1917 and never came back! Talk about a childhood trauma! This explains so much … or does it? Remember, the author published the information she had been given, i.e., what she was told to be true at the time of compilation. Indeed, in the 1920 census for Los Angeles County, Clifford’s mother Grace (Reid) Dixon shown is listed as “widowed” and living with her four children, her “widowed” father Harry Reid (he wasn’t), and a host of other family members. Widowed or not, this was one busy household, and one trying to make ends meet. Grace Dixon even looks to have taken in a border or two to help pay the bills. One of those borders was a man by the name of Thomas Wilcox, a friend of her dad Harry’s from work. By May of 1922, Clifford’s mother Grace Dixon had married the boarder Thomas Wilcox. Amazingly enough, she appears to have never been widowed! She is now listed on the marriage application to Mr. Wilcox as “divorced.”

Wait a minute – didn’t Clifford’s dad go off to war and then was never heard from again?

Well, I guess not. By 1921, Clifford’s father Alonzo Francis Dixon was back in the Long Beach, California city directories and apparently very much returned home from the war. At first, I wondered if I wasn’t looking at the wrong “Alonzo Francis Dixon” (as you’d be surprised how many men named “Alonzo Dixon” there were in the 1920s) and, after all, the Judd genealogy said that Clifford’s dad had been lost in the Great War – but the date of birth on the World War I Draft Card for Clifford’s father Alonzo Francis Dixon, that of 29 August 1888 (and place of birth as Missouri) matched the same date and place of birth for Alonzo Francis Dixon on a World War II Draft Card for the same, and also matched the place of birth on Alonzo’s marriage license to Grace. Guess all that “lost in the war” drama was just for the published version of the family story, and not the truth. It may be part of why Clifford didn’t share anything about his mother and dad.

Clifford’s mother’s story, that of Grace C. (Reid) Dixon, while somewhat “normal” (insofar as she simply remarried the “boarder”) wasn’t really all that normal at all. I’m not sure that things worked out all that well for Grace and her new husband.[4] He was a guy who’d been married before, was a few years her senior, and probably wasn’t all that interested in taking over the duties for Grace’s teenage children. Mr. Wilcox doesn’t appear to have been in good health either, as he was admitted into a home for Disabled Soldiers by 1931.[5] That doesn’t seem to deter Clifford’s mother, though, as a year before Mr. Wilcox’s hospital admission, and even though Thomas Wilcox isn’t dead at the time of the 1930 census (nor is he living with Grace) – Grace uses the same trick she used with Mr. Dixon in 1920: she lists herself once again as widowed. It’s all good though – because Mr. Wilcox is doing the same thing elsewhere. Can you say irreconcilable differences?

Interestingly, Clifford’s mother Grace uses her married surnames, those of “Dixon” and “Wilcox,” interchangeably or as the occasion might need. In the 1930 Census, she is listed as “the widow” “Grace Dixon,” when in fact she’d been remarried to Thomas Wilcox for eight years. (In 1930 she was in fact neither the widow Dixon nor the widow Wilcox.) She signed her name as “Grace C. Wilcox” on the 1933 and 1934 marriage applications for two of her children. Wait a minute, Grace – so you were listed as the “widow Dixon” in 1920, “Mrs. Grace Wilcox” in 1922, “the widow Grace Dixon” again in 1930, and now you’re “Mrs. Grace C. Wilcox” in 1933 and 1934 – even though Mr. Wilcox isn’t dead? Grace, what the heck is going on?

Regrettably, I am (thus far) unable to verify Grace C. (Reid) (Dixon) Wilcox past this point. However, there are a few last hints of Grace; one is a 1942 Los Angeles voter registration that shows “Mrs. Grace C. Dixon” as an apartment manager in Los Angeles, and another one in 1958 for a “Mrs. Grace C. Dixon,” also in Los Angeles. While I think that this is likely Clifford’s mother, until I can “pinch” myself a death certificate (just kidding) I can’t be sure. This compounded with her flip-flopping last names and the preponderance of “Grace Dixons” and “Grace Wilcoxes” isn’t making the task any easier. Grace likely remarried; she was young enough in 1940 to do so. However, in the very far back recesses of my mind, I remember my grandmother saying that Clifford had had “to leave” (as if to go “into” Los Angeles – a very long trip in 1959), that his mother was very ill or had passed away. This was in the late 1950s, and I’m an old man now in 2021.

Regrettably, I am (thus far) unable to verify Grace C. (Reid) (Dixon) Wilcox past this point. However, there are a few last hints of Grace; one is a 1942 Los Angeles voter registration that shows “Mrs. Grace C. Dixon” as an apartment manager in Los Angeles, and another one in 1958 for a “Mrs. Grace C. Dixon,” also in Los Angeles. While I think that this is likely Clifford’s mother, until I can “pinch” myself a death certificate (just kidding) I can’t be sure. This compounded with her flip-flopping last names and the preponderance of “Grace Dixons” and “Grace Wilcoxes” isn’t making the task any easier. Grace likely remarried; she was young enough in 1940 to do so. However, in the very far back recesses of my mind, I remember my grandmother saying that Clifford had had “to leave” (as if to go “into” Los Angeles – a very long trip in 1959), that his mother was very ill or had passed away. This was in the late 1950s, and I’m an old man now in 2021.

Maybe I just imagined it – anything at all, anything indicating Clifford...

Notes

[1] Clifford Reid Dixon (1912-1985).

[2] Jeff Record, "A place at the table," Vita Brevis, 30 October 2017.

[3] Jeff Record, "White lies," Vita Brevis, 31 May 2017.

[4] Grace C. (Reid) Dixon married Thomas Alvin Wilcox in Los Angeles County on 26 May 1922.

[5] U.S. Homes for Disabled Volunteer Soldiers, 1866-1938, Ancestry.com, shows Thomas was admitted in 1931, suffering from tuberculosis. He lived until 1967; see FindAGrave.com memorial no. 28036140.

Share this:

About Jeff Record

Jeff Record received a B.A. degree in Philosophy from Santa Clara University, and works as a teaching assistant with special needs children at a local school. He recently co-authored with Christopher C. Child, “William and Lydia (Swift) Young of Windham, Connecticut: A John Howland and Richard Warren Line,” for the Mayflower Descendant. Jeff enjoys helping his ancestors complete their unfinished business, and successfully petitioned the Secretary of the Army to overturn a 150 year old dishonorable Civil War discharge. A former Elder with the Mother Lode Colony of Mayflower Descendants in the State of California, Jeff and his wife currently live with their Golden Retriever near California’s Gold Country where he continues to explore, discover, and research family history.View all posts by Jeff Record →