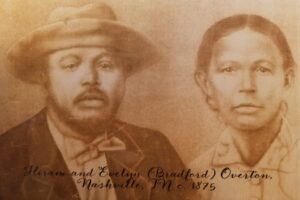

This photograph shows Hiram Overton (ca. 1835-1911) and his wife, Evelyn Overton (1841-1917), my great-great-great-grandparents. We opened Black History Month at Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology with a call to share personal stories highlighting our family connections to the African-American heritage we celebrate for these 28 days. I’m joining in the effort by sharing and honoring the story of Hiram and Evelyn Overton. Together they are the foundations of my maternal lineage, lovers of kin and country, survivors of slavery and institutional racism, keepers of the flame and inspiring #BlackEntrepreneurs.

This photograph shows Hiram Overton (ca. 1835-1911) and his wife, Evelyn Overton (1841-1917), my great-great-great-grandparents. We opened Black History Month at Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology with a call to share personal stories highlighting our family connections to the African-American heritage we celebrate for these 28 days. I’m joining in the effort by sharing and honoring the story of Hiram and Evelyn Overton. Together they are the foundations of my maternal lineage, lovers of kin and country, survivors of slavery and institutional racism, keepers of the flame and inspiring #BlackEntrepreneurs.

Hiram and Evelyn were born into the system of chattel slavery and they miraculously survived with their spirits intact. They labored together on a plantation in Davidson County, Tennessee, in an area of Nashville, my hometown, that is now known as Crieve Hall and encompasses parts of Brentwood. That plantation was called Traveler’s Rest by its founder John Overton, a friend of President Andrew Jackson. The beautiful land on which the plantation sat was land from which the Cherokee Nation was forcibly removed, and it is the earliest known genealogical connection (and location) that my family can trace.

Hiram was a blacksmith and farmer at Traveler’s Rest. As a skilled tradesman he was hired out to multiple plantations and served a valuable role as a technician and all-around fixer. Soon after the Civil War began, Hiram and Evelyn managed to leave Traveler’s Rest, thus emancipating themselves and their young children from the dread of forced and free labor. With his wife and children safe at a nearby farm where they somehow rented land, Hiram left to serve in the Civil War with his brother, shoeing horses and performing other labor in the Union Army encampment in Murfreesboro, Tennessee. Evelyn stayed behind, tending to their young family in dangerous circumstances as a young mother living on rented property, with her husband some 35 miles away.

Soon after the Civil War began, Hiram and Evelyn managed to leave Traveler’s Rest...

After the war, the two continued to rent land, farming and running a blacksmith’s shop that they established on Granny White Pike in the Otter Creek neighborhood. Within two years, the Overtons had amassed enough resources to buy their first property. At the end of their lives their wills indicate that they had accumulated more than 600 acres of prime farmland, expanded and retained ownership of the blacksmith's shop, and become landlords who owned several homes in South Nashville. I have the blessed and unusual privilege of knowing these details about their lives because their granddaughter, Willa Overton (1906-1996), was near and dear to me. She lived with my grandparents later in her life, and I often sat at her knee absorbing oral history, scribbling it down on index cards and in notebooks as an adolescent and a young adult.

I kept this story close to my vest as part of my personal remembrances for a decade. When I moved to Boston in 2005, by happenstance I encountered the resources of the New England Historic Genealogical Society, whose researchers helped me build a robust paper trail that added to the experiential history my family knew to be true. I was grateful to learn through documents, stored at the Library of Congress, that Hiram was interviewed extensively in the early 1900s as part of a restitution claim he made against the federal government for goods and provisions confiscated from his residence during the Civil War. In his affidavit, Hiram testified about his involvement with and loyalty to the Union Army, his reasons for pursuing self-emancipation, and his life in antebellum Nashville after being enslaved. One of the quotes from his interviews stays with me to this day. When asked why he “walked off” the plantation in 1862, Hiram Overton’s simple and poignant response was: “Even birds want to be free.”

I thank them for their sacrifice, their vision, and their tenacity in making a way out of no way. I am because they were. I strive every day to make them proud. Here’s to freedom. For me, #BlackHistory is #MoreThanAMonth.

Share this:

About Aisha Francis

Aisha Francis, Ph.D., is the CEO of the Benjamin Franklin Institute of Technology in Boston. A proponent of access to economic mobility, she is an enthusiastic champion for the learning opportunities her own two children are receiving in Boston's public schools. The daughter of a Dominican Republic immigrant father and mother who is a sixth-generation Nashvillian, she now resides in Boston. Aisha deeply appreciates the fortitude evident in Boston's immigrant and native communities. Her hobbies are reading, cooking, travel, and genealogy.View all posts by Aisha Francis →