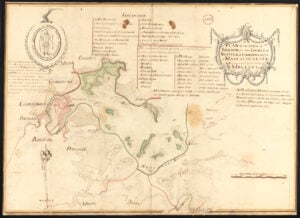

Whenever I find myself doing Massachusetts research that predates 1800, I return to a collection of early town plans, 1794-1795, that are as much a documentary source as they are an aesthetic pleasure. Housed at the Massachusetts State Archives, a division of the Secretary of State, the original collection consists of sixteen volumes which were digitized in June 2017.[1]

In the post-Revolution years, it fell to the individual states to produce accurate maps to facilitate governmental administration, develop transportation networks, and encourage settlement. In Massachusetts, Samuel Adams of Revolutionary War fame was governor when Boston-based surveyor, cartographer, and mathematician Osgood Carleton (1742-1816) developed a proposal, presented to the Massachusetts House of Representatives and enacted by a 1794 Resolve, requiring each town in Massachusetts, including the towns that were then part of Maine, to prepare a town plan based on a survey that was no more than seven years old.[2] The goal was to “facilitate & promote such information and improvements as will be favorable to its [the Commonwealth’s] growth and prosperity.” Chapter 101 specified that the “Selectmen or some other suitable person or persons” be appointed to make accurate plans and that the plans be drawn on a scale of two hundred rods to an inch.[3] Geographical features such as ponds, rivers, and mountains were to be highlighted, but so too were cultural and industrial resources such as manufactories and houses of worship.

The 1795 town plans, mounted on linen, vary in size but are generally in the 12” x 18” range, though several are somewhat larger. The detail varies from a simple outline showing roadways, town boundaries, and prominent natural features to elegant works of art, rich with interior detail, with fine script and watercolor-tints that include compass roses and the location of important town structures such as court houses, windmills, meetinghouses, sawmills, and taverns. Many also include ancillary notes that may prove useful to family historians, often invoking lost names. Dozens of surveyors contributed to the project, many preparing plans for multiple towns. On some plans they have signed their names, though many remain anonymous. Numerous town plans also include the distance from the town to Boston, as well as an affidavit, signed by town fathers, attesting to the completion of the plan.

Dozens of surveyors contributed to the project, many preparing plans for multiple towns.

A couple of Lower Cape projects have had me closely inspecting the town plans of Wellfleet and Truro. Because so much of the 1795 landscape has been lost to and obscured by natural change and modern development, and most, if not all, of the earliest structures that once dominated a townscape are now gone – with few even mentioned in early town histories – the 1795 town plans are useful as confirmation of what was (proof of life, so to speak) and in allowing us to reimagine the geography where our Cape ancestors lived and worked.

For instance, visitors to Wellfleet might wonder why areas along the bay are called Bound Brook Island, Griffin Island, and Great Island when, today, they are not islands but a contiguous land mass. A look at the 1795 town plan shows that the areas were, at one time, separate “islands.” From the historic Duck Creek Cemetery on Route 6, it is difficult today to appreciate the burial ground’s relationship to Duck Creek Harbor, a safe and deep anchorage, where population and industry eventually relocated, but the town plan shows it clearly. It also shows the early meetinghouse, built in 1740, around which the cemetery expanded. Truro’s town plan was equally helpful in showing the location of the long ago demolished early meetinghouse that was situated where the Old North Cemetery spreads out along Route 6. It seems that Provincetown was a bit contrarian in its approach to the town map project, submitting little more than an outline, hardly resembling the town, with notations for only a meetinghouse and two windmills.[4]

The temptation with these town plans, which are alphabetized by the first letter of the town, is that you’ll want to have a look at any that may relate to places of personal interest; thus I examined the plan of my home-town which identifies saw mills, grist mills, the fulling mill, and two early meetinghouses. With Plymouth in the news during this 400th Mayflower anniversary, I had a look at its town plan which, at first glance, appears to be little more than a wide-open space dotted with ponds and bisected by a few roadways. On closer inspection, the tiny village that grew around Leyden Street becomes evident with its mills and forge along the town brook, and its courthouse, wharves, and a scattering of dwellings along the waterfront. An interesting historic notation that has been included on the Plymouth plan recalls Captain Magee’s shipwreck in Plymouth Harbor in December 1778. Stay tuned for a future post about this story!

As one might expect, the town plan of Boston is one of the more exceptional of the maps...

As one might expect, the town plan of Boston is one of the more exceptional of the maps, richly detailed and elegantly designed with the state seal depicted and neighboring communities as well as the Boston Harbor Islands identified. An “explanation” key offers some fascinating insight into the times, one notation showing the land upon which “the new state house is building.”[5] The smallness of the plan’s scale, explains the key, “prevents pointing out the exact location of the following objects,” but it enumerates, among many other establishments, 18 houses of public worship, six public schools, 12 rope walks, 32 distilleries, five sugar refineries, one chocolate mill, three banks, and one glue, two spermaceti, and six tallow manufactories.

Boston’s surveyor is identified as New Hampshire-born Osgood Carleton, the inspiration behind the town plan project. Though without formal schooling, Carleton’s mathematical aptitude suggests a period of apprenticeship, perhaps with John Henry Bastide, the chief engineer at the Siege of Louisbourg (1758). At the age of sixteen, Carleton had served with New England troops at Louisbourg during the Seven Years War, later serving as an officer during the Revolutionary War, after which he launched his career as a “Teacher of the Mathematicks” in Boston. Among his many cartographic projects, the most ambitious was the collection of town surveys that were printed – after numerous delays – in 1802, now available so that we can understand the world as it was. [6]

Notes

[1] digitalarchives.sec.state.ma.us.

[2] Massachusetts General Court, Resolves, 1794, May Session, ch. 101. Town plans were also compiled in 1830 and these, too, are digitized (2018).

[3] A rod is an old English measure equal to 16.5 feet or 5.5 yards.

[4] The 1830 Provincetown plan makes up for the 1795 deficits, with considerable information and design.

[5] Designed by architect Charles Bulfinch, ground was broken on 4 July 1795; work was completed in January 1798.

[6] For a fuller appreciation of the life and work of Osgood Carleton, see David Bosse, “Osgood Carleton, Mathematical Practitioner of Boston,” Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 107 [1995]: 141-64, available at jstor.

Share this:

About Amy Whorf McGuiggan

Amy Whorf McGuiggan recently published Finding Emma: My Search For the Family My Grandfather Never Knew; she is also the author of My Provincetown: Memories of a Cape Cod Childhood; Christmas in New England; and Take Me Out to the Ball Game: The Story of the Sensational Baseball Song. Past projects have included curating, researching, and writing the exhibition Forgotten Port: Provincetown’s Whaling Heritage (for the Pilgrim Monument and Provincetown Museum) and Albert Edel: Moments in Time, Pictures of Place (for the Provincetown Art Association and Museum).View all posts by Amy Whorf McGuiggan →