Like so many passionate genealogists, I descend from proud and feisty Irish famine immigrants. While the details of how my great-great-grandfather Thomas Healy made his way to the United States have not come down to us, his life here and in Ireland became clearer thanks to a tremendous amount of research time, more than a little bit of luck, and some rather unique research tools.

Like so many passionate genealogists, I descend from proud and feisty Irish famine immigrants. While the details of how my great-great-grandfather Thomas Healy made his way to the United States have not come down to us, his life here and in Ireland became clearer thanks to a tremendous amount of research time, more than a little bit of luck, and some rather unique research tools.

Thomas married Ann Knight at St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Hudson, New York in 1854. Together, they worked hard, and through thrift and ingenuity purchased 40 acres of land in the neighboring town of Greenport by 1866 ... land that their descendants remained on, and added to, for more than 100 years.

Knowing the painful struggles of Irish famine immigrants only adds to my immense pride and awe at what Thomas and Ann accomplished. The land that they purchased is land that my great-grandfather, grandfather, and father grew up on. It was part of their fiber, their souls, and made them who they were and are today. We have pictures of the farm at its most prosperous from the 1950s, newspaper articles from when the farm burned in the 1940s, pictures of life on the farm from the 1930s, and of the farm house itself from the 1920s. We have a copy of each deed for the land that was purchased and added to the original forty acres between 1866 and 1950. This is the texture genealogical research seeks. This detail is what allows us to get to know the lives of our ancestors better.

The land that they purchased is land that my great-grandfather, grandfather, and father grew up on. It was part of their fiber, their souls, and made them who they were and are today.

But what did Thomas leave behind in Ireland and what was his life like there? Answers to those questions are the point of genealogical research, after all. We want to know more than just names and dates. We want to know what it was like to be them in their time, to find the details of their struggles, their triumphs, and what made them who they were, and ultimately who we are today.

How do we collect this information on our Irish famine immigrants in the absence of the records lost to the Public Records Office fire in 1922? The answers are not simple, nor are the steps we must take to solve them. It takes a tremendous amount of luck, a lot of time, and some unique tools to get there.

First, let’s start with luck, because I’ve had a bit of it.

Anyone who researches Irish surnames knows the tremendous challenges that come with names like Murphy, Kelly, Sullivan, Walsh, or Smith. But my family name, Healy, is ranked #48 out of a list of 100 most common Irish surnames, and this factor helped.

Living with Thomas was Maurice Healy, 65 years old, father of the head of the household.

Additionally, New York conducted a state census in 1855, and it was in this census for the town of Hudson, and in the household of 28-year-old Thomas Healy, the one-and-only Thomas Healy in the area at that time, that I was able to take my family back one more generation. Living with Thomas was Maurice Healy, 65 years old, father of the head of the household.

Next, Thomas gave me the wonderful gift of stating on his 1860 declaration of intent to naturalize that he was not only born in Ireland (as many petitions stated during this time period), but that he was born in Kilkenny. Now that I knew Thomas was from Kilkenny, I also knew that Maurice had once lived there. It is this gateway information that helped me locate some of the details of their life in Ireland.

Anyone who has researched ancestors in Ireland in the early nineteenth century is familiar with Griffth’s Valuation, a property tax survey which created a value for land and buildings through an analysis of the factors that contributed to the economic position of a property. Using the search function and putting in these unique details (Maurice Healy, County Kilkenny), I was able to locate the Healys’ townland because, thanks to some good luck, there was only ONE Maurice Healy enumerated in the Griffith’s Valuation Field Books in County Kilkenny!

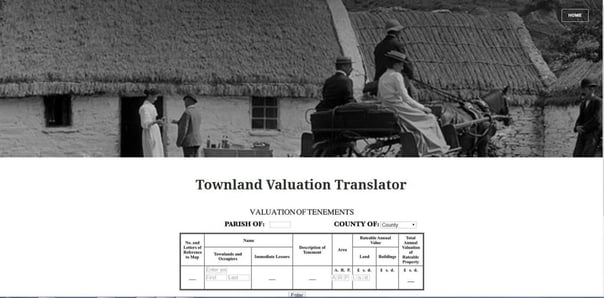

Griffith’s Valuation offers interesting yet somewhat confusing and meaningless information. (Am I alone in not knowing how 15 acres, 3 rods, 18 perches of land with a total net annual value of 7 pounds translates to their quality of life?) But thanks to the information in Griffith’s Valuation I knew that Maurice lived in the parish of Sheffin, in the county of Kilkenny, and had 15 acres, 3 rods, and 18 perches of land valued at 6 pounds, 3 shillings, I was able to input these facts into a unique tool called the Townland Valuation Translator, created by John Schnelle.

Griffith’s Valuation offers interesting yet somewhat confusing and meaningless information. (Am I alone in not knowing how 15 acres, 3 rods, 18 perches of land with a total net annual value of 7 pounds translates to their quality of life?) But thanks to the information in Griffith’s Valuation I knew that Maurice lived in the parish of Sheffin, in the county of Kilkenny, and had 15 acres, 3 rods, and 18 perches of land valued at 6 pounds, 3 shillings, I was able to input these facts into a unique tool called the Townland Valuation Translator, created by John Schnelle.

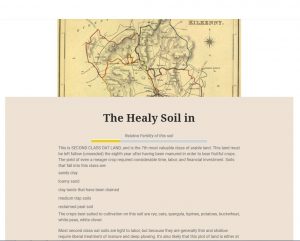

The Translator takes that information and paints a detailed picture of the ancestor’s existence on this land. Through the Translator I learned that Maurice Healy was considered a “family farmer,” which meant that every operation of the farm could be completed by members of the family. The family farmer was in the top 14.7% of the adult males, yet still part of the rural poor society.

Maurice and Thomas likely lived in a single-story cottage which they built themselves. The cottage would have been made of clay bricks that had been white-washed in limestone and water, both inside and out. The roof was thatched and there would have been a center hearth and chimney.

The land would have been shallow and thin, requiring liberal amounts of manure and deep plowing...

The land would have been shallow and thin, requiring liberal amounts of manure and deep plowing to yield a meager crop that required a considerable amount of time, labor, and investment. This land would have been suitable to grow various crops, but most likely rye, oats, potatoes, or buckwheat.

Maurice and Thomas each would have needed to eat approximately 12–14 pounds of potatoes each day to consume enough calories to farm this land, and Maurice’s wife Mary would have required about 9 pounds.

Fascinating!

The details presented through the Townland Valuation Translator are engrossing. They add texture and depth to the lives of the Irish people in the first half of the nineteenth century and help genealogists to weave the details of their ancestors’ lives together, painting a more complex and colorful picture of life 170 years ago.

Share this:

About Tricia Mitchell

Tricia Healy Mitchell is a genealogist at the New England Historic Genealogical Society and a graduate of the Boston University Certificate program in Genealogical Research. Her areas of experience and research interests include New York, Maine, Massachusetts, and Ireland. She authored the Portable Genealogist: Probate Records and she is a member of the team offering lectures and webinars at the American Ancestors Research Center and at AmericanAncestors.org. She holds a Bachelor of Science degree in business from the University of Maine.View all posts by Tricia Mitchell →