[Editor's note: This blog post originally appeared in Vita Brevis on 22 April 2016.]

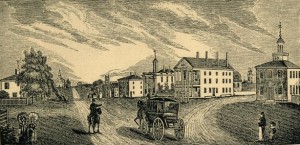

Engraving of the town of Lenox, Massachusetts, by John Warner Barber. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Engraving of the town of Lenox, Massachusetts, by John Warner Barber. Image courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

Genealogists and historians of Massachusetts are indebted to the works of nineteenth-century antiquarians: that is, compilers or collectors of historical information and antiquities. The works of several antiquarians – including John Warner Barber, Samuel Gardner Drake, and John Haven Dexter – have become crucial reference works in the study of Massachusetts genealogy. Knowing what these sources contain, along with their respective shortcomings, can be helpful when researching your Massachusetts ancestors.

John Warner Barber (1798–1885), a native of Connecticut, published his sizable History and Antiquities of Every Town in Massachusetts in 1839. The work provided historical sketches of every Massachusetts town in existence at the time of the text’s printing, along with a plethora of woodcut illustrations created by Barber himself. These illustrations are important in and of themselves, as they frequently allow the reader to become acquainted with the historical landscape and geography of a particular town. The accuracy of these images, we can assume, is quite good. Barber explains in the preface to his book that the majority of these engravings were “taken on the spot.”[1]

One should be aware ... that Barber – like many nineteenth-century authors – did not cite all of his sources.

The text is very helpful to the genealogist, as each sketch typically provides the year of a town’s incorporation, information pertaining to a town’s buildings and ecclesiastical history, and lists early town settlers. I have found the latter category of information to be particularly helpful in my own genealogical research. One should be aware, however, that Barber – like many nineteenth-century authors – did not cite all of his sources. The sketches, moreover, are not all equal in length or detail. For example, Barber limits his treatment of the town of Dunstable to six sentences, while his discussion of the town of Hopkinton spans about 5 pages.[2]

Samuel G. Drake (1798–1875) and John H. Dexter (1791–1876) both compiled information pertaining to the history of Boston. Drake, a native of New Hampshire, published his History and Antiquities of Boston in 1856. While the text provides an important history of the town of Boston (spanning 1630–1770), the book also contains several elements of interest to genealogists. The text, for one, contains pedigree charts for several of Boston’s more prominent citizens.[3] Of additional interest are the appendixes to the text. Appendix One contains a transcription of the earliest book of possessions of the Town of Boston.[4] Appendix Two also contains a lengthy list of “Ancient Objects and Localities” – a list to which I have frequently referred while performing research in Boston.[5] The list records street name changes, along with the names of buildings that were no longer in existence in the city.

John Haven Dexter, a native of Massachusetts, was less an historian of Massachusetts and more a recorder – as Ann Smith Lainhart and Robert J. Dunkle note – of “facts about persons and localities in Boston.”[6] Dexter’s voluminous collection of notes on seventeenth- and eighteenth-century Bostonians not only contain important vital statistical information, such as births, marriages, and deaths, but also interesting biographical information and quick genealogical sketches.

John Haven Dexter [was a recorder] of “facts about persons and localities in Boston.”

For example, an entry for John Greenleaf not only records his father’s name, but the parents of his wife, Lucy Cranch. The same entry also makes note of John Greenleaf’s son, Daniel, along with Daniel’s wife.[7] Dexter’s notes survive today in the manuscripts collection at NEHGS, and are also available in printed form and as a searchable database at AmericanAncestors.org. Lainhart and Dunkle caution, however, that Dexter’s work “has not been verified in every case,” and that Dexter occasionally relied on secondary sources, such as newspapers, when composing some of his notes.[8]

All things considered, the works of Barber, Drake, and Dexter, can serve as helpful guides when performing genealogical research, but should always be checked – where possible – against primary sources. Researchers will benefit from the historical information contained in Barber’s, Drake’s, and Dexter’s works, which will help to provide much-needed context for the lives of Massachusetts’ early residents.

Notes

[1] John Warner Barber, preface to History and Antiquities of Every Town in Massachusetts (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2014), iv.

[2] Barber, History and Antiquities of Every Town in Massachusetts, 387, 393-97.

[3] Samuel G. Drake, The History and Antiquities of Boston from its Settlement in 1630, to the Year 1770 (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 2013), 68, 72, 227, 293, 363.

[4] Ibid., 785-801.

[5] Ibid., 802-19.

[6] Robert J. Dunkle and Ann Smith Lainhart, introduction to John Haven Dexter’s Memoranda of the Town of Boston in the 18th & 19th Centuries (Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society, 1997), i.

[7] Dunkle and Lainhart, John Haven Dexter’s Memoranda, 233.

[8] Dunkle and Lainhart, introduction to John Haven Dexter’s Memoranda, ii.

Share this:

About Dan Sousa

Dan Sousa currently serves as the Decorative Arts Trust Curatorial Intern at Historic Deerfield, Inc.—a museum in Deerfield, Massachusetts—where he is involved in several research, exhibition, and publication projects. His research interests include early American history and material culture, Massachusetts history and genealogy, Boston history and genealogy, and the history of American Catholicism. He holds a B.A. in history from Providence College and an M.A. in history from the University of Massachusetts, Boston.View all posts by Dan Sousa →