While searching for online records for Bremen, Germany, I came across a digitized collection of Bremen address books spanning the period 1794–1955 with the help of the website German Roots. The Bremer Adressbücher 1794-1955 (Bremen Address Directories) database has been digitized by the State and University Library of Bremen, and can provide a wealth of information about your Bremen ancestors that might not be found in American records.

While searching for online records for Bremen, Germany, I came across a digitized collection of Bremen address books spanning the period 1794–1955 with the help of the website German Roots. The Bremer Adressbücher 1794-1955 (Bremen Address Directories) database has been digitized by the State and University Library of Bremen, and can provide a wealth of information about your Bremen ancestors that might not be found in American records.

These directories can be browsed by surname and street number, like the city directories published for Massachusetts. The website and the directories are both in German, but you can use the Google page translator function on your browser or simply open a second tab to Google Translate for words that you need help deciphering. Once you begin attempting to translate the actual record, it can be helpful to keep handy a chart of German letters and common abbreviations such as the one at left.[1]

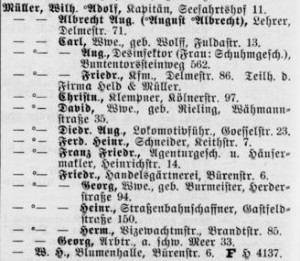

As an example, I searched the 1920 directory under the section “Einwohner,” which corresponds to surname or person, for the relatively common name “Muller.”[2] The directory is organized with the surname first in bold followed by the given names. This is an excellent method to differentiate between individuals with similar names, especially as Germans would often have multiple given names.

In the example you can see that the first individual would have been named Wilhelm Adolph Muller and the second Wilhelm Albrecht August Muller, as the first name, Wilhelm, is carried down the line. Following the bolded names are an occupation and a street address. If you already know the address of your ancestor from an immigration or other record, you can perform a reverse search by street name and number in the address book’s second section, or you can use the address to narrow down the possibilities. Keep in mind as well that the street names are often abbreviated: for example “Brandtstr. 85,” the address of Wilhelm Friedrich Herman Muller, would read as 85 Brandtstrasse or Brandt Street.

In the example you can see that the first individual would have been named Wilhelm Adolph Muller and the second Wilhelm Albrecht August Muller, as the first name, Wilhelm, is carried down the line. Following the bolded names are an occupation and a street address. If you already know the address of your ancestor from an immigration or other record, you can perform a reverse search by street name and number in the address book’s second section, or you can use the address to narrow down the possibilities. Keep in mind as well that the street names are often abbreviated: for example “Brandtstr. 85,” the address of Wilhelm Friedrich Herman Muller, would read as 85 Brandtstrasse or Brandt Street.

Regarding the occupation designation, you will need your translation tools. Line two reads: “Muller, Wilhelm Albrecht Aug. (August Albrecht), Lehrer, Delmestr. 71.” Wilhelm Albrecht/August Muller’s occupation would have been “Lehrer” or teacher.

Another helpful designation included in these addresses concerns widows and female heads of household. Referring to the entry for Wilhelm Friedrich George Muller, we see the designation “Wive., geb.” This is meant to designate this person as the widow of Wilhelm Friedrich George Muller; her maiden name (“geb.”) would be Burmeister. So we can learn from this record that Wilhelm Friedrich George Muller died before 1920 and that his wife’s maiden name was Burmeister.

Whether you are an experienced genealogist or a relative newcomer to the pursuit, the impasse sometimes represented by emigration can be a challenge to family historians of all skill levels. The digitization of passenger lists and naturalization records has provided countless seekers with information such as birth date, place of origin, and even the names of family members.

But what do you do when those clues lead you into genealogical territory in a country with which you are unfamiliar or whose language you do not comprehend? Simply locating records that might be useful, let alone digesting and analyzing their data, can be enough to construct a brick wall in the path of even the most fervent family historian. But with some creativity and a few handy tricks, you might find you are able to extend your research past the records of the United States and learn a little something of your family's global origins.

Notes

[1] “Handwriting Guide: German Gothic,” Family History Library, http://feefhs.org/guides/German_Gothic.pdf.

[2] Bremen Adressbuch, 1920 (Bremen: Schünemann, 1794 - 2002), II: 454. Accessed through Breme : Staats- und Universitätsbibliothek, 2014 – 2013: http://brema.suub.uni-bremen.de/periodical/pageview/719272.

Share this:

About Anna Todd

Anna holds a Master’s degree in history from the University of Connecticut where she specialized in gender and law in colonial New England. She completed her Bachelor’s degree in history with a minor in English at the University of Southern Mississippi. Prior to joining the research services staff at NEHGS she worked as a page at the Thomas J. Dodd Research Center at the University of Connecticut and volunteered with the McCain Library and Archives at the University of Southern Mississippi, the Mississippi Department of Archives and History, the Eudora Welty House, and the National History Day Organization. Her interests include colonial America, New England, Pennsylvania, and the South, and she enjoys infusing family histories with interesting information found in court records, wills, city directories, and other supplementary sources.View all posts by Anna Todd →