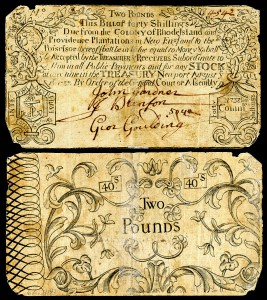

£2 Colonial currency from the Colony of Rhode Island. National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution.

£2 Colonial currency from the Colony of Rhode Island. National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian Institution.

Prior to the Coinage Act of 1792, which established the dollar, the English pound was the primary form of currency in colonial America. The pound—which, in the Middle Ages, was valued the same as one pound of sterling silver—had 20 shillings, and each shilling had 12 pence (pennies).[1] (The modern pound follows the decimal system and, since 1971, has been divided into 100 pence.)

Family historians reading about English or colonial money will see the symbol £ for pounds, and the abbreviation s for shillings and d for pence. All derive from the Latin: £ resembling an L for libra, a Roman unit of weight; and the d and the s for denarius and solidus, Roman coins.[2] Sometimes a specific amount was written with those abbreviations, and sometimes a period was used to delineate each unit of currency: for example, £27 19s 6d or £27.19.06.

In addition to pounds (also called “sovereigns”), shillings (“bob”), and pence, when reading historic documents you’ll see reference to other coins, including the half-sovereign (10 shillings); crown (5 shillings); half-crown (2s 6d); sixpence (“tanner”); threepence (“thruppence”); twopence (“tuppence”); half penny (“ha’penny”); and farthing (quarter penny).

What were colonial currencies worth in today’s terms? Professor John J. McCusker has written, “£750 in Massachusetts during 1750 is worth roughly $48,000 in 2000,”[3] acknowledging that this figure is an approximation. In fact, historians do not agree on a basic formula to determine the current value of colonial American currency, owing to a lack of complete economic data, the fluctuating value of imported goods, and the fact that each colony—while following the English system—had its own currency. Further, a colony didn’t produce its own coinage, using instead existing coins in circulation, from the Netherlands, Spain, German states, and other countries.[4] As a result, many coins were valued differently from colony to colony.

And so what are we to think when we read, in an estate inventory, that a blue coat, jacket, and breeches were valued at £1 19s; a bed and bedding at £3 pounds 15s; 9 tons of English hay at £21 12s; and three fat swine at £5 6s 8d?[5] The best we can often do is look at the relative worth of items—and yet even that can be unreliable because some of the items might be imports, which would have been assigned a higher value. Thus we can see why Professor Ronald Michener says, “The differences between today and then are too great to make a comparison. Viewed from the twenty-first century, life in colonial America was like living on a different planet.”[6]

Notes

[1] David Walbert, “The Value of Money in Colonial America,” North Carolina Digital History, www.learnnc.org/lp/editions/nchist-colonial/1646.

[2] Ibid.

[3] John J. McCusker, How Much Is That in Real Money? A Historical Price Index for Use as a Deflator of Money Values in the Economy of the United States (Worcester, Mass.: American Antiquarian Society, 2001), cited in Ed Crews, “How Much Is That in Today’s Money?” Colonial Williamsburg Journal, vol. 2, http://www.history.org/foundation/journal/summer02/money2.cfm.

[4] Jordan Louis, “The Comparative Value of Money between Britain and the Colonies,” University of Notre Dame Department of Special Collections, available at http://www.coins.nd.edu/ColCurrency/CurrencyIntros/IntroValue.html.

[5] Estate of Daniel Austin, Essex County Probate Records, online database at AmericanAncestors.org, Case no. 1011.

[6] Cited in Crews, “How Much Is That in Today’s Money?”

Share this:

About Zachary Garceau

Zachary J. Garceau is a former researcher at the New England Historic Genealogical Society. He joined the research staff after receiving a Master's degree in Historical Studies with a concentration in Public History from the University of Maryland-Baltimore County and a B.A. in history from the University of Rhode Island. He was a member of the Research Services team from 2014 to 2018, and now works as a technical writer. Zachary also works as a freelance writer, specializing in Rhode Island history, sports history, and French Canadian genealogy.View all posts by Zachary Garceau →